No one in Cleveland or Akron or Ashtabula complains to or congratulates Connecticut Governor Dannel Malloy. No one in Warren, Medina or Sandusky cares if U.S. Senator Chris Murphy should be re-elected in 2018. There is no sharing of state offices between Cleveland and Hartford and thus, only one direct flight between Cleveland Hopkins and Hartford Bradley. And we sure don’t call ourselves the Nutmeg State, or even the exclave of same.

Perhaps we should have been. For more than 200 years, people living in cities like Cleveland, Akron, Ashtabula, Warren, northern Youngstown, Medina, Lorain, Elyria, Norwalk, Sandusky and Put-In-Bay have lived in the state of Ohio. What if Connecticut relinquished these lands, called the Connecticut Western Reserve or New Connecticut without following proper procedure?

There is no question that Northeast Ohio is different from the rest of the Ohio. Its politics are more liberal. It’s more urban. Its culture is faster-paced than the rest of Ohio. Its architecture is different, with old and modern buildings alike copying the white-trimmed, brick, colonial structures 400 miles farther east.

“If you drive through the area of Ohio still called the Western Reserve today, you will find towns named Norwich, Saybrook, New London, Litchfield, Mansfield, and Plymouth,”?wrote Barbara Austen, the Florence S. Marcy Crofut Archivist at the Connecticut Historical Society. “Many of these communities have a town green or square and the ubiquitous white-steepled church common to Connecticut.”

There is also no question that Connecticut removed all public governance over this 3,366,921 acres (5,280 square miles) in 1795 without a vote by the citizens of its state — including in the Western Reserve. This?great expanse of land was left in limbo, perhaps illegally. Connecticut’s haste in ridding itself of its Western Reserve was due to its desperate need of money.

In 1787, four years after the Revolutionary War officially ended, states began entering the United States of America. But some eastern states originally were much larger than they are today. For example, Georgia (entered USA in 1788), Virginia (1788) and North Carolina (1789) extended west all the way to the Mississippi River. New states were carved from their western expanses, including Kentucky (1792), Tennessee (1796),?Mississippi (1817),?Alabama (1819) and West Virginia (1863). All of the eastern states handed over governance of their western lands either to another, new state or to the federal government and they did so either by a vote of the state legislature, Congress, the people in the western lands — or all three.

Connecticut was the exception. As a British colony, its land rights included a 70-mile-wide strip north of latitude 41 across what is now northern Pennsylvania, northern Ohio and beyond. This 1662 Charter of Conveyance by King Charles II theoretically extended across uncharted lands to the Pacific Ocean. It was considered a “sea to sea” charter. This document, called the Charter Oak, was deemed to be so valuable that it was hidden in 1685 inside a 1,000-year-old white oak tree in Hartford during a fierce dispute with King James II over the revocation of royal charters that allowed the colonies to govern themselves. Its value didn’t last.

Two years before it entered the USA as a state on Jan. 9, 1788, Connecticut gave up all of its western land to the federal government in exchange for wiping its Revolutionary War debts clean. But it didn’t give up its Western Reserve. Connecticut?s claim to all other western lands was ceded to the Unites States by a deed dated September 13, 1786 and signed for the state by its delegates in Congress.

This instrument conveyed to the United States:?“All right, title, interest, jurisdiction and claim which the said State of Connecticut hath in and to certain western lands (all lands lying west of a line beginning at the completion of the forty-first degree of north latitude, 120 miles west of the western boundary of Pennsylvania and from thence by a line drawn north parallel to and 120 miles west of the said west line of Pennsylvania and to continue north until it comes to 42o 02′ north latitude.)”?

So when Old Connecticut became a state, so did the Western Reserve, also known as New Connecticut. The Western Reserve enjoyed sovereign jurisdiction, including legal and military protections, as part of the state of Connecticut. It was also granted those by its new nation. The frontier wilderness that today is heavily urbanized by 3.3 million people was a part of the state of Connecticut for seven years.

How did it cease being a state? At best, ambiguously. At worst, illegally.

The reason, as one might expect, was due to money. Like other former colonies, Connecticut relinquished its western claims (except the Western Reserve) to the federal government to wipe clean its debt from the Revolutionary War. Connecticut also needed cash to rebuild after the war.

The British had burned many of Connecticut’s cities and towns and, with them, its schools and universities. If this fledgling state was going to survive and grow again, it needed an educated populace. So it sold for $1.2 million the eastern 2.867 million acres of the Western Reserve to the Connecticut Land Company, newly formed by 35 investors. The western portion remained with Connecticut and, after 1792, was offered to suffering citizens who were burned out of their homes and businesses by the British. That western portion, measuring 500,000 acres, was appropriately named The Firelands.

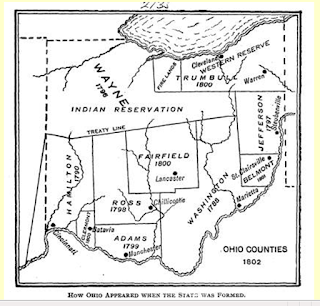

By selling the Western Reserve to the Connecticut Land Co. in 1795, Connecticut ceased to govern the land. It was no longer a state. No one else governed it either. Most of it wasn’t even Indian land as the Treaty of Greenville extinguished Indian rights to land east of the Cuyahoga River in 1795. The land remained in limbo until 1800 when the federal government absorbed the former Western Reserve into the Northwest Territory which had covered the rest of the Ohio Country as well as today’s Indiana, Illinois, Michigan, Wisconsin and part of Minnesota since 1787.

Connecticut did not amend its state Constitution or pass any statutes to cede the Western Reserve. It relinquished governance of this area, larger than Connecticut and Rhode Island combined, by deed.

“The (Connecticut Land) company issued to the state of Connecticut a mortgage on the land as security for the purchase price. From time to time as payments were made on this obligation, the state gave its deed of release and discharged the mortgage. Copies of such deeds are still on hand in the Recorder’s office in Cleveland,” according to the Web site of the Cuyahoga County Fiscal Officer.

No legal documents mentioned inclusion of the Western Reserve in the Northwest Territory until a year after Connecticut sold it, according to The Corporate Birth and Growth of the City of Cleveland: An Address to the Early Settlers’ Association of Cleveland, Delivered July 22nd, 1884 by S.O. Griswold.

Settlers were reluctant to purchase Connecticut Land Co. properties because the title to the land and the right to govern it were unclear, according to Case Western Reserve University historical records. Settlers did not recognize the authority of the governor of the Northwest Territory while Connecticut refused company pleas that the state exercise the territorial rights it had already ceded.

This “ambiguity” lasted until 1800 when Congress passed the Quieting Act. In it, the U.S. restored Connecticut’s claim to the Western Reserve so that the company’s land titles would be quieted and guaranteed. Connecticut then granted the U.S. jurisdiction over the Western Reserve on July 10, 1800. The Western Reserve became a sprawling Trumbull County, seated at Warren, and a part of the Northwest Territory.?

But the Western Reserve was in fact a state or, more accurately, part of a state. Its cessation as a state and reversion to territorial status was done without a popular vote. It’s true that the Constitution gives Congress power to determine the process for creating states out of lands that were U.S. territories.

“The Congress shall have power to dispose of and make all needful Rules and Regulations respecting the Territory or other Property belonging to the United States?” ? U.S. Constitution, Article IV, Section 3, clause 2.

The Constitution and federal statutes are silent on how a region loses its status as a state.

“As far as I can tell, the only way that a state can cease to exist is for that state to adopt, according to its own law, a binding resolution that it has ceased to exist,” wrote Forbes journalist Kelly Kinkade at quote.com. “As far as I know, this would require the State to adopt an amendment to its Constitution, as no State has any provision for declaring its own dissolution within its present Constitution.”

So, logic suggests that for a region to lose statehood, it would have to undergo the same process of territories seeking statehood — only in reverse. Historically, Congress has applied the following general procedure when granting territories statehood:

- The territory holds a referendum vote to determine the people’s desire for or against statehood.

- Should a majority vote to seek statehood, the territory petitions the U.S. Congress for statehood.

- The territory, if it has not already done so, is required to adopt a form of government and constitution that are in compliance with the U.S. Constitution.

- The U.S. Congress ? both House and Senate ? pass, by a simple majority vote, a joint resolution accepting the territory as a state.

- The President of the United States signs the joint resolution and the territory is acknowledged as a U.S. state.

The Western Reserve was absorbed into the state of Ohio in 1803 and the Connecticut Land Co. was finally dissolved in 1809 as a financial failure. But is Connecticut’s cessation of governance what the citizens and investors of the Western Reserve wanted?

One could argue that, following successful litigation, the former lands of the Connecticut Western Reserve should revert to the governance of its eastern counterpart so that it could be properly ceded to an interested governing authority. If no popular vote is taken, the Western Reserve should remain a part of Connecticut until people in the enclave of Connecticut and in the exclave of the Western Reserve both say otherwise. Or, perhaps a vote should be taken in both old and new Connecticut to determine the wishes of its electorate?

The key here is “an interested governing authority.” Earlier this year, the Cleveland Plain Dealer argued in a series of articles, driven in part by humor but also by serious concern, that red-state Ohio is disinterested in providing governmental services and investment in the more liberal, urbanized lands of the Western Reserve. The PD postulated what the Western Reserve would look like as a separate state.

But no additional state is necessary if the ambiguities if not illegalities outlined in this blog means that the Western Reserve should revert to Connecticut. It would become part of Connecticut again and governed by its Governor, state legislature (without gerrymandering) and two U.S. Senators. Our Congresspersons would likely remain, but again without all of the Republican gerrymandering to divide up and weaken Democratic constituencies.

Might Connecticut be interested in having the Western Reserve back? Possibly, since it would nearly double the state’s population and give it a larger Congressional voting block with at least three more Congresspersons. But it would be a bit difficult to govern since the Western Reserve and Connecticut are separated by two states and 400 miles. Then again, these aren’t the early days of the Republic when small states were favored to make access by horse-power to state capitals easier. One can fly back and forth between the Western Reserve and Connecticut at 500 mph.

The Western Reserve might also be interested in having Connecticut govern it again. After years of losing population, Connecticut is engaged in an aggressive urban redevelopment strategy to attract creative young people, boost investment in older urban cores, as well as revitalize public transportation to improve job access for all. These are all things that Ohio is neglecting in its governance of the urbanized Western Reserve.

The Quieting Act probably resolved the fate of the Western Reserve to the satisfaction of Congress. But shouldn’t a state’s citizens have the right to vote on whether it will no longer be a state? If not, who wants to file a lawsuit to test this theory?

__________________

APPENDIX

Here are the 14 Ohio counties (or parts thereof) which are part of the former Western Reserve and their 2016 populations:

Ashland (northern 1/6th) -?8,942

Cuyahoga -?1,249,352

Erie -?75,107

Geauga -?94,060?

Huron -?58,439

Lake -?228,614

Lorain?- 306,365

Mahoning (northern half) – 130,004

Medina – 177,221

Ottawa (eastern 1/6th – 6,773

Portage – 161,921

Summit – (northern 5/6th) 535,798

Trumbull – 201,825

———

3,332,652 TOTAL WESTERN RESERVE 2016

END