The 1970s weren’t kind to America’s older cities. The white middle class fled from them, taking their homes and jobs to the suburbs. Left behind were low-income minorities, shuttered factories and stores, hopelessness, drugs and crime.

Cleveland suffered greatly, losing more residents in the 1970s than any other decade. But Cleveland was far from alone.

America’s greatest city, New York, was a media darling for urban decline in the 1970s. Some considered New York City beyond saving, even suggesting Manhattan be turned into a prison island, inspiring the 1981 movie “Escape From New York.”

Another movie came out that same year which is relevant to recent real estate news here in Cleveland. That movie was “Fort Apache, The Bronx” starring Shaker Heights native Paul Newman.

The movie is set at a real location, the New York Police Department’s 41st Precinct building in the South Bronx. Through the 1960s and into the 1970s, the precinct offices stood as the neighborhood around it fell. It became a safe haven from a neighborhood that police considered hostile.

The 41st Precinct earned the nickname “Fort Apache” from the 19th-century U.S. cavalry outpost on Native American lands depicted in the 1948 movie starring John Wayne and Henry Fonda. In the film, the Army and the Apaches battled but the Army could always retreat to their lonely but safe outpost on America’s western prairie.

In the 1970s, one-third of the Bronx’s population had moved out. Desperate landlords hired mobsters to burn down their apartment buildings and influence the investigations so that they could collect insurance money. Looking out the windows of the 41st Precinct revealed the crumbling shells of apartment buildings and businesses.

The rubble of abandoned cities and the sometimes violent desperation among those left behind is how many neighborhoods in Midwest and Northeast cities earned the tag “War Zones.”

Few places in Cleveland earned that tag so well as its Kinsman neighborhood. East of East 55th and going uphill toward Mount Pleasant, this was a district of worker housing for newly arrived European immigrants to work in factories and on the railroads.

It was a smoky, polluted area, sandwiched between the Nickel Plate Road’s East 55th railyard and the Pennsylvania Railroad’s Kinsman Yard. Those railyards attracted hobos during the Great Depression.

And the area became the dumping ground for many of the Torso Murderer’s dismembered victims in the 1930s. Kinsman was where city Safety Director Eliot Ness burned down shanty towns, hoping to scare off the Torso Murderer.

Among the least desirable Cleveland neighborhoods to flee during the post-war era of “White Flight,” Kinsman was near the top of the list. Of course, poor minorities left behind tend to flee as well, often to the nearest intact neighborhood. The cycle of decline, blight and abandonment was set into motion, chasing hope and the feeling middle class farther and farther out from the city’s older geographic center.

With urban sprawl, the metropolitan area grows outward without a corresponding increase in metro area population. The Greater Cleveland-Akron metro population has been stuck at about 2.8 million since 1960.

Sprawl ripped open a gaping hole near the metropolitan area’s geographic center, commonly called the “Urban Doughnut Hole.” Cleveland’s doughnut hole today includes more than a dozen square miles of the near-east side, creating urban prairies. Those prairies, although much smaller, are as desolate as the prairies portrayed in “Fort Apache” and the rubble of buildings near “Fort Apache, The Bronx.”

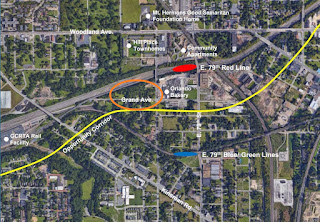

The southeast-angled alignment of Kinsman Avenue and the urban prairie around it helped the area earn the name “The Forgotten Triangle.”

Through it run two high-capacity rapid transit lines, each featuring stations at East 79th Street although several blocks apart. They are among the least-used rail stations in the Greater Cleveland Regional Transit Authority (GCRTA) system. Alongside are fields and overgrowth where 19th-century factories stood but closed 40 years ago.

|

| A rendering of what the Opportunity Corridor could look like through Cleveland’s Forgotten Triangle (ODOT). |

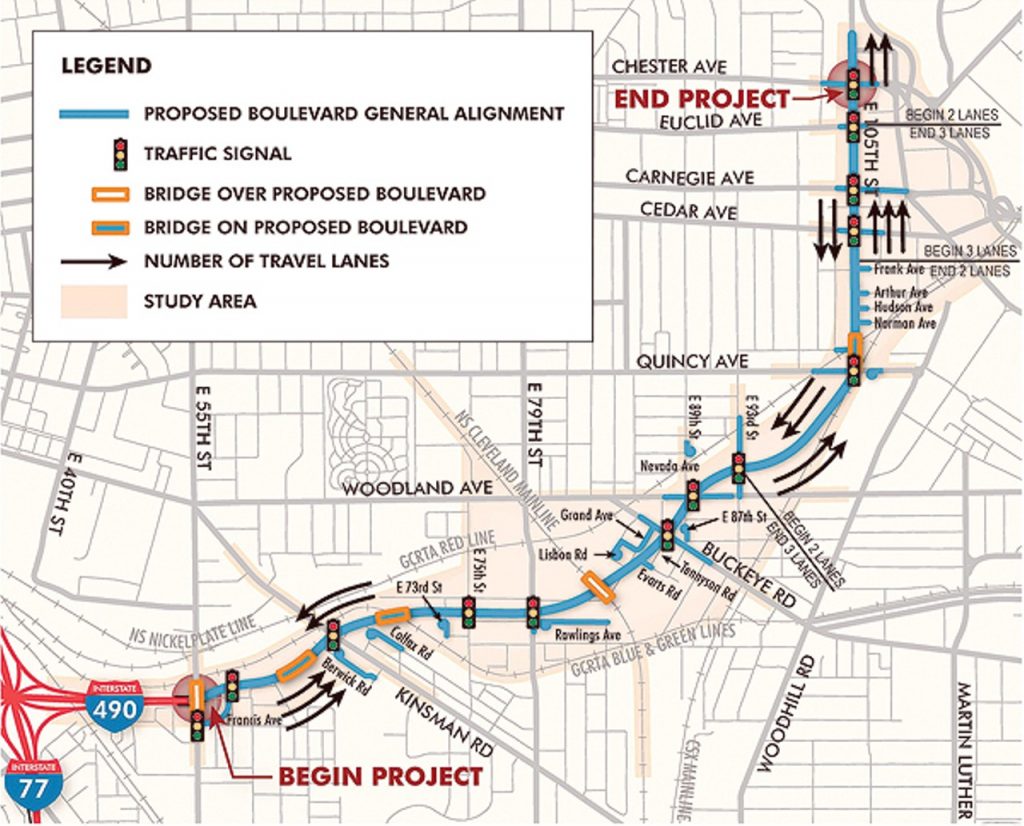

And it is where the Ohio Department of Transportation (ODOT) is building its $350 million Opportunity Corridor boulevard to link Interstate 490 with booming University Circle — Ohio’s fourth-largest employment district.

Just up the tracks of GCRTA’s Red Line in both directions, developers are squeezing luxury apartments and condo buildings within a short walk of stations in Little Italy, Downtown and Ohio City. Those areas avoided the decline of the Forgotten Triangle. They retained a community, a foundation on which to build. We began to rediscover why humanity had liked cities for 5,000 years.

This area is an empty slate. It’s a chance to go SIM City here.

So while developers are encountering increasing resistance from NIMBY’s in hot areas like Little Italy and Ohio City, the Forgotten Triangle remains the ultimate doughnut hole that needs be filled to counter sprawl. But there’s no momentum here. No private developer wants to build a Fort Apache in this urban prairie.

So the city decided to do it. Ironically, it is doing so with a police presence — much like the Bronx’s 41st Precinct. Except this police presence its much larger and includes a large amount of “civilian” employment — database managers, accountants, human resources staff, purchasing managers, secretaries, etc.

| Conceptual rendering of the new Red Line rail station at East 79th Street, for which construction is scheduled to start in 2020 and be completed a year later (GCRTA). |

On Nov. 14, city officials announced it would build a new Cleveland Police Department (CPD) headquarters at East 75th Street and Grand Avenue. The location is next to where ODOT contractors are now building the Opportunity Corridor boulevard. And it is a short walk from where GCRTA will start building in 2020 a new Red Line rail station at East 79th.

City governments are responsible for determining how the land in their jurisdictions are to be used for the betterment of the community as a whole. Usually that is done through zoning. But when a city has an opportunity to help change the fortunes of a neighborhood by the location of civic facilities, it should do so.

And that’s what the city finally did with its CPD HQ after several failed attempts at locating at two other locations downtown. In the Forgotten Triangle, the city will plop down amid new transportation facilities nearly 700 jobs, relocated from the corner of Ontario Street and St. Clair Avenue.

There will also be many visitors to the CPD HQ including those researching and requesting copies of police records, suppliers doing business with the CPD, as well as witnesses, lawyers and accused criminals meeting with police.

There will also likely be lots of travel between the CPD HQ and the Cuyahoga County Jail. The latter is also the subject of a site location analysis by the county. With the city choosing the intersection of East 75th and the Opportunity Corridor as the site for its CPD HQ, it may also influence the county of where it might eventually put its new Consolidated Jail Facility.

On April Fools Day of this year, I joked that the county would build its new jail as glassy high-rises on the Opportunity Corridor. But that attempt at humor might prove to be true, and that’s possibly not a bad thing.

If the new roadway was called anything else, it’s doubtful that anyone would raise their eyebrows at putting a jail on the cheap, vast open lands along the Opportunity Corridor. There already is a jail along this new boulevard — the Cuyahoga County Juvenile Detention Center between Quincy Avenue and the Red Line tracks.

The key to whether or how the new CPD HQ might spark some development momentum depends on the design of the new facilities, possibly totaling nearly 500,000 square feet when parking is included.

For example, in 2010, the Cuyahoga Metropolitan Housing Authority (CMHA) built its new headquarters and storage/garage totaling 92,158 square feet at Kinsman and East 80th. The building is a bunker. It is dead at street level because it has no pedestrian permeability along the sidewalks.

Nor are there any ancillary public uses like a sidewalk cafe or a bank or a job training center offering pedestrian access from the sidewalk — just the ubiquitous Cleveland grassy moat encircling this modern, public building.

Pedestrians, with their eyes on the street scene, make an area feel safer and more vibrant. The lack of them is no surprise why the CMHA had little spin-off benefit for the immediately surrounding neighborhood, despite placing several hundred jobs on Kinsman.

Nine years later, it took the stewardship of the Burten Bell Carr (BBC) community development corporation to spur construction of a supportive development across Kinsman from CMHA. Construction began earlier this year on the Box Spot Open Air Market where visitors can shop at small businesses and eat foods grown by the neighborhood’s many urban farms and gardens.

But the CPD HQ will have more workers and more people coming and going 24 hours a day than CMHA. If it isn’t built like a bunker, it offers the opportunity for more cafes, restaurants and shops in the surrounding area — preferably placed as ground-floor uses in new residential or commercial buildings. Those ground-floor public uses can also serve employees at the nearby Orlando Baking Co., Federal Equipment Co., Techceuticals and the Miceli Dairy Products Co.

And they can also provide a foundation for more housing planned by BBC as well as by private developers. With few restaurants or retail for miles, developers would be hard-pressed to justify taking a risk by building in the Forgotten Triangle. The CPD HQ can change that desolation.

Indeed, in New York’s South Bronx, the 41st Precinct building was renovated in the 1990s by the city as an office building for detectives. That commitment by the city supported a revival of its neighborhood, replacing burnt-out shells of apartment buildings with new housing, cafes and shops to support a diverse, working-class neighborhood.

Hopefully that will be the long-term outcome of Cleveland’s new police headquarters as well.

END