Above the Flats’ West Bank, Cleveland could have its own scaled-down version of New York City’s High Line park if early talks bear fruit.

The site is the Superior Viaduct that was completed in 1878 but closed to traffic in 1920. It’s primary use over the past 20 years is as a parking lot for K&D Group’s Stonebridge development that includes apartments, condominiums, restaurants, galleries and offices. The viaduct’s former roadway deck, still hosting streetcar tracks from long ago, is largely barren.

But several major developments are in the works along the historic span and are prompting talks about higher uses for the sandstone-block viaduct than just a parking lot. The uses being discussed could feature more attractive settings, interpretive historical exhibits, recreational programming in addition to the existing, unique views of the downtown skyline, bridges and Cuyahoga River traffic.

Those talks were referenced at a meeting today of the Waterfront District Block Club at which conceptual plans for a 25-story apartment tower won support prior to review by the City Planning Commission. Nearly 40 people were in attendance at today’s block club meeting.

“We’ve just had some very early conversations about how to make the viaduct spectacular,” said Ward 3 Councilman Kerry McCormack.

“Provided that we have a project, yes we’d be excited to be a part of it (a viaduct park),” said Wayne Jatsek, representative of the development group pursuing the high-rise tower at 2208-2210 Superior Viaduct. Theirs was the first project reviewed by the relatively new block club and the first of several developments proposed in response to the city’s new 250-foot height district for the Flats West Bank.

“I think it’s a benefit to the entire city,” said Scott Aylesworth, president of the block club. “The High Line in New York City is now the number-one tourist draw for all of New York City. Cleveland needs more parks and open space for people to enjoy. Realizing the dream of an activated outdoor space can only enhance the city and the Waterfront District Block Club is working to improve Cleveland for all Clevelanders.”

The remaining portion of the Superior Viaduct is a little more than 1,000 feet long. The non-bridge roadway of Superior Viaduct continues west nearly 300 feet before it encounters its first intersection — West 24th Street.

|

| Parking uses dominate along the western half of the Superior Viaduct which is leased by K&D Group from the city (KJP). |

That one-quarter of a mile is quite a bit shorter than the 1.5-mile High Line that winds its way through the Chelsea section of Manhattan. The High Line was built in 1934 by the New York Central Railroad to service cargo docks and food warehouses along the Hudson River side of Manhattan. It was rebuilt starting in 2009 as a public park for $153 million and costs $3 million per year to maintain. The High Line has attracted $2 billion worth of development along it.

But the High Line is only 30-55 feet wide compared to Superior Viaduct’s 60-foot width. The Superior Viaduct was replaced by the Detroit-Superior High Level Bridge in 1918. The old viaduct was closed in 1920 and its iron-built eastern approach and swing bridge over the Cuyahoga River were demolished in 1923. Three stone arches closest to the river were demolished in 1939 so the river channel could be widened.

“Using this space as a place for families to come and hang out will be a far better utilization than a parking lot,” Aylesworth said. “We have seen how much of a success the East Bank development is and all of the residents who come out and enjoy the connection to the waterfront. With the new Wendy Park connector bridge nearing completion next year, the West Bank will hopefully become a vibrant community and another opportunity for residents to engage with the river and lake.”

But K&D Group’s CEO Doug E. Price III said that Superior Viaduct is fine the way it is. The westernmost 400 feet of the viaduct has about 140 parking spaces for Stonebridge residential, office and restaurant tenants while the eastern 600 feet is closed to vehicular traffic and open only to “pedestrians traffic and somewhat of a park,” he said.

“We have a long-term lease with the city,” Price said in an interview. “We renovated it (the viaduct) at our own expense probably about 20 years ago. We have a park at the end with the parking area to the west and that’s the way it was set up.”

The city’s 40-year lease began in 2000 with K&D affiliate Stonebridge Phase One Ltd. which pays the city $1 per year. In 2040, the city and K&D can renew the lease every two years thereafter. K&D’s affiliate must make the viaduct open to public/pedestrian access on a daily basis between 7 a.m. and 10 p.m. It was also supposed to complete construction of improvements within two years and clean the stonework within three years.

The lease refers to the zoning code on how the viaduct was to be improved and used by K&D.

“Stonebridge Phase One Ltd. has proposed to lease the Old Superior Avenue Viaduct for the purpose of reconstructing, rehabilitating, preserving and maintaining the structure for use in connection with a planned residential and retail development to be constructed consistent with a Planned Unit Development Overlay District,” the lease reads.

| This was K&D’s vision for Superior Viaduct nearly 20 years ago — showing no parking on the historic bridge (Corna). |

The arrangement of land uses in planned unit development zoning is established by a site plan approved by the city. Price contends the current use conforms to that plan. NEOtrans has Stonebridge’s site plan from 20 years ago but that site plan is silent on how the viaduct should be used (rendering is above, site plan is below). Aylesworth disputes Price, referring to a rendering K&D and its architect Bob Corna provided to the city 20 years ago.

The lease also says that the agreement should not be construed as a partnership between the city and K&D. It allows the city to walk away from the lease if a public purpose for the viaduct, such as a park, is identified.

“This lease may be terminated prior to its expiration by the director of public service should the city reasonably need the leased premises for public purposes,” per the lease.

The block club encouraged removing parking from the viaduct and putting it into a proposed parking garage on Nautica’s land. But that proposal has gotten mixed reviews depending on who you talk to.

|

| K&D’s Stonebridge site plan in the early 2000s was silent on planned uses for the viaduct. It showed a never-built phase 8 that was to have structured parking (Corna). |

“We would be happy to talk to Kerry (McCormack) and the other (Flats West Bank) developers about it (the garage),” Jatsek said.

“I have no idea what the block club is,” Price said. “And that tower is the craziest thing I’ve heard of, especially now (with the pandemic-induced economic slowdown).”

Aylesworth, a Stonebridge resident, acknowledged that he and Price have had some run-ins in the past regarding the development of Stonebridge. But he contends that his block club is serious about the park and has a fiscal agent with tax-deductible status so they can start receiving donations and other funding to work with a designer to develop concepts for the park.

He estimates that the park improvements could cost about $1 million although the High Line’s repair, remediation and development costs were much more — upwards of $10 million per tenth of a mile on average.

|

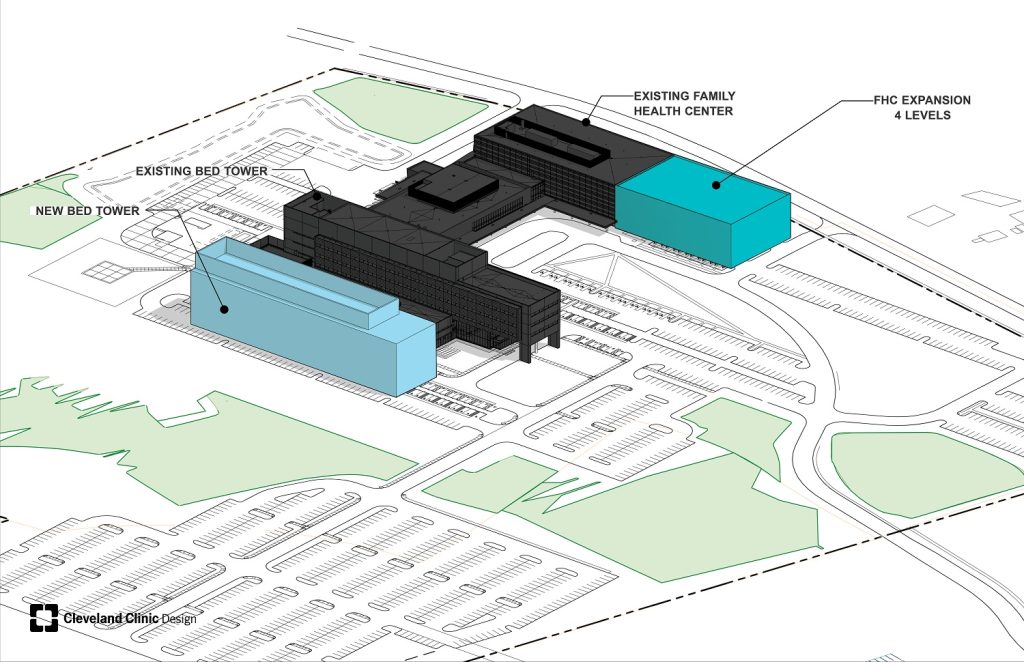

| A refined proposal for 2208-2210 Superior Viaduct won support from the Waterfront District Block Club on June 15 (Dimit). |

“The High Line bridges were in terrible condition and had serious environmental issues,” he said.

The High Line is surrounded by new development and so might Superior Viaduct be someday, in addition to Stonebridge’s buildings, including two 11-story mid-rises. Jatsek said that his group which oversees an Opportunity Zone fund could start construction a year from now.

Jatsek added that his group’s high-rise tower was redesigned with input from the block club, including increasing the number of structured parking spaces from 128 to 161. The number of apartments was cut from 186 to 173.

Paul Glowacki of Lakewood-based Dimit Architects said the exterior of the tower was slimmed down through the upper eight floors and the exterior design used more exposed steel to give the building a more industrial look. Both were in response to public comments made at the last block club meeting, including one that said the building looked like something one might find in Miami.

Although the City Charter or ordinances don’t require a block club’s endorsement before a development project can be approved by City Planning Commission, McCormack encourages developers to get input from block clubs before submitting their projects for approval by the commission’s Design-Review Committee.

END