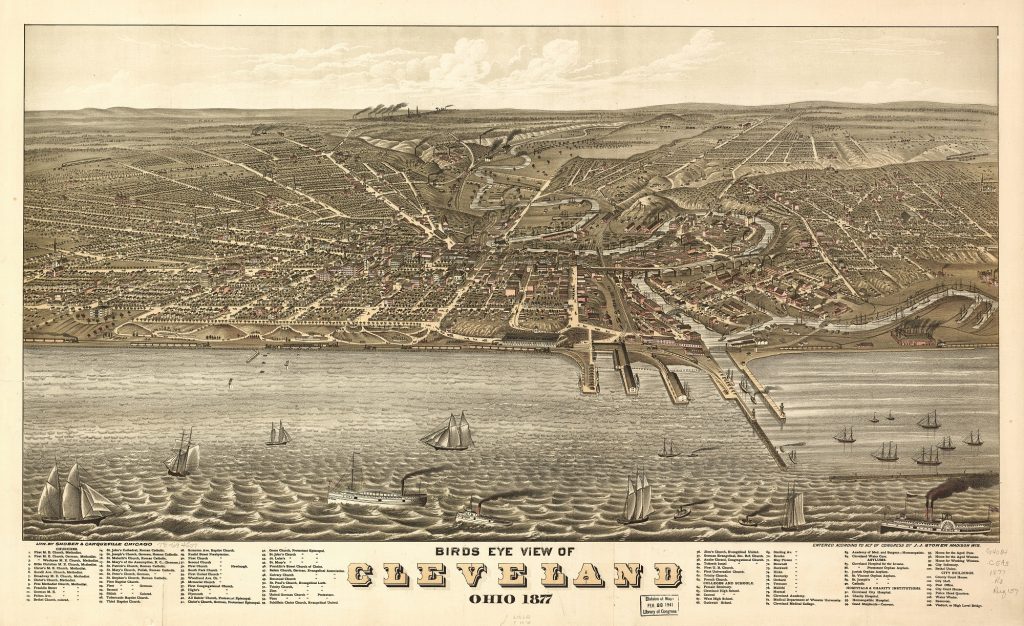

In the late 1800s, railroad tracks were the last things you cross before getting your feet wet in Lake Erie. That was before hundreds of acres of new lakefront land near Downtown Cleveland was created with landfill. Cleveland was one of the few major Great Lakes cities to have a busy mainline railroad along its lakefront. Today, it is the only one where freight trains are the dominant user of those lakefront tracks (Shober & Carqueville, Library of Congress). CLICK IMAGES TO ENLARGE THEM.

And our lakefront would be better without it

A COMMENTARY

When looking at Chicago’s enviable lakefront, it never had it. Toronto’s did, but not anymore. Same with Milwaukee’s and Hamilton’s but due to different circumstances. Detroit, Buffalo, Toledo and smaller cities like Green Bay and Erie never did. What are we talking about here? A busy mainline freight railroad routed along a major Great Lake city’s downtown waterfront.

Heavy, frequent freight train traffic is something Cleveland’s lakefront has but could do well without. But we still need to provide a steel guideway for up to 100 million gross tons of freight shipments per year to keep our region’s and nation’s economy on track.

For a study that’s now old enough to buy alcohol legally, I was hired back in 2003 to research and write a report by the Cleveland Waterfront Coalition (since succeeded by the Green Ribbon Coalition) and EcoCity Cleveland (now the Green City Blue Lake Institute). The purpose of that research was to figure out the best way to reroute as much train traffic off the lakefront as possible and to identify its benefits and costs.

The report was delivered the last time the city of Cleveland pursued a lakefront improvement plan. Then-Cleveland Planning Director Chris Ronayne, now Cuyahoga County executive, was directed by Mayor Jane Campbell to develop and implement a lakefront masterplan. That effort died upon the election of Mayor Frank Jackson in 2005, who served from 2006-2022. Now Mayor Justin Bibb is reviving calls and plans to improve the city’s long-neglected lakefront.

Lakefront freight train traffic is something that the city’s lakefront planning process so far hasn’t addressed, other than providing a more attractive way to bridge over it. The city’s next lakefront planning update will be held at 4 p.m. Aug. 5 at Mall C — the park on Lakeside Avenue between City Hall and the old Cuyahoga County courthouse.

Downtown Cleveland has had a mainline freight railroad along its lakefront east of the Cuyahoga River since the 1851 opening of the Cleveland, Painesville & Ashtabula Railroad. And it had one west of the river’s mouth since the 1853 opening of the Cleveland & Toledo Railroad which turned away from the lakefront after several miles and headed southwest to Berea. But the two didn’t connect right away for a reason still familiar to us today — concerns about blocking river traffic.

For more than two years, passengers and freight were ferried across the river between rail lines as the city of Cleveland forbade the construction of a railroad bridge at the river’s mouth. River traffic connecting lake shipping with the northern terminus of the Ohio & Erie Canal was heaviest north of old Superior Street. The only railroad bridges across the Cuyahoga River in those early years were upriver from the canal’s mouth where river traffic was far less.

Those were fixed bridges. Movable bridges for railroads were still a novel concept if for no other reason that the railroads themselves were still a novel concept. Once the railroads showed they could build a movable bridge at the river’s mouth, Cleveland officials relented. They wanted to support the growth of railroads and industry in Cleveland. But that bridge became an intolerable chokepoint as rail and river traffic grew as Cleveland grew into the 20th century.

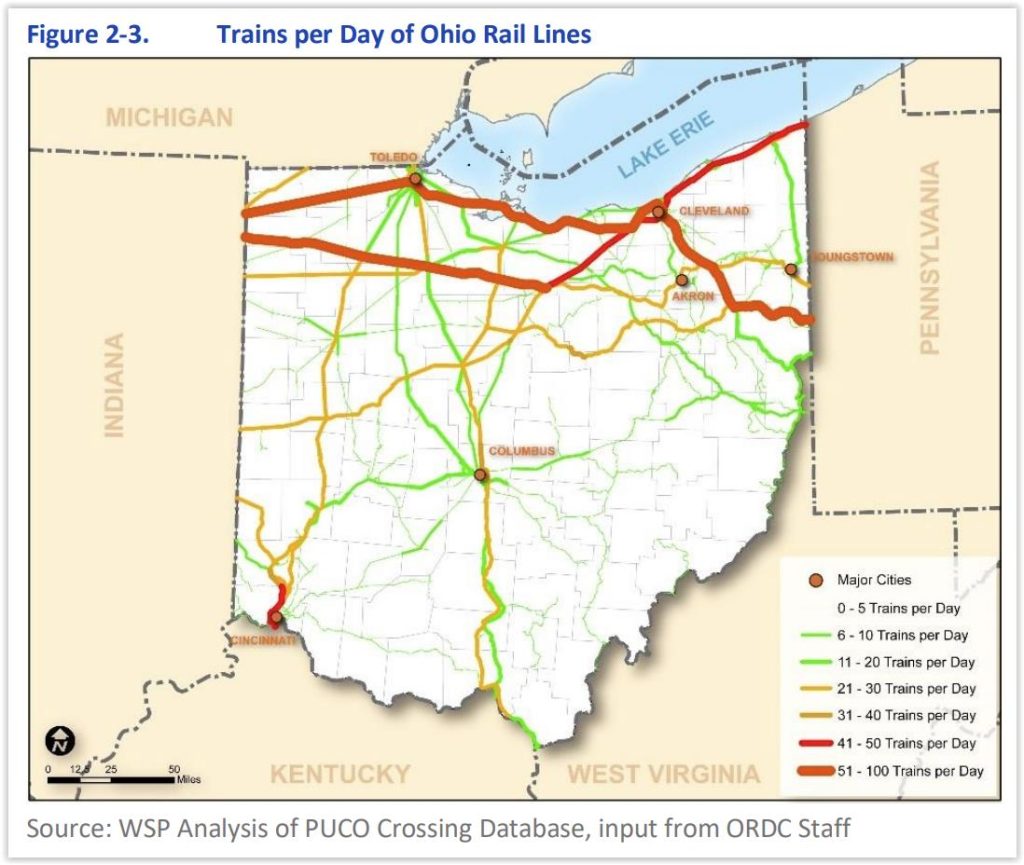

Upstream is where mainline freight train traffic should cross the river today, not just for the convenience of pleasure boating and commercial shipping, but for the benefit of Cleveland’s downtown lakefront. Depending on the condition of the nation’s economy, there are anywhere from 50-70 daily Norfolk Southern Corp. freight trains making their way across the lakefront plus four nightly Amtrak passenger trains and an occasional CSX Transportation Inc. local serving the Port of Cleveland.

Most of this rail traffic is just passing through town. The majority of trains aren’t serving the lakefront and don’t need to travel this way. Fewer than 10 trains daily serve customers along the lakefront tracks, including the passenger trains which stop at the Amtrak station, 200 Cleveland Memorial Shoreway. Most freight trains range from one to three miles long and block the river’s mouth for extended periods of time.

Yes, many of these freight trains carry hazardous materials. That includes Norfolk Southern’s Train 32N which makes the daily run from Madison, IL in suburban St. Louis to Conway, PA near Pittsburgh via Cleveland’s lakefront.

That is the same train that derailed Feb. 3, 2023 in East Palestine, OH, and caught fire, releasing harmful fumes into the air and substances into the soil and nearby streams. More than a year later, most of the town’s 4,700 residents complained of health problems.

Up until 25 years ago, this and two dozen other daily long-distance freight trains between those and other freight terminals traveled south of Greater Cleveland via Mansfield and Canton. This route via less populous parts of Ohio was downgraded four years ago, pushing a few more daily freight trains through Cleveland.

Cleveland City Council protested it in a resolution passed in 2020. Although only federal authorities have jurisdiction over interstate commerce and where it goes, local, state and federal governments can provide capital funding to provide better railroad infrastructure that encourages railroad companies to be more responsive to local issues.

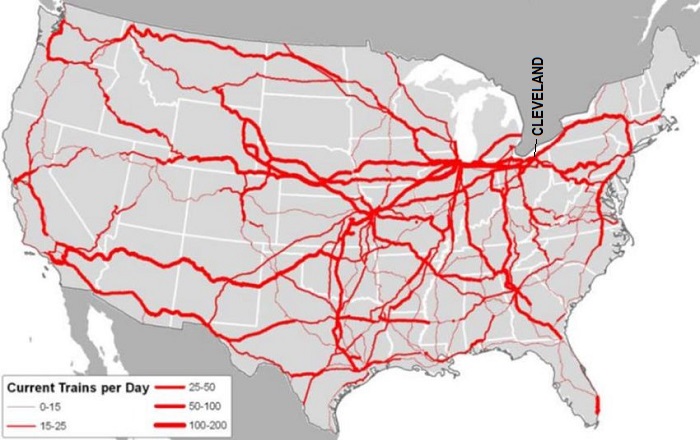

That’s a compelling factor, especially when most east-west freight rail traffic and their hazardous cargoes in the United States pass through Greater Cleveland, according to state and national rail traffic maps. Roughly half of Greater Cleveland’s freight traffic travels along Downtown Cleveland’s lakefront. If you want that to change, you have to create a path for trains to use that’s at least as good as the existing lakefront routing.

What makes for a “good” route for freight trains? A route owned or leased by the user that’s flat with gentle curves plus wide and high clearances — there are numbers that define good-better-best for those. And the track (or two on busier lines) must be constructed with seamless, heavyweight rails, on a well-drained and maintained trackbed governed by an interactive traffic control system called Positive Train Control. And the fewer at-grade crossings with roads and other railroads, the better.

Since we want Greater Cleveland’s industries and shippers to continue to be served by freight rail, we don’t want to detour all freight trains out of Greater Cleveland to less-populous routes farther south. Just those that don’t serve Greater Cleveland and are merely passing through. Those include about a half-dozen daily crude oil trains heading from the western United States to East Coast refineries.

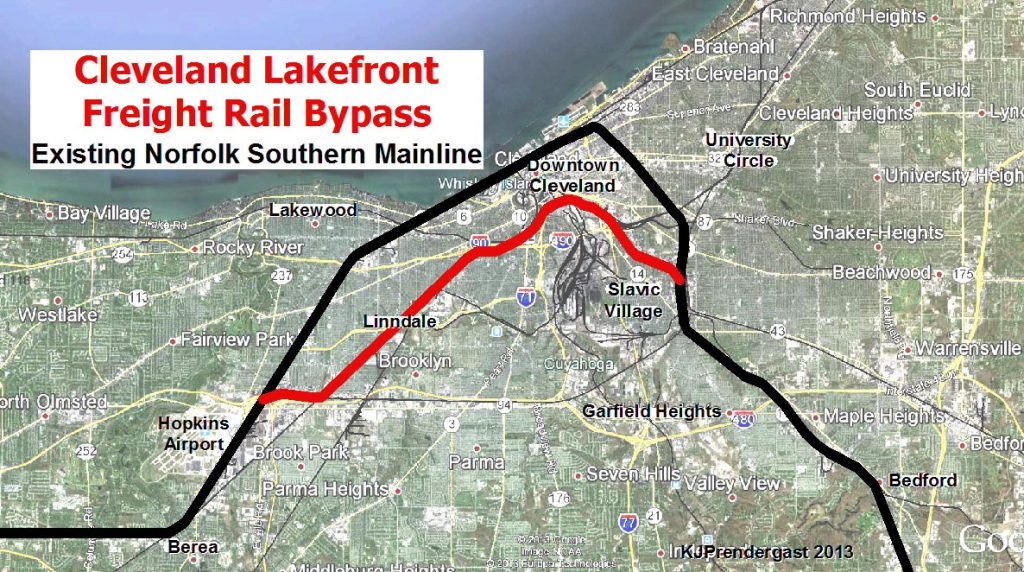

All but a few other daily freight trains should be rerouted to a new path within Greater Cleveland. That route is the same path identified in the 2003 report, dubbed the Lakefront Bypass. It detours Norfolk Southern trains that are on the lakefront to Norfolk Southern tracks that pass by on the south side of downtown and currently see fewer than 18 trains per day.

The Lakefront Bypass starts/ends on the city’s west side near Hopkins Airport and ends/starts in the North Broadway neighborhood on the city’s southeast side. It would add a third main track to most of the two-track-wide Norfolk Southern route, called the Cloggsville Connection on the west side.

That route travels around the north side of Rockport Yard that’s just north of Interstate 480, turns northeast through Linndale and along Train Avenue to near Fulton Cemetery. It crosses the Cuyahoga River on a two-track bridge about 70 feet above the water which is good. That will clear most pleasure watercraft. But it won’t clear the big ships filled with aggregates that head to Cleveland Cliffs’ steel mills and other shippers.

So it has a vertical lift span above the river as part of a 3,000-foot-long railroad bridge over the Cuyahoga Valley. A new, taller railroad bridge with three tracks and that clears the biggest ships could be built next to the existing railroad bridge but would add a major expense. But there appears to be at least 30 feet of clearance above trains that pass below the Inner Belt highway’s George V. Voinovich Bridges.

East of the Cuyahoga Valley bridge, the Lakefront Bypass would regain its third track along Norfolk Southern’s Lake Erie District tracks past the Main Post Office. Next to Interstate 77, a small amount of land would need to be acquired so the bypass can leave the Lake Erie District’s tracks and turn southeast on a two-track line that was once the Erie-Lackawanna Railroad to Youngstown and beyond.

Nowadays, this Norfolk Southern-owned right of way is leased by shortline railroad company OmniTRAX to serve local shippers out to Solon. The bypass would use this line only so far as a location known to railroaders as Erie Crossing, just north of Union Avenue. Here, rerouted Norfolk Southern freight trains would rejoin the mainline to Pittsburgh and the East Coast.

The Lakefront Bypass goes through fewer residential areas and more industrial districts than the current route which has more residential neighbors. The bypass has only one at-grade road crossing on it — East 65th Street.

It is also 3.5 miles shorter than the lakefront route but has some grades (changes in elevation) that are little bit steeper than the lakefront routing although they don’t last as long because the bypass crosses the river 60 feet higher than the lakefront route. It’s not as fast as the lakefront route because the bypass has tighter curves.

But if built out to accommodate the lakefront route’s freight traffic at a one-time construction cost of about $200 million, the Lakefront Bypass can handle it. Nearly all of the conditions present in 2003 still exist today except that freight trains are longer. A side benefit is that the bypass can free up track space via the lakefront for the expansion of passenger rail services.

The Ohio Rail Development Commission (ORDC) announced in late-June that it chose the consultant team of HDR and HNTB for the Phase I Corridor Identification Program grant-funded Service Development Planning for both the Cleveland – Columbus – Dayton – Cincinnati (3C&D) as well as the Cleveland – Toledo – Detroit Corridors. Both corridors could add a dozen additional daily passenger trains to the congested lakefront-Berea tracks.

Planning for the Lakefront Bypass could begin from these efforts. It could also start from two other efforts. One is Amtrak’s request to Congress for a Great Lakes Stations Improvement Program. The other is the city of Cleveland’s request to the U.S. Department of Transportation for $268 million in funds to develop planned improvements to the lakefront including converting the Shoreway highway into a boulevard and building the North Coast Connector land bridge.

That $268 million ask includes an $8 million request to the Federal Railroad Administration for a Consolidated Rail Infrastructure and Safety Improvements (CRISI) grant to conduct engineering and environmental clearances to be eligible federal construction funds to build a multimodal transportation center on the lakefront. If the city wins the CRISI grant, planning for the Lakefront Bypass could be spun out of that, as well.

Comparable model outcomes from this work are what Milwaukee and Toronto did to their lakefront railroads, although Toronto’s outcome was much better, in my opinion. No other major Great Lakes cities had busy mainline railroads for both freight and passenger services along their lakefronts like Milwaukee, Toronto and Cleveland. Hamilton and Buffalo’s situations were close, although I wouldn’t consider their lakefront tracks to have ever been a mainline though they used to be fairly busy.

In Milwaukee in the late-1960s, construction of Interstate 794 resulted in rerouting Chicago & North Western freight and passenger trains off its 8.3-mile line from downtown north to Fairfield. The tracks were removed, replaced with a recreational trail. A lakefront park was built on landfill on one side of the trail and a row of North Prospect residential towers on the other.

The Brew City’s freight and passenger trains were consolidated onto a route passing along the southern edge of downtown Milwaukee. That’s where the city’s multimodal transportation center is located, served by Amtrak, Greyhound, other bus services and its downtown streetcar.

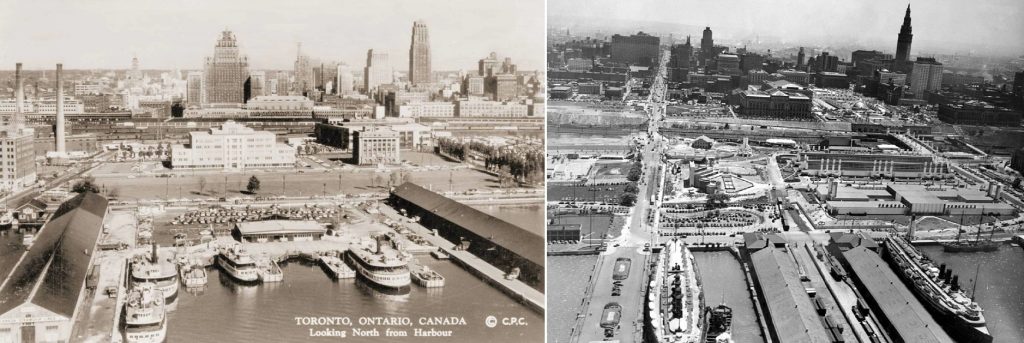

Prior to the 1960s (seen at left in the 1950s), Toronto’s lakefront was busy with freight and passenger trains. Now it’s busy with only passenger trains. Cleveland’s lakefront, at right in 1936, was busy with freight and passenger trains as well. Now it’s just busy with freight trains. Toronto’s lead is worth following (CPC, CSU).

Toronto on the other hand went bigger and better. It rerouted all through freight train traffic off its lakefront to a belt line railroad around the north side of downtown. The exception were local freight trains that served Toronto’s port and nearby manufacturers and shippers, primarily on the east side of downtown.

That left the tracks into and through downtown, including Toronto Union Station, to handle its dwindling passenger train traffic. In the 1960s, however, Toronto still had dozens of daily passenger trains, mostly long-distance runs. That changed starting in the late-1960s when lakeshore commuter trains began.

Since then, they increased in number on that and other lines to the point that Toronto Union Station is now Canada’s busiest transportation terminal, serving more than 200 trains and over 300,000 passengers on most days. That wouldn’t have been possible had the lakefront tracks still hosted dozens of daily freight trains.

Cleveland may never reach that level but, removing heavy freight train traffic off of our lakefront can get Cleveland to where Toronto was in the 1960s. Ironically, that’s when Cleveland and its metro populations were comparable to Toronto’s and Metro Toronto’s, before the economies of both urbanized regions went in opposite directions.

Because of its many urban developments, including its lakefront revitalization and transportation investments, Toronto was able to capitalize on geopolitical troubles in Quebec province and Canada’s liberalized immigration policies to become the New York City of Canada. Who knows what national and global shifts we could capitalize on if we in Cleveland decided to be a more attractive place to newcomers?

Our lakefront is our welcome mat. Let’s not keep dozens of freight trains wiping their feet across it.

END