An architect’s rendering of a mixed-use development surrounding a proposed, enclosed, 67,000-seat stadium in suburban Brook Park. The $1.2 billion in development would depend on the $2.4 billion stadium, which in turn would depend on half of its funding being financed by public-sector sources (HKS). CLICK IMAGES TO ENLARGE THEM.

A deal appears to be in the works

A COMMENTARY

Two years before Gloria Gaynor released her 1978 smash hit “I Will Survive” about recovering from a breakup, she released another song titled “Let’s Make a Deal” — referring to a marriage. In the coming days and weeks, we’re likely to hear more about a similar plot line albeit in reverse involving the proposed new stadium in suburban Brook Park.

This time, the two principal parties — the city of Cleveland and the Haslam Sports Group (HSG) — are faced with breaking up their football stadium partnership. In its place, so they can both move on and survive and thrive, they’re making gestures toward a deal for a new partnership based on a new purpose.

The difference in our local, contemporary example is that there are multiple parties that have stakes in this relationship. They include Cuyahoga County, State of Ohio, fans of the Cleveland Browns football team owned by HSG, and taxpayers.

From all indications, it sounds as though Cleveland Mayor Justin Bibb and Council President Blaine Griffin, as well as HSG owners Jimmy and Dee Haslam, are willing to negotiate — something. There are various rumors from well-placed sources as to what this could include. And much still depends on a very fluid situation.

The Haslams want $600 million from the state to help fill out the $1.2 billion public-sector share, or 50 percent of the $2.4 billion cost of an enclosed, all-purpose stadium in suburban Brook Park. The Haslams would secure the other half from the private sector.

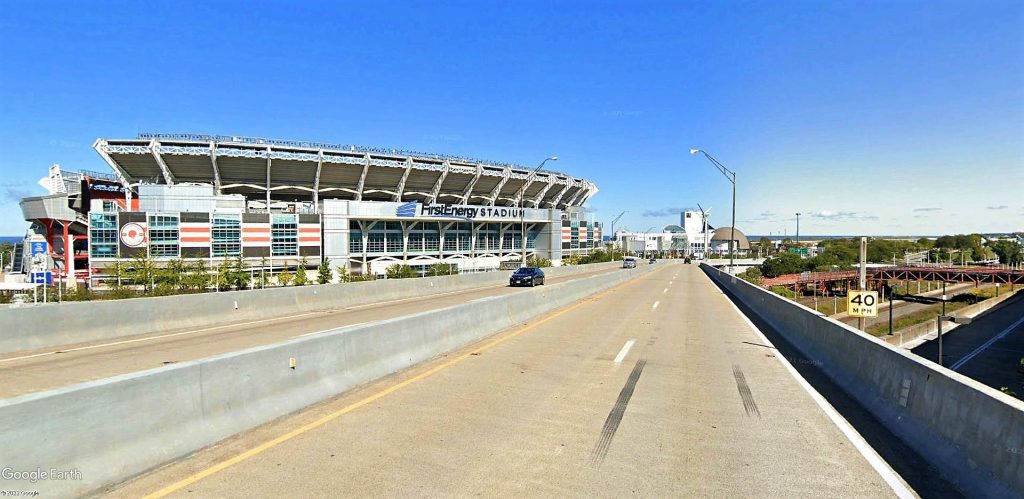

In anticipation of the state coming forward with something close to that $600 million, the city is weighing its own request to the state. In that situation, NEOtrans has learned that city officials would want to make Downtown Cleveland whole in the absence of the Browns, once its lease at city-owned Huntington Bank Field ends after the 2028 football season.

The city would make that request of the state regardless of the outcome of the Haslams’ lawsuit seeking to declare Ohio’s “Modell Law” unconstitutional. Named for former Browns owner Art Modell who took his National Football League franchise from Cleveland to Baltimore in 1995, the law restricts the owner of an Ohio-based professional sports team from uprooting a team.

Ohio Gov. Mike DeWine, who was in Cleveland in recent days to meet with Bibb and others on the stadium situation, is sensitive to supporting state funding to move a football team that might hurt Downtown Cleveland business and upset fans. This is an economic and emotional issue for many.

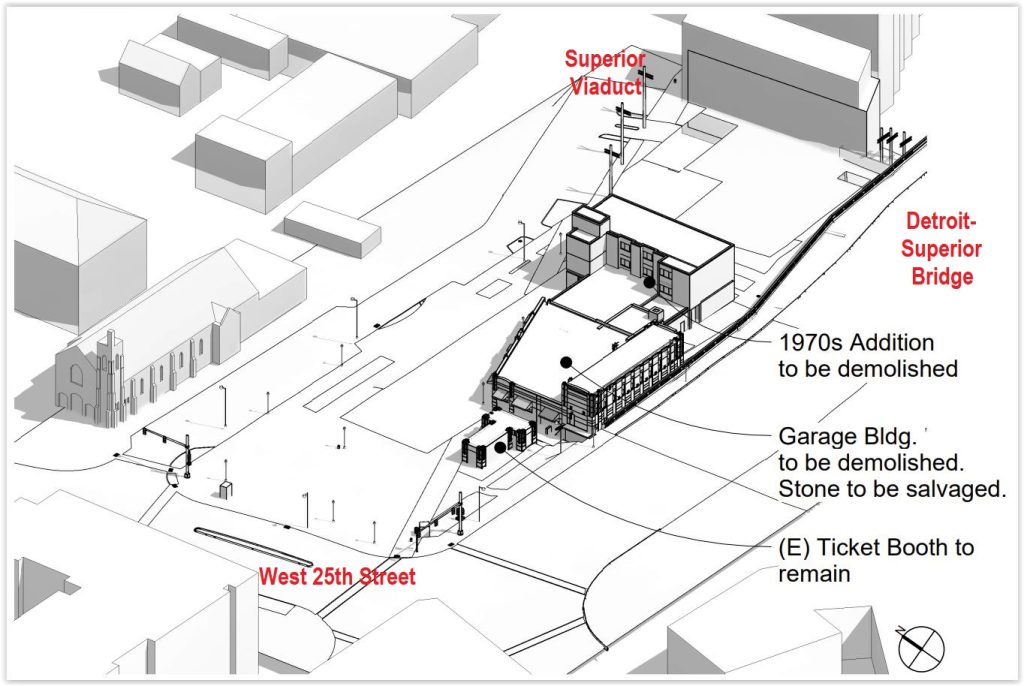

There are many pots of state money — Ohio Department of Natural Resources, Ohio Department of Development, Ohio Department of Transportation and more — that could be programmed to support the city’s lakefront plans. Those plans are being amended to look at how the 31 acres of the current Browns stadium site could be repurposed.

Meanwhile, sources close to the Browns say the Haslams are willing to deal, too. The Haslams won’t respond to “extortion” from the city, however. The city is rumored to be seeking up to $50 million to demolish the existing Browns stadium and perhaps another $100 million to help build out its lakefront redevelopment vision.

But those sources say the Haslams are willing to help fund the lakefront plan out of altruism, as part of a partnership to help improve the city’s quality of life. And a redeveloped lakefront could certainly fall into that category.

After all, it was the Haslams who suggested this current lakefront planning effort in the first place, as part of a renovated stadium. That includes a $200 million land bridge over the lakefront railroad tracks and a newly redesigned Shoreway Boulevard that won $60 million in federal funds to partially realize it.

At the same time, those who were wondering if a new Red Line rapid transit station would be built next to the Brook Park stadium site to connect it to downtown, Greater Cleveland Regional Transit Authority CEO and General Manager India Birdsong said last week there are no such plans.

The Browns said there are no plans to provide a direct pedestrian path to the planned stadium from one of the existing Rapid stations — at Brookpark Road or a Cleveland Hopkins International Airport. The latter is actually closer to the center of the stadium site as the crow flies. Apparently the Browns want to collect as much parking revenue as they can.

While Bibb said the Haslams abandoned the lakefront vision, the Haslams say they came to a realization that a $1 billion renovation of the existing stadium would add only 20-25 years to the team’s lease and would still require an additional $350 million to $500 million for capital repairs over the life of the extended lease, according to a summary leaked to NEOtrans.

City officials floated the idea of closing Burke Lakefront Airport and building a domed stadium there instead. It could also host much more stadium-area development at an amazing lakeside location. But the Haslams estimated that a Burke dome might cost upwards of $3.3 billion — if it could be built starting in 2026 or at all. Closing a designated reliever airport is very difficult to do.

The odd man out in all of this potential dealmaking is Cuyahoga County Executive Chris Ronayne. He has admirably stuck to his guns saying that taxpayers have invested a lot into downtown infrastructure and facilities. A $2.4 billion stadium and its $1.2 billion mixed-use entertainment setting in suburban Brook Park will wastefully compete with downtown, he has argued.

Ronayne, citing upcoming costly public works projects and limited county finances for anything else new, has declined to entertain conversations about the Haslams’ Brook Park plans. One source familiar with the impasse said Ronayne refused to answer the Haslams’ calls; another said he has declined to meet with them. Ronayne told NEOtrans he won’t negotiate through the media.

City and county officials have expressed concerns that the proposed Brook Park stadium and its adjacent mixed-use entertainment complex could siphon away events and hospitality business away from Downtown Cleveland while creating new costs for taxpayers. But the Haslams said they believe Greater Cleveland can draw new events and visitors from other cities (HKS).

Ronayne said recently that he was asked by the Haslams to provide $300 million in cash and $300 million in bond issuance for the Brook Park stadium. “That dog doesn’t hunt,” he replied, citing the financial risk to the county.

If Bibb, DeWine and the Haslams make progress toward a deal where it’s apparent everyone except the county is going to get something out of it, Ronayne is going to find himself in a difficult position. Clearly, Ronayne cannot spend money the county doesn’t have.

Even the county sin tax, which was expanded by voters in 1995 to support Browns stadium and assumed to play a role either in a new or renovated football stadium, is a fading resource. It has proven incapable of meeting its existing obligations at the Gateway Sports Complex, home of the Guardians’ Progressive Field and the Cavaliers Rocket Mortgage FieldHouse.

Absent creative funding solutions that have yet to be found or publicized, it is unclear how the county could be a contributing party to any dealmaking being dangled anyway. But the first rule for a politician is to keep your options open. There is no harm in talking.

As long as every party walks away with something they and their constituents can value, they will survive.

END