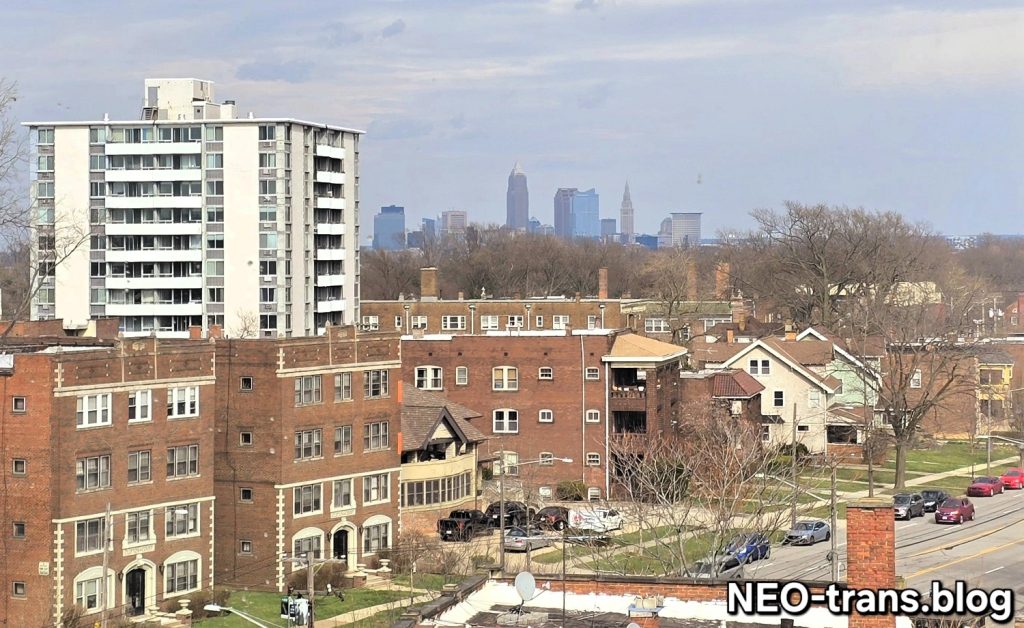

Greater Cleveland continues to struggle with an aging housing stock, much of which was built before the region’s population stopped growing in the 1960s. Now, most of its new housing stock is in the exurban counties where population growth is occurring at the expense of older, already established communities (NEOtrans). CLICK IMAGES TO ENLARGE THEM.

Cleveland shifts as childless households replace families

New estimates from the U.S. Census Bureau show that, while population in Greater Cleveland edged up a bit for the second straight year, the metro area is still down overall for the decade so far. And the city of Cleveland saw its population shift at the same it enjoys strong increases in income tax revenues from young professionals and retired empty nesters replacing lower-income families.

These are all factors driving the real estate market in the metropolitan area. They’re why developers can’t build high-end apartments fast enough in urban hot-spots like Downtown Cleveland, University Circle, Ohio City and Tremont.

Or why affordable housing is in such short supply, despite efforts to fund more of it. Or why single-family homes continue to pop up like dandelions in former corn fields in the collar counties surrounding Cuyahoga.

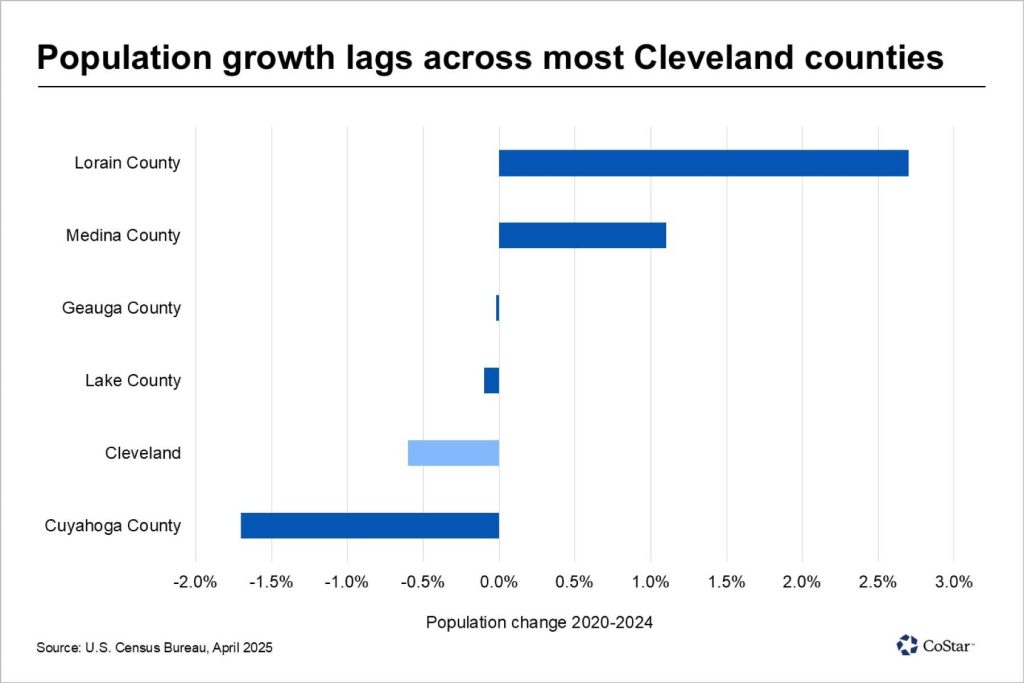

Census data shows that population in Greater Cleveland (Cuyahoga, Geauga, Lake, Lorain and Medina counites) grew by 5,600 residents last year to 1.867 million people — an increase of 0.3 percent. It was also the second consecutive year that the metropolitan region’s population expanded.

Yet it failed to overcome population losses in the previous three years, from 2020 to 2022. Greater Cleveland’s population was 0.6 percent higher in 2020 than it was last year, the Census said.

That growth was attributable to two of Greater Cleveland’s counties — Lorain and Medina. Lorain County’s population increased every year since 2020, racking up cumulative gains of 2.7 percent. Last year’s gain was 0.9 percent, putting the population number at 322,030.

Medina County saw its cumulative gains since 2020 amount to 1.2 percent, to 184,625 people. Its year-over-year growth last year was 1.1 percent, the latest in a series of steady increases.

“Several factors are drawing new residents to these two counties, such as lower tax rates, highly-rated public schools, and business expansions that are bringing jobs to the region,” said Veronica Miniello of CoStar Analytics. “These counties are also viewed as being more affordable compared to other Cleveland-area counties.”

Those population increases in Lorain and Medina counties and a total lack of new construction of apartments in those areas have conspired to tighten multifamily vacancy and drive up rents, CoStar data shows.

“Net absorption, the net change in (apartment) occupancy, over the 12-month period ending in the first quarter of 2025, was more than double the pre-pandemic net absorption average in Lorain County,” she added.

Lake and Geauga counties also saw their populations edge lower by less than 0.2 percent so far this decade. The biggest population loser in the region continues to be Cuyahoga County, which saw its population fall 1.7 percent so far this decade.

But that changed last year when its population increased by nearly 2,000 people thanks to international migration. Deaths in Cuyahoga County outpaced births by 215, and 6,741 people moved to other states or other Ohio counties. Those losses were offset by a net gain of 8,876 immigrants.

The city of Cleveland is no longer the biggest contributor to Cuyahoga County’s decades-long population slide, as its population since 2020 dipped by only 0.6 percent, the Census said.

It used to be that only penthouses in Downtown Cleveland or lakefront homes in Edgewater would sell for $1 million or more in the city of Cleveland. Now, there are houses selling for more than $1 million in Little Italy, Ohio City, Tremont and Detroit-Shoreway due to an influx of wealthier residents (Zillow).

Cleveland isn’t experiencing an exodus of population like it used to, or like other parts of Cuyahoga County are now. Instead, it is seeing an enduring trend of a population “trade.”

Over the past decade, higher-income singles and couples, as well as retirees, all mostly childless, are replacing lower-income families who are mostly relocating to other parts of the county and the region, according to multiple sources in the real estate industry who call this The Fifth Migration.

This is borne out in Cleveland’s stunning income tax revenue trends. In 2020, Cleveland collected $410 million in income tax revenues which provided and continues to provide for about two-thirds of the city’s budget.

Earlier this year, the city’s fiscal forecasters conservatively estimated that Cleveland will take in $508 million in income tax revenues in 2025 and grow to $575 million by 2030 — a huge 40 percent increase for the decade.

That is the opposite of what many market observers feared would happen as a result of the pandemic and remote working. Instead, all of the income taxes diminishing from tenants reducing their office spaces in Downtown Cleveland are being more than offset by wealthier people moving into Cleveland.

The city of Cleveland experienced a brief, pandemic-induced drop from 2019’s income tax revenues of $442 million. But even 2020’s revenues were far higher than those of just a few years earlier when the city raked in $389 million, city financial records show.

While Greater Cleveland is still the cheapest real estate market among the nation’s 40 largest metro areas, it may not be for long. According to CoStar’s Homes.com, real estate prices in Greater Cleveland are rising year-over-year each month in 2025, with March’s being the strongest among any of the United States’ largest metros.

A tight housing inventory is also a major factor in those price increases affecting for-sale, single-family homes as well as apartments. The vacancy rate for the Greater Cleveland multifamily market overall will also likely tighten over the medium term, as the pace of completions is expected to pull back significantly in 2026, according to CoStar’s forecast for the Greater Cleveland market.

END