FirstEnergy Stadium is only 24 years old and will turn 30 just a few months after the Cleveland Browns’ lease with the city runs out at the end of the 2028 National Football League season. Where the Browns play after that will depend on a community dialogue that will take place over the next year (Google). CLICK IMAGES TO ENLARGE THEM

If community says stay at FES, will the Browns stay?

A COMMENTARY

“I stand by my sources.”

I write that after this week’s statement from Browns owners Dee and Jimmy Haslam which followed NEOtrans’ most recent article about the Browns’ desire for a new all-purpose stadium for Cleveland. At the National Football League’s (NFL) Annual Meeting, the Haslams said “They remain committed to upgrading the Browns’ stadium — with the primary goal of renovating FirstEnergy Stadium in accordance with the City of Cleveland’s plans to upgrade waterfront area between Lake Erie and downtown.”

Why do I stand by my sources? Because I know them better than the Haslams, and they’ve been right about real estate developments more often than the Haslams have been about their business of the Cleveland Browns. And furthermore, their statement wasn’t the strongest words of commitment you’ll come across. They chose their words carefully, noting that their commitment was to an upgraded Browns’ stadium regardless of whether it’s a new facility or a renovated FirstEnergy Stadium.

Yes, they say their primary goal is “In all likelihood” a renovated stadium but my sources say that’s only sort-of true. I hope you paid attention to the statement’s sub-head, below the main headline. That sub-head read “The Haslams said at the NFL Annual Meetings they remain committed to helping the City of Cleveland upgrade their waterfront property, which could include a renovation of FirstEnergy Stadium.”

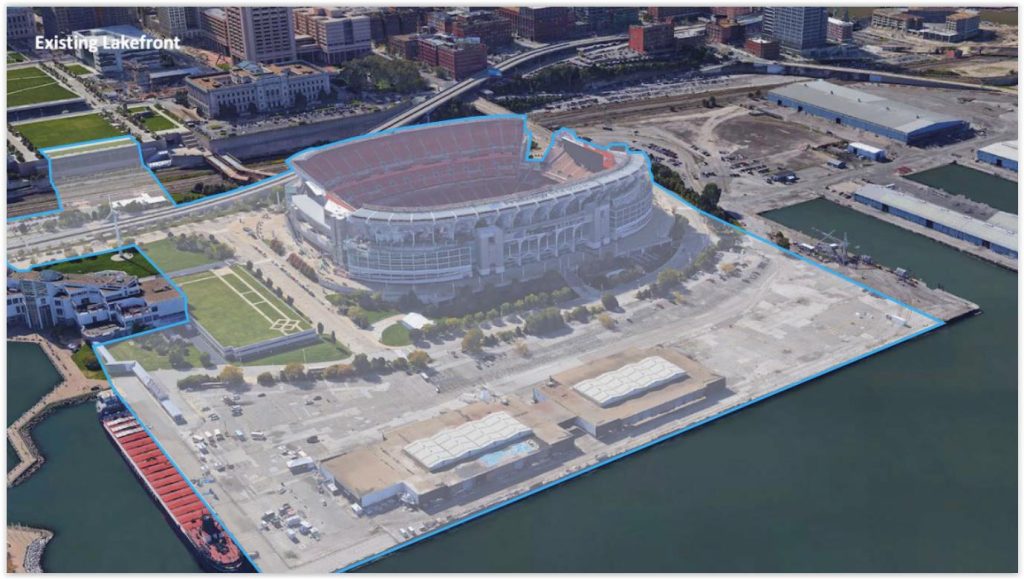

To me, that says the Haslams’ primary goal isn’t a renovated stadium, but rather an upgraded downtown Cleveland waterfront the Haslams want to develop with housing, shops, hotels and entertainment. The 50 acres surrounding the stadium is owned by the city, as is the 20 acres on which the stadium sets. That waterfront “could include” a renovated stadium, the Browns’ statement said. But it implies that it’s not essential. Indeed, I would argue that, absent a permanent roof or a movable one, having an open-air stadium on the lakefront limits its potential. A stadium that isn’t enclosed, multi-purpose and a year-round facility is not the highest and best use of waterfront land.

The Haslams addressed the possibility of adding a roof to FirstEnergy Stadium, saying “In all likelihood, it’s not going to have a dome.” That’s not surprising, considering the high cost of adding one as well as to the large amount of government red tape to get one, given the proximity of Burke Lakefront Airport and the many Federal Aviation Administration aircraft clearance restrictions that would be involved.

The site is also a landfill on reclaimed submerged lands, subject to legal ownership by the State of Ohio rather than the city of Cleveland which has been an ongoing dispute between city and state for decades. That century-old landfill isn’t stable. It’s a mix of trash and fill dirt. To stabilize it for the construction of external structures to support a new roof would require lots of legal maneuvering just to build the costly foundations. FirstEnergy Stadium itself was built on the 92-year-old foundations of the old Cleveland Municipal Stadium. Local history aficionados say those foundations were merely old utility poles driven straight down into the landfill.

Thus, if the federal, state and local regulations don’t preclude the addition of a dome or retractable roof, the ground on which FirstEnergy Stadium sets would. So, without a roof, FirstEnergy Stadium isn’t going to get used enough to become a year-round people magnet. Instead it will remain a doughnut hole of vibrancy on the waterfront. In negotiations with the city, the Haslams are reportedly putting it on the city to say publicly that, if they want a waterfront that’s more active year-round, then the stadium needs to be demolished and replaced onsite, or moved inland.

The Browns already know renovation of an open-air stadium that was poorly designed, quickly built and not easily or cheaply remedied is not the ideal situation. Over the next year, the Browns will have a conversation with the community on what to do about it. Renovation will involve greater compromises than a new stadium. Those compromises may be acceptable to city officials and the general public. We don’t yet know if the compromises will be acceptable to the Browns. Will any compromises by the community cause it to gain buy-in of a new stadium or will a lack of compromise cause the Browns to leave Cleveland — again?

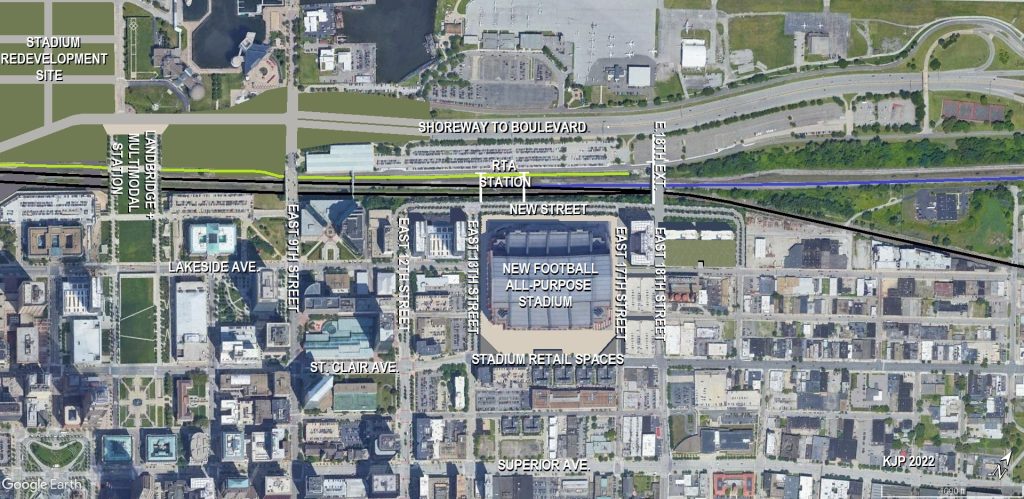

The Browns are counting on the public to catch up to where they are on a desire for a new stadium through the natural progression of civic conversations. The Browns want the city and the public to take ownership of the idea that the existing stadium cannot be renovated to provide enough community and waterfront benefits or to endure structurally for another 20-30 years. And, of course, even without a retractable roof, the stadium will still lack sufficient concourse spaces. The space needed to widen the concourses will diminish after the Shoreway bridge is removed in favor of a boulevard past FirstEnergy Stadium’s front door so a new downtown-waterfront land bridge over the busy railroad tracks can be built.

“There’s a lot of infrastructure that has to go into connecting downtown, which is the first thing that has to happen,” Jimmy Haslam said. “We’ve got to connect downtown to the waterfront, right? Everybody knows that. So you’ve got to relocate the highway … I do think the city, the county and the state are working together well, but there’s a lot of hoops to jump through.”

Over the next year, as the Browns gather community input, they are hoping the community comes to the same conclusion they have: that FirstEnergy Stadium constrains, and is constrained by the very things needed to make downtown’s waterfront more of a year-round destination.

“I think it’s a year-long phase,” Dee Haslam said. “We’re hoping to help out in any way we can. It’s a long process, but I think they’re doing it right because they (the city) want to make sure they have a lot of community input on how it works and what the community wants.”

Also, watch the Browns test-market some features that could go into a renovated stadium, but are more likely to appear in a spacious new stadium. Those things include new premium seating and new, fan-friendly amenities that cannot be added in abundance in FirstEnergy Stadium’s space-constrained concourses. They will appear with on-site staff asking questions and others sending out surveys to fans who have tried these new features to determine what the Haslam Sports Group will put into the design of their new stadium.

That’s just part of what the Haslams want. They also want an expanded headquarters and practice facility in Berea. The city of Berea and three affiliates of the Haslam Sports Group — SAM Enterprises LLC, SAM Enterprises I LLC and Rental Acquisitions LLC — have spent the last five years acquiring nearly 9 acres of land west of the existing Browns facility which is on 18 acres city-owned land at 76 Lou Groza Blvd. The property acquisitions extend to Front Street and beyond, to across Depot Street from The Berea Depot restaurant, suggesting that spin-off developments such as a hotel, conference center and sports-themed restaurants and shops may also be in the offing.

By this time next year, after more dialogue, the Haslams want enough of the general public and especially the voting public to stop compromising with their waterfront and turn away from the idea of a renovated FirstEnergy Stadium. We found out too late in 1995 that then-Browns owner Art Modell didn’t want a renovated stadium either. He publicly said he supported a renovated Municipal Stadium right up until Nov. 6, 1995 when he announced he was moving the team.

If he wanted the community to buy into a new stadium, he got it. The next day, Cuyahoga County voters voted to extend a “sin tax” for 10 years by a 70-30 margin to help finance a football stadium for an expansion team that would wear the Browns name and colors. It was a big piece of the funding puzzle to build FirstEnergy Stadium. Modell later said if the city had offered that instead of a renovated Municipal Stadium, he wouldn’t have left for Baltimore. We’ll never know what the truth was from that painful time that this and other lifelong Browns fans experienced. But its repetition can be avoided if the Haslams and the city and the county are honest and open about their respective goals and expectations.

The ultimate negotiation the Browns, the city and the county will face will be with their fans and constituents. Be honest with them and they will reward you. Betray them and they will write your history for you long after you’re gone.

END