Sliced in half by a freeway nearly 70 years ago, Cleveland’s Gordon Park and its surrounding area were recently dubbed by east-side real estate developers as a potential “Edgewater East.” It could be that and more depending on the results of two separate but related planning efforts that got underway last week.

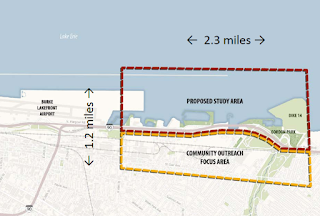

The first is a multi-agency effort led by the Cleveland Metroparks called the Cleveland Harbor Eastern Embayment Resilience Study (CHEERS). Its goal is to accommodate dredge disposal, create additional aquatic and terrestrial habitat, protect existing highway infrastructure and enhance the lakeshore from near the east end of Burke Lakefront Airport to Dike 14 at Gordon Park as a dynamic community asset.

A $125,000 grant was recently awarded to the Metroparks by the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation (NFWF) to cover nearly half of the $251,000 cost of the CHEERS plan. The Metroparks, Ohio Department of Transportation (ODOT), Cleveland-Cuyahoga County Port Authority, Ohio Department of Natural Resources (ODNR) Office of Coastal Management and City of Cleveland each pledged $25,200 as their matching shares.

The Northeast Ohio Areawide Coordinating Agency (NOACA) and Cuyahoga County Soil and Water have agreed to participate in the project. Additionally, Doan Brook Watershed Partners and the Trust for Public Land are non-profit organizations that will contribute expertise to the CHEERS plan.

“We just officially kicked off the project on Tuesday (May 26) and are preparing for community outreach next month (June),” said Metroparks Chief Planning and Design Officer Sean McDermott.

|

| The Cleveland Metroparks’ the Cleveland Harbor Eastern Embayment Resilience Study will address the area as shown in this graphic (Cleveland Metroparks). |

He noted that the Metroparks has hired WRT Design, which specializes in recreational and adaptive re-use plans, to be its CHEERS project consultant.

The second project development plan, also engaging several public entities, is being led by ODOT. It will consider alternatives, impacts and benefits involving the protection, reinforcement or realignment of the right of way of Interstate 90 in the same area as the CHEERS plan.

ODOT’s plan is being driven by an increasingly pressing problem — damage being done to I-90’s infrastructure by its proximity to Lake Erie. This situation is most critical on the section that was built around FirstEnergy’s Lake Shore Power Station. The transcontinental highway averages 160,000-plus vehicles a day on this section yet is separated from the inland sea’s pounding waves by only a skinny bike path.

That section took a beating from 20-foot-high waves during Superstorm Sandy in the fall of 2012, and it continues to be slammed by storms whose damage is made worse by record high lake water levels in recent years. Due to climate change, water levels are forecast to potentially rise higher.

“ODOT has had issues with wave action splashing onto I-90,” said Brent Kovacs, ODOT District 12 Public Information Officer. “One of ODOT?s goals of the CHEERS study is to lessen this wave action.”

That may have been aided by FirstEnergy’s removal of its Lake Shore Power Station which was built in 1911 and closed in 2015. The coal-powered electricity generating plant was razed in 2017 and most of the plant’s land was transferred to FirstEnergy spin-off Energy Harbor earlier this year, said Tricia Ingraham, a FirstEnergy spokeswoman. With the power plant gone, there’s no longer a reason for the highway to be routed so close to the sometimes angry lake.

That doesn’t automatically mean that I-90 will be moved. The highway could be protected from the lake by filling and expanding the shoreline with deposits from never-ending dredging of the Cleveland harbor and Cuyahoga River to maintain sufficient draft for big ships. Or both options could be used to spare I-90 from Lake Erie’s wrath.

“This is something that we have started to look into but is different from the CHEERS study,” ODOT’s Kovacs said. “The project team is very respectful of the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation grant application and award.”

But the only option that protects the highway from Lake Erie and reunites the two halves of Gordon Park is to move the highway.

“We have proposed moving I-90 south to reconnect Gordon Park,” said Dick Clough, executive board chair of the Green Ribbon Coalition, Inc. “It makes sense. The freeway swung north to go around the Lake Shore Power Station. Now that it’s gone, the freeway could be relocated.”

Under a number of scenarios proposed by the coalition, the highway would be realigned over the land where the power station stood. In addition to pollutants left by the coal-fired power plant, there are water intake canals and concrete-lined wastewater ponds. However FirstEnergy undertook environmental remediation of the site after the power station was razed.

Clough said the site preparation costs don’t lend to private redevelopment of the power station land. But the land south of a relocated highway, especially as you get closer to East 55th, does. That land is elevated above the highway, providing great views of an expanded Gordon Park and the lake — much like what Battery Park, The Edison and other developments offer south of Edgewater Park.

“That makes for awesome development potential,” Clough said.

Kovacs said it was too early in the planning process to know if ODOT would acquire the former power plant site. That was echoed by Ingraham at FirstEnergy which still owns a small parcel of land just north of the CSX Transportation Inc. railroad and on the west side of East 72nd Street for an electrical substation plus support buildings. She emphasized that FirstEnergy would not sell that property because the substation is an essential component of the power grid.

FirstEnergy conducted a site re-use report at the request of the city several years ago when the utility sought approvals to demolish the Lake Shore Power Station. The plant included its 306-foot-tall brick and concrete smokestack and 170-foot-tall boiler house.

Although most of the power station is gone and Energy Harbor now owns most of the former power station’s land, there is a small, yet critical and active piece of electrical grid infrastructure remaining on it, too.

Energy Harbor has voltage regulating equipment located immediately west of FirstEnergy’s remaining parcel and it was expected to be untouched in all of the power station property re-use options envisioned by FirstEnergy. An Energy Harbor spokesperson could not be located for comment.

The former power station property measures 53 acres. But FirstEnergy’s report considered that only 40 acres would be developable due to steep slopes on the site. The remaining high-voltage infrastructure and the land’s steep, 40-50 foot drop toward the lake also provides some guidance as to how far south the highway might be rerouted.

On the other hand, the area to the west of the utilities’ equipment could be redeveloped with new residential and commercial structures up to 115 feet high (about 11 stories), according to existing zoning. This acknowledges the site’s proximity to Burke Lakefront Airport. Federal Aviation Administration regulations restrict building heights to 250 feet between 4,000 and 10,000 feet from the end of a runway and near its flight path, the FirstEnergy report noted.

| Potential redevelopment concepts for the former FirstEnergy Lake Shore Power Station site assuming that Interstate 90 is moved away from the Lake Erie shoreline (FirstEnergy). |

Chris Ronayne, now president of University Circle Inc. and a port authority board member, was Cleveland’s planning director two decades ago when he led the formation of the most recent citywide lakefront development masterplan.

“The idea to set back I-90 to the tracks was offered 20 years ago with a concept plan called ‘Reclaiming our Lakefront’,” he said. “It was a good idea then and an even better idea now. ODOT was not as willing to explore the possibility of it during our subsequent planning work on the Cleveland Waterfront District Plan. But we should channel their enthusiasm and openness to the idea now. The resurgence of Gordon Park at the water’s edge, thanks to Metroparks, has increased Clevelanders’ appetite for more lakefront parks.”

The area to the north of the highway, opened up by a southerly relocation of I-90, could increase Gordon Park’s land area from 105 acres to 158 acres — not including the Cleveland Lakefront Nature Preserve, formerly a dredging disposal site called Dike 14.

The lakefront between Burke and Gordon Park, which is the subject of the CHEERS study, is a mix of marinas leased from the Metroparks which, in turn, leases them from the city. There are also some new residential developments there including the Shoreline Apartments, an adaptive reuse of the Nicholson Terminal, and the new-construction Shoreline Phase II.

But the tallest structure along this portion of the lakefront is another former power station, this one belonging to Cleveland Public Power (CPP). Originally built in 1914 as the Cleveland Municipal Light Plant, it is well-known for its “Song of the Whales” mural that greets I-90 motorists coming into downtown.

The once-coal-fired, 57,552-square-foot power station is now used as a CPP warehouse and was expanded by 16,500 square feet in 2009. There also is an electrical substation on-site. The city-owned Kirtland Pump Station and Kirtland Park are on the south side of the highway, opposite of the CPP property.

Although CPP officials have made no pronouncements about the future of this site, the Green Ribbon Coalition said they believe that this property’s inclusion in the CHEERS plan suggests it could be re-used as a result of it. Typically, public agencies don’t presume to include another public agency’s property in their land-use plans unless there have at least been some informal conversations beforehand.

The CHEERS plan community outreach focus area extends south to St. Clair Avenue. One of the goals of the study is to improve and increase the number of lakefront access routes for vehicles, pedestrians and bikes from south of I-90 and the CSX railroad. A similar effort to improve and increase access routes from south of the Shoreway and a parallel railroad was undertaken with the Metroparks’ Edgewater Park in the 2010s.

“The area north of I-90 is the main focus of the CHEERS study,” said Kelly Coffman, senior strategic park planner at the Metroparks. “The area south of I-90 is the community outreach focus area. The partners intend to engage with a wide range of stakeholders and the public, however we’re especially interested in hearing from nearby residents about what they’d like to see along Lake Erie and how the partners can improve access to park space.”

The CHEERS study is expected to take about a year. There is no timeline yet for the parallel ODOT planning effort. However, the average time it takes for a federally funded, major transportation project to go from idea to ribbon cutting is about 10 years.

END

Comments are closed.