Reducing freight train traffic off Downtown Cleveland’s lakefront is a realistic possibility, one that was bolstered by a similar project in Milwaukee that was just funded by the federal government. One of the benefits would be to reduce the amount of time the Norfolk Southern drawbridge at the mouth of the Cuyahoga River is lowered for so many long freight trains (KJP). CLICK IMAGES TO ENLARGE THEM.

Milwaukee bypass has similarities to Cleveland

A COMMENTARY

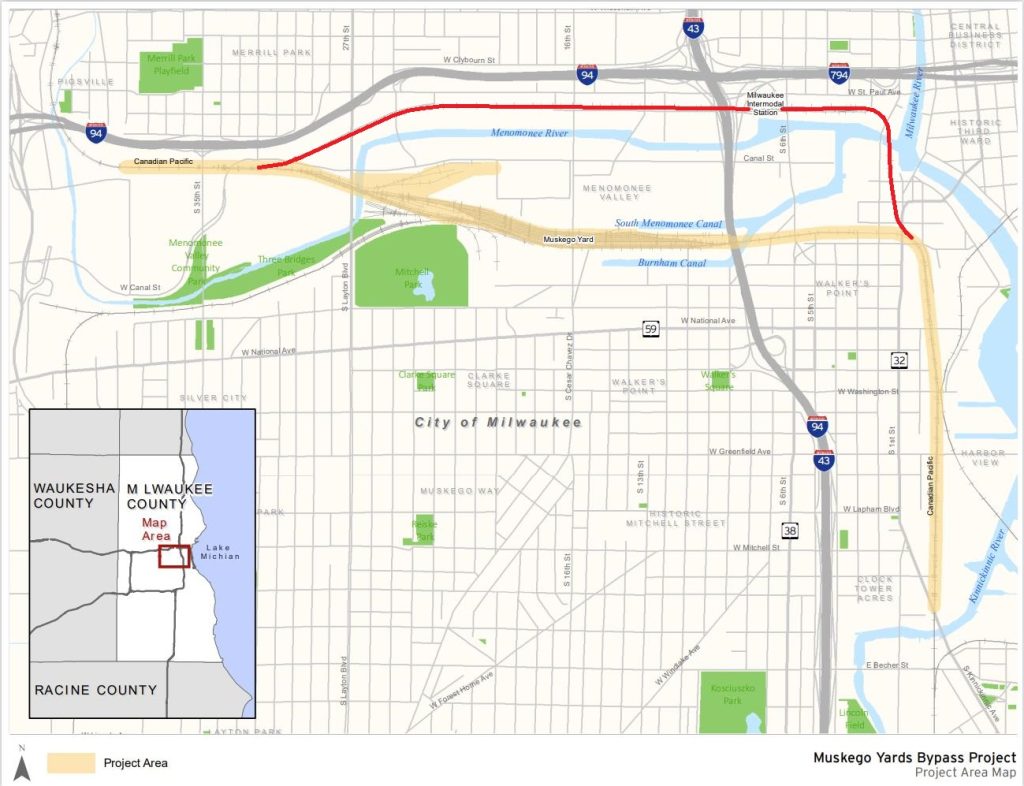

One month ago, the Wisconsin Department of Transportation (WisDOT) won a $72.8 million federal grant to reroute freight train traffic south of the Menomonee River and away from Downtown Milwaukee. The project has many similarities to a local concept for rerouting most freight traffic south of Downtown Cleveland, away from the lakefront.

In Milwaukee, WisDOT put up $13 million in matching funds toward the $92.8 million Muskego Yard Freight Rail Bypass. Passenger railroad Amtrak provided another $7 million. The latter is a stakeholder because the bypass would reroute all two dozen daily Canadian Pacific Kansas City Ltd. (CPKC) freight trains out of the Milwaukee Intermodal Station that is served by 16 daily passenger trains.

Amtrak and WisDOT plan to expand the number of passenger trains south to Chicago and west to Minneapolis-St. Paul. They need more track space at Milwaukee Intermodal Station without being able to build more tracks through the limited confines of that five-track station.

Instead, they will gain capacity by building a side-by-side pair of mainline-quality tracks for freight trains south of the station, through the Muskego Yard on the other side of the Menomonee River. The new route is 2.3 miles long, including an expanded bridge over the Burnham Canal. But the total project area is 4 miles long, as some additional track and signal system improvements extend beyond the new bypass section.

The orange shaded rail corridor represents where the $92.8 million will be spent to provide the Muskego Yards Bypass around the rail corridor, shown in red, through the Milwaukee Intermodal Station. It is anticipated that the bypass will open more capacity at the station for more passenger trains to Chicago and Minneapolis-St. Paul (WisDOT).

The Ohio Rail Development Commission (ORDC) and its consultant team of HDR and HNTB may come to a similar conclusion about Cleveland’s lakefront as it delves in the coming months into the Phase I passenger rail Service Development Planning for both the Cleveland – Columbus – Dayton – Cincinnati (3C&D) as well as the Cleveland – Toledo – Detroit Corridors.

Both corridors could add a dozen additional daily passenger trains to the already congested Norfolk Southern Chicago Line between Berea, 12 miles southwest of downtown near Cleveland Hopkins International Airport, and Downtown Cleveland’s lakefront. There, the city of Cleveland in its lakefront project plan seeks to add a multi-modal transportation center for current and future Amtrak trains, plus Greater Cleveland Regional Transit Authority buses and trains.

Providing those things may ultimately demand a remedy similar to Milwaukee’s — a Lakefront Bypass for freight trains. The minimum amount of new infrastructure needed to open up the Lakefront Bypass appears remarkably similar, too.

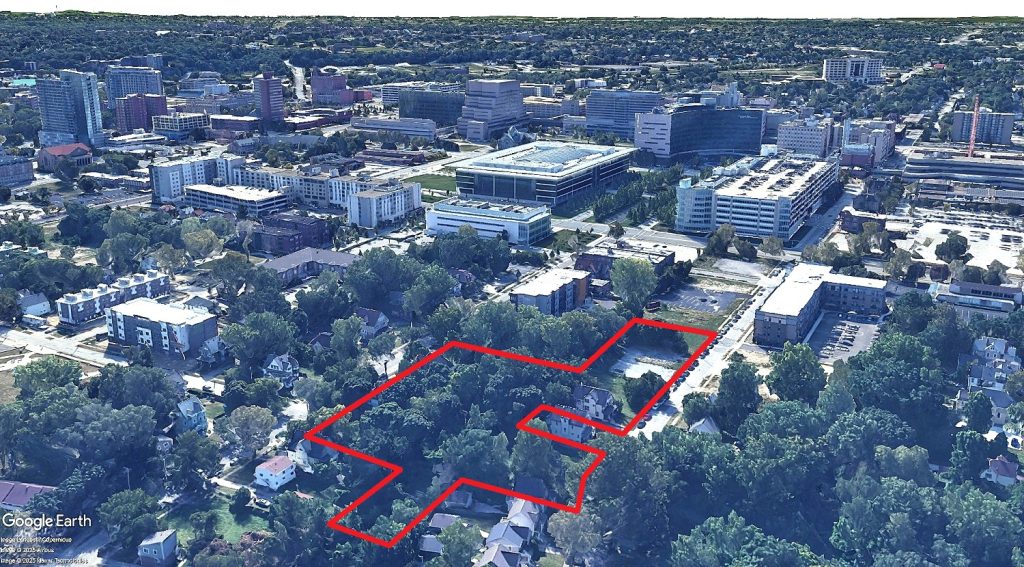

About 2.8 miles of new, side-by-side pair of mainline-quality tracks for freight trains could be built in Cleveland. Its routing would be along the disconnected, rusty remnants of the former Erie-Lackawanna railroad right of way, owned by Norfolk Southern. Southeast of downtown, it would start at East 37th Street, below Interstate 77 and end near a railroad junction called Erie Crossing, close to Union Avenue and East 82nd Street — at minimum.

A Canadian Pacific Kansas City Ltd. freight train rolls slowly through the Milwaukee Intermodal Station, occupying track space for more passenger trains that are planned in the coming years. It also creates a lot of noise, emissions and vibration in the station’s train shed, making for a less pleasant setting for passengers (Benesch).

The minimum Lakefront Bypass infrastructure may ultimately require more changes to the railroad corridors it would link up, such as realigned approach tracks to allow safer, more gentle curves. This could mean a total project area comparable to that of Milwaukee’s railroad bypass. Milwaukee’s experience also gives a sense of what the minimum Lakefront Bypass could cost to build. And we could learn from their experience as well.

Another similarity is that Cleveland’s minimum bypass could allow Norfolk Southern to reroute a couple dozen of its freight trains off the lakefront, just like what CPKC will do after the Muskego Yard Freight Rail Bypass opens in 2029. Why do I keep calling this potential infrastructure on Cleveland’s southeast side the “minimum” Lakefront Bypass?

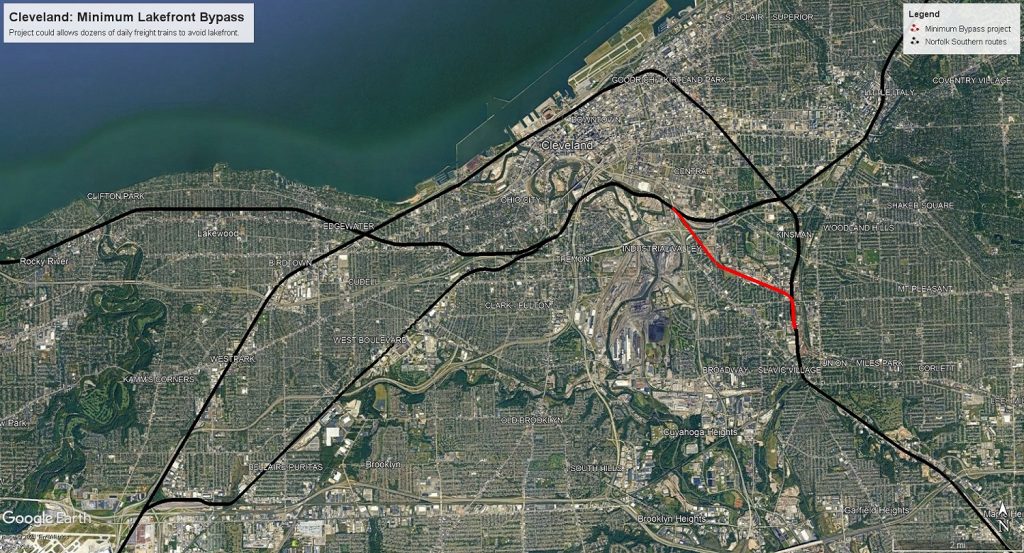

Because the minimum bypass, which is comparable to Milwaukee’s, merely opens up a modest, all-Norfolk Southern-owned path where none exists to accommodate a portion of Cleveland’s rail traffic. And in Cleveland there’s a lot more freight train traffic to reroute.

Norfolk Southern’s main route through Cleveland — called the Chicago Line west of downtown and the Cleveland Line southeast of downtown — is the busiest freight railroad between Chicago and the East Coast. Its mainline through Cleveland hosts up to 70 freight trains per day carrying 100 million gross tons of freight shipments per year. That’s nearly three times as much freight rail traffic as what CPKC sends through Milwaukee.

The Norfolk Southern-owned rail corridor shown in red hasn’t been intact for 40 years but could be rebuilt with two mainline quality tracks so that one-third of the rail traffic now operating via the Downtown Cleveland lakefront can bypass it. To reroute all through freight train traffic may require extensive additional infrastructure improvements on Norfolk Southern-owned tracks shown in black to near Cleveland Hopkins International Airport at the far lower-left portion of the image (Google/KJP).

So while detouring a couple dozen freight trains per day does a full and complete job in Milwaukee, it would only make a dent in the rail traffic past Downtown Cleveland’s lakefront. To remove all through freight train traffic would involve adding more tracks and other expensive infrastructure improvements farther west to and through Norfolk Southern’s Rockport Yard near Hopkins Airport.

In full disclosure, I should note that I was hired two decades ago to research and write a report by the Cleveland Waterfront Coalition (since succeeded by the Green Ribbon Coalition) and EcoCity Cleveland (now the Green City Blue Lake Institute). The purpose of that research was to figure out the best way to reroute as much train traffic off the lakefront as possible and to identify its benefits and costs.

Perhaps the biggest benefit of the bypass is to improve Cleveland’s quality of life. We would have a more enjoyable lakefront where heavy freight trains up to three miles long aren’t creating a nuisance for their residential and recreational surroundings. There are more residential and recreational areas along the lakefront routing than there are along the bypass.

Rerouting all of those long freight trains also would mean not blocking as much recreational and commercial water traffic on the Cuyahoga River. Nor would it bring large quantities of hazardous materials past a public waterfront and a water supply for more than 1.4 million residential, commercial and industrial consumers.

City of Cleveland officials want a multimodal transportation center attached to its planned North Coast Connector land bridge over the lakefront railroad tracks. To fully capitalize on its proposed lakefront improvements could mean removing as much freight train traffic as possible and expanding passenger rail access to the transportation center (FO).

And it would open up a lakefront routing for current and future passenger rail services, be they Amtrak intercity trains or regional commuter trains, both of which are lighter, much shorter and don’t carry hazardous materials. The planning for those services could spin out a Lakefront Bypass project based on its own separate utility.

Adjusted for inflation, development of that full, 13-mile-long Lakefront Bypass along existing Norfolk Southern rail corridors might cost $300 million if built in 2030. It’s a heavy lift which might be easier to do if pursued in smaller pieces, starting with the minimum, even if the whole thing was designed at the outset.

The minimum Lakefront Bypass could cost one-third of doing the whole thing. And it would offer immediate benefits to the community by rerouting the general freight trains that carry hazardous materials, leaving only the Amtrak passenger trains, Norfolk Southern’s fast, intermodal freight trains that carry truck trailers and shipping containers which typically don’t haul anything toxic, plus a few daily freight trains to local shippers including the Port of Cleveland.

Cities and states sometimes shy away from big railroad projects because they don’t have jurisdiction over interstate commerce. Only the federal government does. But cities and states can encourage railroads to change their operations in a way that benefit all parties by making targeted capital improvements. That is happening in Milwaukee and it could happen here, too.

END