State support was last ‘big’ hurdle for Browns move

Barring a surprise, the last of the big hurdles appears ready to be surpassed for the Cleveland Browns football team’s move from downtown to Brook Park. Yes, there’s a million other things that can happen or not happen in the next year before financing might close and construction contractors are given the green light. But most of those hinge on events occurring now at committee hearings in our state’s capital.

The timing is driven by the biennial budget crystalizing in those committee meetings between now and the end of April. After April, the details of a decision are refined toward final passage in June. And, based on multiple media reports, our state lawmakers want the Browns playing their home games in Brook Park.

This is a “seal the deal” action because it is answering a critical question: whose state funding request will be included in the state’s next two-year budget starting July 1? Will it be Gov. Mike DeWine’s proposed stadium and sports education funding initiative, supported by a doubling of taxes on sports betting?

Up to $180 million per year could be generated from DeWine’s proposal, based on projections from existing sports betting revenues. But doubling the taxes will cause many gamblers to take their money elsewhere, including to offshore betting. Skeptics estimate the annual revenues will instead be $130 million or less from the doubled tax.

Funds for sports facilities and educational programs, from toddlers to the pros, would be competitively awarded as one-shot grants from that pot of funds whose revenues will vary from year to year. So it cannot safely be used as a revenue stream dedicated to retiring construction bonds over, say a 30-year period.

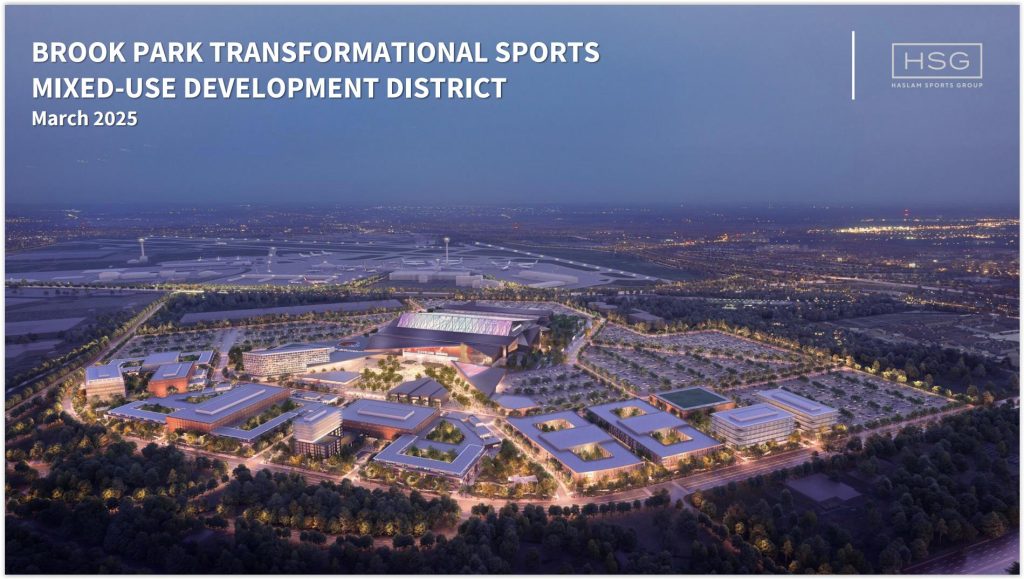

The Haslam Sports Group (HSG), owner of the Browns, have a purchase agreement to acquire 176 acres of land at 18300 Snow Rd., site of two former Ford auto plants. There, they want to build a $2.4 billion enclosed stadium plus $1.2 billion worth of adjacent hotels, housing, restaurants and stores.

The Haslams don’t want to compete for state funds with professional, collegiate, high school or primary school sports facilities and programs. It wouldn’t be a good look if the first four or five years of this new program went entirely to pay for a billionaire’s new toy while a moldy roof is leaking at an inner-city soccer training complex, or a rural school’s baseball field is a muddy mess for much of the spring.

The other option was for state lawmakers to embrace HSG’s proposed value-capture, tax-increment financing (TIF) mechanism of new state tax revenues generated by the new stadium, not existing sources, and any surrounding developments within a to-be-specified stadium district. And that’s where state lawmakers appear to be leaning toward while at the same time leaning away from DeWine’s proposal.

If DeWine’s proposal was probably the last hope of keeping the Browns in Downtown Cleveland in the existing stadium, albeit renovated for $1.2 billion. The design concepts exist for this stadium renovation but taxpayers have yet to see them. Our state lawmakers got to see them and said they were pretty impressive. But we’re just “We The People” so we didn’t get to see them.

DeWine offered his proposal to avoid having to pick a winner and loser in the Browns stadium debate. He apparently believed there would be a winner and loser based on where the Browns play starting with the 2029 NFL season. The Browns lease with the city of Cleveland for use of the lakefront stadium ends after the 2028 football season.

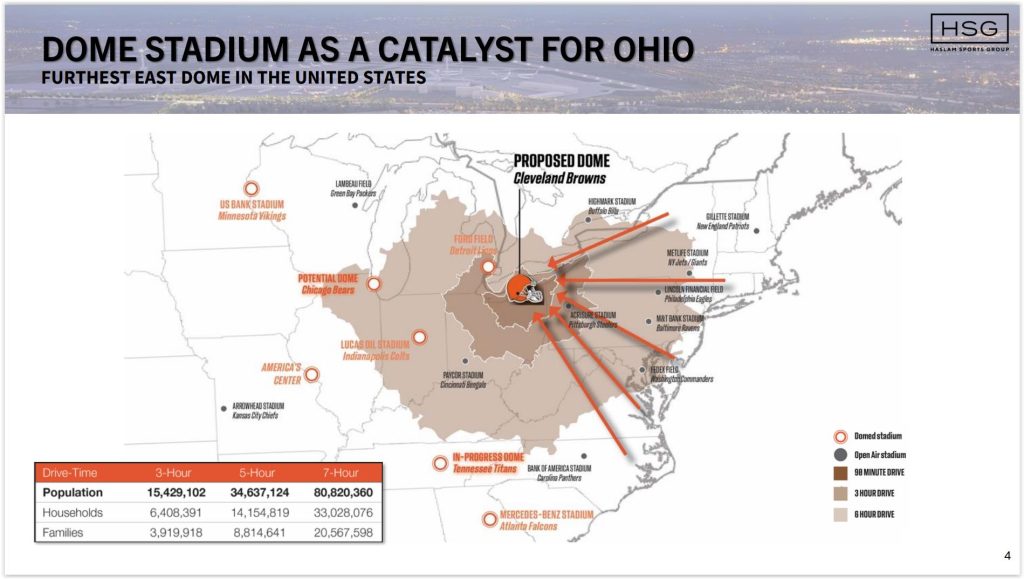

The Haslam Sports Group believes that by building an enclosed stadium will be a draw for those living to the east of Cleveland, especially along the East Coast. Their contention is that their proposed stadium would be the farthest east enclosed stadium of its size in the United States. It should be noted that whoever does the maps for the Haslams needs to brush up on their geography of where competing stadiums are located (HSG).

DeWine could also have supported both funding mechanisms but didn’t because that also would send Browns’ home games to suburban Brook Park. The question of where the Browns will play is still being weighed in the courts — another reason why DeWine didn’t want to pick a stadium site. Ohio lawmakers didn’t want to wait for the court’s opinion. Perhaps they already know how that will play it out.

In testimony earlier this week before the Ohio House of Representatives’ Arts, Athletics and Tourism Committee, HSG’s Chief Administrative Officer & General Counsel Ted Tywang, claimed that everyone wins if the Browns leave Downtown Cleveland for Brook Park.

“The Brook Park site is only 12 miles from Downtown Cleveland and just outside the Cleveland city limits, close enough for the dome stadium to have a substantial positive impact on downtown, particularly given the year-round activity and major events it will bring to the region,” Tywang said. “The new Huntington Bank Field enclosed stadium project will be complementary to downtown — not competitive.”

He also proposed that, with “optimal local collaboration,” the local fiscal impacts from the Brook Park stadium and development zone could not only pay for the local investment in the stadium, but also generate considerable excess public revenues that could be used for future capital repairs in the building and other important public purposes, including the downtown lakefront project. But will we get “optimal local collaboration” in a region where it has yet to happen?

HSG’s proposed state funding mechanism would be to designate in law a TIF district from which state tax revenues would be dedicated for several decades to service an issuance next year of up to $600 million in construction bonds. If state lawmakers are confident in this proposal, the chances of a Brook Park Stadium look pretty good.

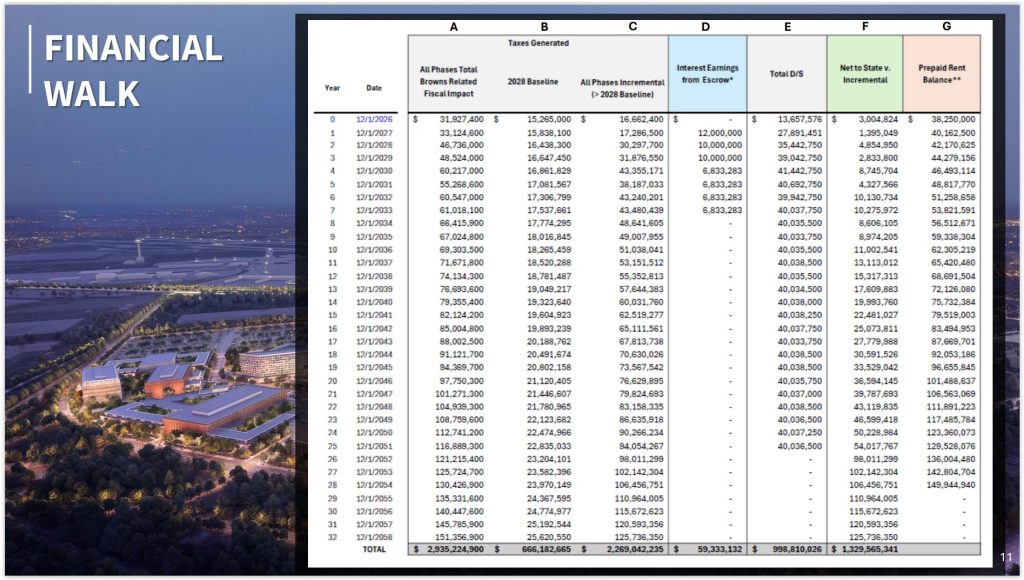

Projected revenue sources and amounts spread over 32 years to retire construction debt. Of particular interest is the column at the far right showing the Haslam Sports Group’s proposed reserve, or pre-paid rent balance, intended to reassure state lawmakers that this stadium won’t be a financial drain for Ohio taxpayers (HSG).

But there are concerns that the Haslams’ revenue estimates are too rosy. Critics doubt that they will be able to attract enough non-football events throughout the year to Greater Cleveland to attract a meaningful number of new visitors. Those visitors would be needed to generate new state tax revenues from the stadium and from proposed new hotels, shops and restaurants. Will the developments come? Will the visitors come? Will the tax revenues come?

Among those concerned is Cuyahoga County Executive Chris Ronayne who has questioned the Haslams’ projected numbers of Brook Park stadium visitors. He represents another group of potential stadium investors from which the Haslams want support — the taxpayers of Cuyahoga County. They now pay a 30-year countywide sin tax generating about $120 million total during that three decades to retire the bonds for the lakefront stadium built in 1999.

Whether that gets extended and redirected to a new Brook Park stadium first depends on if Ronayne and the Cuyahoga County Council put it on the ballot. So far, they continue to say they would do so only for a downtown stadium. But perhaps the Haslams can make them an offer they can’t refuse — such as a big donation to help lakefront redevelopment? Browns sources have told NEOtrans the Haslams are offering.

Another $480 million would be generated by local taxes generated by the stadium and its hoped-for development district. The Haslams have tried to reassure city officials and taxpayers in Brook Park that their city services won’t be risked by this investment. Some have asked how can a small city like Brook Park can afford a stadium this big.

The city contribution is based on the tax and parking revenues that can be generated by the facilities in each community, be it a renovated stadium in Cleveland or a new, doubly expensive stadium in Brook Park. But more revenues are possible with the proposed Brook Park location than with the existing downtown location.

Looking toward the proposed Brook Park stadium surrounded by thousands of parking spaces from which the Haslam Sports Group would control all of the revenues. Nearly everyone will have to arrive by car since the most direct walking path from the Brookpark Red Line station is nearly 1 mile long. A new path built along the tracks into the stadium could shorten the walk by about 500 feet. There are no plans to link the stadium with Hopkins International Airport and its Red Line station (HKS).

So the municipality is merely a legal conduit through which the local values and tax revenues from them can be captured. Scale of the project matters. Scale of the municipality does not.

Tywang displayed a chart to state lawmakers (shared earlier in this article), showing them that the Brook Park stadium’s financial numbers do work — if you are confident that the Haslams can attract the number of events and visitors they claim they can. The revenue data is spread over 32 years to retire construction debt.

To reassure state lawmakers, HSG added a column on the far right side of the financial chart. That column is a proposed reserve, or pre-paid rent balance, showing that HSG intends to provide a deposit of $38.25 million to back-stop their pitch that stadium won’t be a financial drain for Ohio taxpayers. That reassurance is what finally won over the lawmakers.

They were willing to overlook HSG’s management of the Browns team. How the Browns have done on the field should have an effect on whether we trust them with taxpayers’ money. The team’s trade for and gross overpayment of Quarterback Deshaun Watson has been an unmitigated disaster that continues to endure. Some football analysts call it one of the worst trades in football history.

HSG and the Browns mortgaged their future by paying Watson the most guaranteed money for any quarterback in NFL history — until Buffalo’s highly rated Josh Allen got paid more this week. And HSG/Browns gave up three first-round draft choices for Watson who has played fewer than half of the available games since he joined the Browns in 2022.

But it seems state lawmakers are willing to overlook that and believe HSG will be good stewards of taxpayers’ money. I would like to know why. Was the downtown lakefront stadium alternative really that bad compared to Brook Park? Were current/former managers of other domed stadiums asked to testify whether the Haslams have a shot at attracting that many non-football events?

We The People were never given the opportunity to make an informed choice of how to instruct our public servants to act. So, barring a miraculous legal outcome or some other surprise, it looks like Brook Park is going to be the place where the Browns play at home.

Given that the average cost for a family of four to attend an NFL home game was over $800 in 2024, how many of us taxpayers will be able to attend? Maybe it will look good on TV, unless all of the games end up on a subscription service.

END