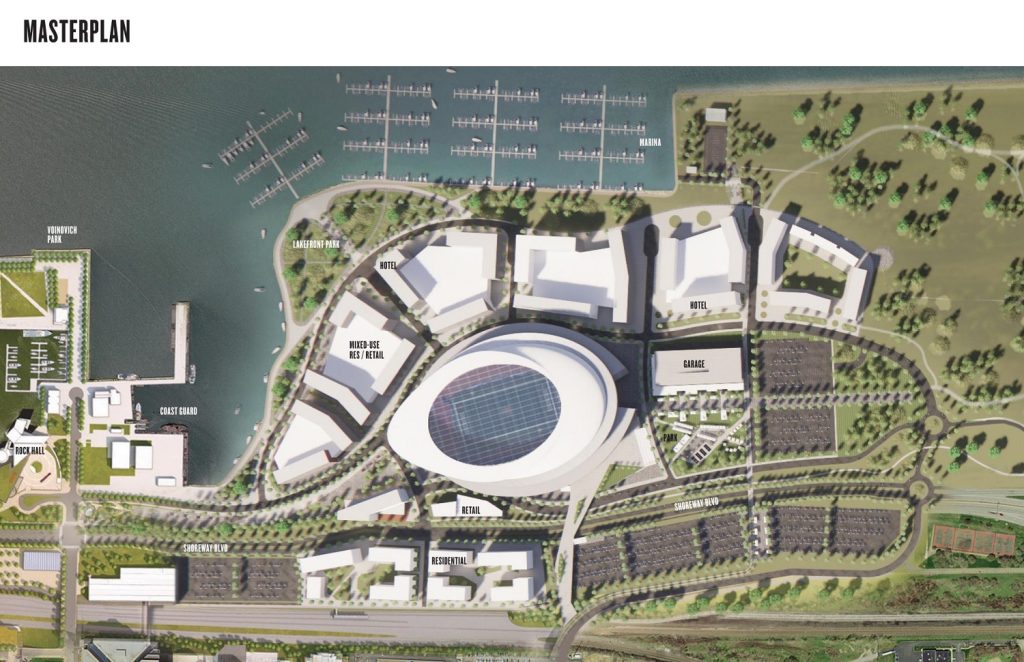

An unofficial, conceptual rendering of what Downtown’s Cleveland lakefront immediately north of the central business district could look like if Huntington Bank Field were replaced by smaller, productive, everyday uses — and if Burke Lakefront Airport was closed and replaced by other uses, including possibly a relocated, all-purpose domed stadium that pushed land-eating parking away from downtown (Ardoonave). CLICK IMAGES TO ENLARGE THEM.

Stadium is an opportunity cost for downtown

A COMMENTARY

One of the most anticipated games in my early Cleveland Browns fandom came three days after Thanksgiving in 1979. The 8-4 Browns faced the hated Steelers at Three Rivers Stadium in Pittsburgh where the Browns had yet to win. The Steelers were going for their fourth Super Bowl in the 1970s and the Browns were trying to get back to their glories of the prior three decades.

Even though the Browns lost that game 33-30 in overtime, the 12-year-old version of me was hooked. Previously, I watched the Browns on television only when other family members tuned in first. After that overtime thriller, I sought out the remaining games that season. Then the excitement of the 1980 season of the Brian Sipe-led Kardiac Kids meant there would be no turning back for me. I became a Browns fan for life.

But I am also an urbanist. Less than a decade later, I learned in Kent State University urban geography courses what makes a city. A 60,000-plus-seat football stadium isn’t one of them. It’s no wonder that just half of the 32 National Football League teams play their home games in downtown stadiums. Cleveland should let the Browns — and especially its parking — leave the heart of downtown.

Why? Because the cost of the Browns’ venue far exceeds the benefits of said venue. And the loss of the Browns can easily be made up by redeveloping Cleveland’s precious lakefront land with multiple, less monolithic mixed uses that can produce more value in dribs and drabs on a daily basis year-round.

All of this follows the news NEOtrans broke in February, that the Haslam Sports Group, owners of the Cleveland Browns, have a purchase agreement to buy 176 acres in the Cleveland suburb of Brook Park. There, they plan to build a $2.4 billion roofed stadium and another $1.2 billion in supportive development. Half of the cost of the new stadium would be financed by public sources, the Haslams hope.

Huntington Bank Field, home of the Cleveland Browns, is a land hog that represents a large opportunity cost for Downtown Cleveland. All downtowns thrive on density, thousands of everyday events and walkability, and a demanding football stadium detracts from these (Google).

That doesn’t include the cost of the events themselves. At a June Brook Park City Council meeting, Mayor Edward Orcutt reported that he had met with his counterpart at Orchard Park, NY. Mayor Jo Ann Litwin Clinton told Orcutt that the Buffalo suburb loses about $200,000 per year in safety forces overtime and other costs to have the Buffalo Bills stadium there.

Same situation at Foxboro, MA, where its mayor told Brook Park’s they’re on the short end of a net fiscal impact from the New England Patriots’ football stadium. Yet Orcutt is excited about the prestige such a stadium would bring to his suburb. Public relations is about the biggest benefit a city can have from hosting pro football games. That’s often difficult to quantify.

Cleveland Mayor Justin Bibb tried to measure all of the benefits, however. He lamented in a recent press statement that the Browns leaving downtown will cost the city $30 million in economic benefits per year. That may sound like a lot but it’s not.

Consider that Cleveland considered the $32 million per year in lost economic benefits by closing Burke Lakefront Airport as an acceptable loss. Why? Because the city estimated there would be an opportunity to gain $92 million annually in new economic activity by redeveloping the airport.

And that’s the calculus any city should be applying to the net fiscal impact of their stadium. If you don’t have the stadium, what else could you do with that land? Could you do something better? Then do it!

Sometimes, what is an acceptable loss can be confusing. Consider that Cleveland has also been willing to let go of the Cuyahoga County Jail, now located downtown, for suburban Garfield Heights. That’s more than 1,000 everday jobs at the Sheriff’s Department compared to 360 event-related jobs associated with a Cleveland Browns stadium.

Why are 1,000 jobs expendable but 360 jobs aren’t? Is it prestige? Certainly a National Football League franchise is more prestigious than a jail — even if the cold hard numbers show that having more than 1,000 workers taking care of nearly 1,700 prisoners on a daily basis may be more valuable to your taxbase than a professional football team that plays at home 10 times a year.

And yes, that doesn’t speak well for the economic contributions of a football team when a jail outperforms it. Perhaps it’s not too late to keep the jail in or near downtown. I know of a place that may be available for building a modern jail, but it would have to be more vertical than than the horizontal campus planned for Garfield Heights.

Back to the football stadium — taking away its 700,000+ annual attendance from downtown (610,000 from football games, another 100,000 or so from two concerts/events per year) sounds large. But, again, it’s really not.

The Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and Museum gets 600,000 visitors per year, and that’s before it’s $135 million expansion, now well underway. It doesn’t have to accommodate a mass surge of parking either. Neither does the Great Lakes Science Center which adds another 300,000 visits per year.

Planned for the lakefront is a multimodal transportation center that serves as a stop for the Greater Cleveland Regional Transit Authority (GCRTA) buses and trains, Amtrak trains, Greyhound and Barons buses, plus transit from collar-county transit systems like Laketran, Akron Metro, Portage Area and Stark Area. All Aboard Ohio says it could bring another 500,000 annual boardings.

The cost of renovating the existing Huntington Bank Field is just over $1 billion. Here’s a better way to invest that $1 billion — public transportation. According to the American Public Transportation Association, a $1 billion investment in public transit begets 50,000 jobs and $5 billion in economic impacts.

For $1 billion, we could build the lakefront multimodal transportation center, finish the Waterfront Line as a more useful Downtown Loop, reroute the Blue Line from Shaker Square to the new Loop via the booming University Circle, build the MetroHealth Line bus rapid transit on Pearl/West 25th and more.

Then you’ve got the European cruise ships that are docking in Cleveland. In 2023, there were 48 ships that brought 10,000 visitors to Cleveland. Next year, 56 cruise ships are due to visit. And the lakefront plan has a cruise ship terminal which could also be used by cross-lake ferry boats. Remember those?

In the 2010s, a slow, 4-hour ferry boat to Canada was projected to carry 250,000 people per year. A high-speed catamaran like the 2.5-hour Milwaukee-Muskegon Lake Express might do even better, especially if VIA trains to/from Toronto met the Cleveland boats at Port Stanley. A boat/train trip would be competitive with the best Cleveland-Toronto drive time.

What could replace the existing 31-acre football stadium on the lakefront? How about 1,000 housing units and several hundred hotel rooms supporting a neighborhood of ground-floor restaurants, retail, co-working spaces and interactive venues be they sports, creative, or other year-round activities. Parking for each building could be sandwiched between the ground-floor uses and the housing/hotel above.

Building 1,000 housing units on the existing stadium’s site could support twice as many residents while the hotel rooms could attract up to 1,000 visitors a night. That’s over 1 million people coming and going throughout the year — exceeding the most optimistic attendance scenarios for even a domed stadium right next to the heart of Cleveland’s downtown.

Not only does the seldom-used stadium itself occupy a lot of lakefront land, it demands a hinterland of 12,650 parking spaces at about 300 square feet for each or 3.8 million square feet total. That massive amount of parking infrastructure exists to support crush crowds 10-12 times per year — another massive opportunity cost for Downtown Cleveland.

If we built for thousands of routine, smaller, everyday activities rather than a dozen massive events, we’d have a much more vibrant downtown and lakefront nearly every day of the year. If there is to be a football stadium, don’t put it in the heart of downtown. Put its stadium-area development next to downtown, orient the stadium beyond that, and place most of the parking facilities beyond the stadium.

The design concept floated by Destination Cleveland — locating the stadium and its development on the 450-acre Burke Lakefront Airport — does most of that. It’s actually a good plan and warrants Congress expediting matters by telling the Federal Aviation Administration to close down Burke to meet the Haslams’ timeline.

Opportunity costs are why a stadium shouldn’t be right in the heart of downtown. Unfortunately, Cleveland is driven very much by its past. The past has nothing to do with where a stadium for the future should be.

And I say this as a Browns fan and as a history nut — the past causes us to be prejudicial about things that we should measure solely via a balance sheet including the cost of pursuing other options. Doing the next thing as we’ve done it before “because that’s how we’ve always done it” is the most direct route to obsolescence.

END