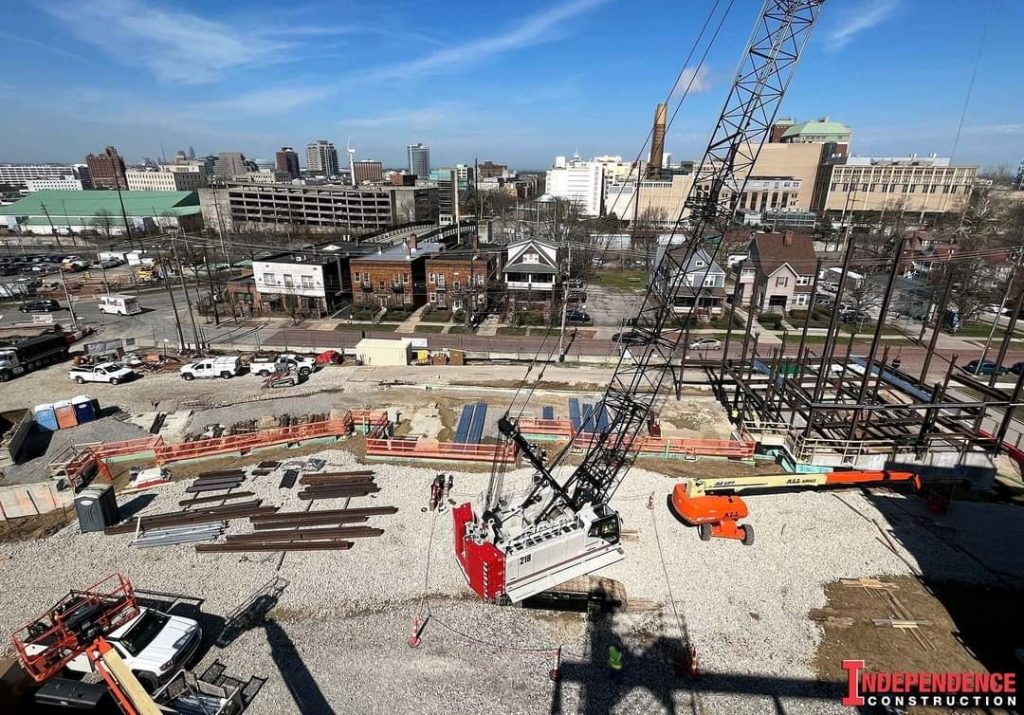

Construction has been one of Greater Cleveland’s most robust job sectors for growth as has education/health services. Both employment sectors are represented here in this photo of Case Western Reserve University’s expansion of its South Residential Village in the University Circle-Little Italy neighborhood (Independence). CLICK IMAGES TO ENLARGE THEM.

Labor, housing, jobs kept at a distance

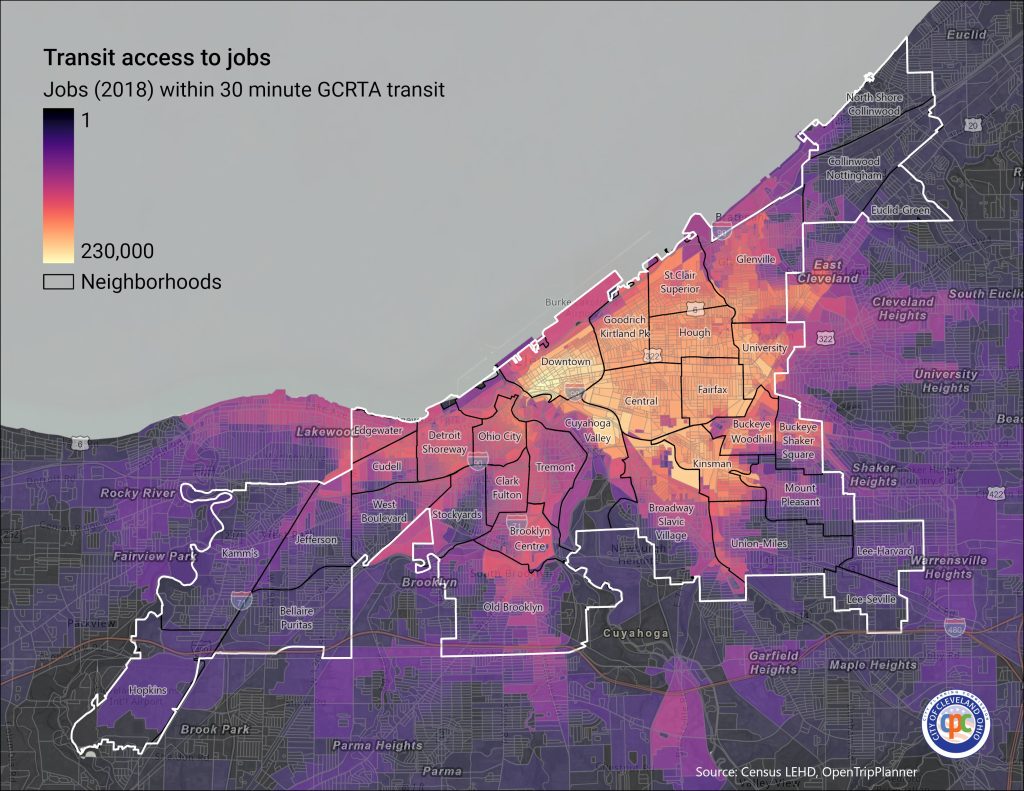

Amid the good news in Ohio and especially in Greater Cleveland that unemployment has fallen to pre-pandemic lows is the harsh reality that inner-city joblessness remains high. This is despite thousands of jobs made available by economic growth and retiring Baby Boomers. Meanwhile, three-fourths of all available jobs are beyond the reach of public transportation or, where public transportation is fast and frequent, there are many jobs but few quality housing options.

Those are some of the takeaways in response to jobs data released last week by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). The preliminary data showed Greater Cleveland’s unemployment rate in April fell to 3.4 percent. That tied December’s rate, which was the best unemployment rate since before the pandemic — fall 2019. But December’s rate was influenced by holidays-related hiring. It is more relevant to compare April to past Aprils. Last month was the best April unemployment rate since April 2001 when it dipped to 3.1 percent. The lowest unemployment rate since 1990 — the oldest and most readily available data — was 1.7 percent in August 1998, BLS records show.

The fastest-growing job sectors last month were Other Services at 7.2 percent, Construction-Mining-Logging at 6.1 percent and Education-Health Services at 4.9 percent. The latter is Greater Cleveland’s largest employment sector with 206,800 workers. The next largest are Trade-Transportation-Utilities with 177,500 employees and Professional-Business Services at 154,100 workers. The BLS said those sectors fell in April by 3.8 percent and 0.7 percent, respectively.

Manufacturing, once Greater Cleveland’s dominant sector, is now only it’s fifth-largest at 120,500 laborers, right behind government’s 130,300 employees. The Associated Press last week reported that Greater Cleveland has 10,000 unfilled manufacturing jobs, made available by growth in that sector as well as by retiring Baby Boomers. The AP also reported about philanthropic efforts to train workers in Cleveland where the unemployment is two to three times higher than the region’s average.

This map shows areas where jobs would be most transit-accessible, not necessarily where most of the jobs are. The most transit-accessible areas of Greater Cleveland are from downtown into the near-east side of Cleveland which is also where jobs are needed most to address chronic poverty. The city is creating a job-ready sites fund to clean up blighted, difficult-to-develop land to compete with exurban greenfield sites (CPC).

Training is half of the equation to filling those jobs. Physical access is the other, as noted by many community development officials. Fortunately, efforts to get the labor force to the jobs and the jobs closer to the labor force are getting more attention. Planning departments at the city of Cleveland and Cuyahoga County are devoting more time and effort to address the transportation and land use development causes of geographically based chronic poverty by incentivizing Transit-Oriented Development (TOD).

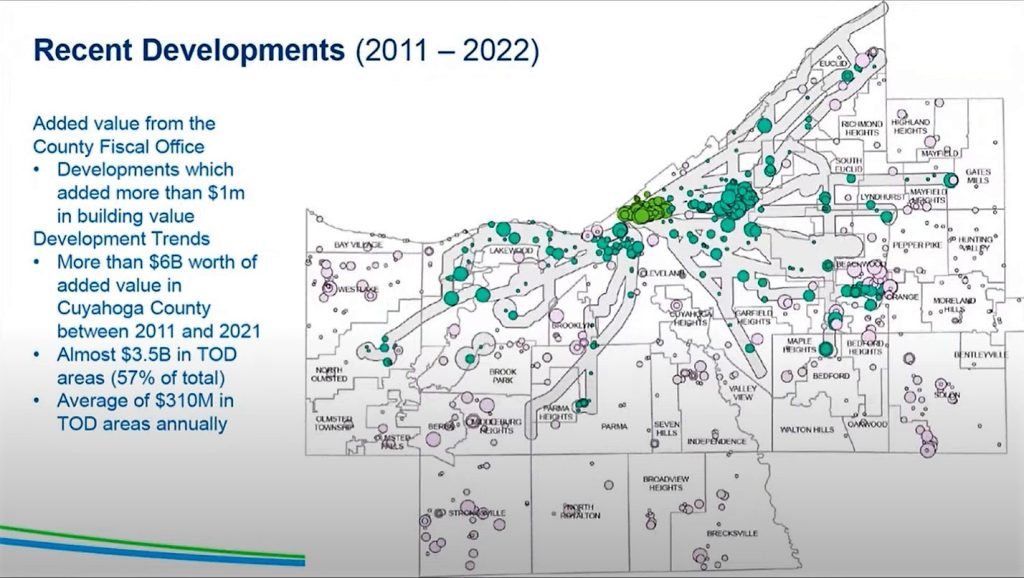

“There remains significant opportunities to add density and development along TOD corridors,” said Patrick Hewitt, planning manager strategy and development at the county’s planning commission at a public meeting last fall. “More area is being used for parking than buildings in the corridors where we’ve invested in frequent and rapid transit.”

Within a quarter-mile “walkshed” of bus routes offering daytime departures every 15 minutes or better and within a half-mile walkshed of rail stations, only 17 percent of land in those areas is used for buildings; 25 percent is used for parking, according to a report issued last year by the Cuyahoga County Planning Commission. Unless they’re hiring valets, parking lots don’t offer jobs. Another 45 percent of land is devoted to greenspace and 12 percent of land use near transit stops was identified as roads. Even in Cleveland, most transit-supportive land uses are illegal under the city’s zoning code. The county is working with Cleveland and its suburbs to adopt transit-supportive zoning.

Bringing middle-tier housing and jobs closer together in a setting that’s safe for walking and biking is another matter that can help get available jobs filled. Few areas have as many available jobs as the University Circle area, including neighboring Fairfax. It’s the epicenter of Greater Cleveland’s dominant eds-and-meds employment sector. Projects like the Stokes West apartment complex, which is designed with workforce housing, will put 261 residences in a setting that’s about to get more walkable thanks to planned improvements to calm traffic on wide, nearby streets.

The greenish dots represent recent, transit-accessible developments that added housing and jobs since 2011. The larger the dots, the bigger the investment. The wide gray lines and dots are areas within a short walk of a high-frequency bus route or train station. The pinkish dots are real estate development that are not transit-accessible (CPC).

Cleveland Planning Director Joyce Huang said the city’s new major transportation projects coordinator will be working on an effort to calm traffic on Martin Luther King Jr. Drive and on Stokes Boulevard in University Circle to make it safer for walking and biking. Streets on Cleveland’s East Side are more dangerous to pedestrians and cyclists because they are designed for speed. Redesigning them less for cars and more for people will help reduce fatalities and serious injuries, city officials said.

Regional development officials lauded Cleveland’s new $50 million site readiness fund to turn 1,000 acres of blighted, polluted sites into job-producing properties. The city intends to use federal American Rescue Plan Act funds to leverage another $50 million from other sources to create shovel-ready sites for new employers and be better able to compete for jobs with greenfield lands in the exurbs that far beyond the reach of transit services. Until then, the blighted properties are an obstacle to addressing chronic poverty.

“They aren’t ready for companies to move to or, in many cases, even for developers to develop,” wrote Bethia Burke, president of Fund for Our Economic Future on their organization’s blog. “Individual lots generally are too small, not aggregated, saddled by past environmental hazards and zoned for a prior use. To be competitive for economic opportunities, the city needs a portfolio of larger aggregated sites, remediated of environmental hazards, and ready to be marketed.”

END