Lots of pieces are coming into place that could greatly impact downtown Cleveland’s lakefront in a very positive way. There are many challenges to be sure, but it seems that the planets are aligning for good things to happen.

These good things center on three basic ingredients — trains/transit, shipping and development.

First ingredient — Let’s talk about lakefront development. There is a rumor going around that the Haslam Family (owner of the Cleveland Browns) want to build or rebuild a new multi-purpose stadium by the time the Browns’ First Energy Stadium lease with the city expires in 2029.

There are several sites being considered for a new stadium, with the least problematic being the former Intermodal Yards site on the other side of Interstate 90 from Progressive Field. Norfolk Southern Corp. had its truck-to-train intermodal yard here until 2001 when it moved to a larger site in Maple Heights.

Today, the 48 acres next to downtown is owned by the Ohio Department of Transportation. While the site has been rumored for use as a professional soccer stadium, it could potentially be used for both soccer and football, as well as other functions especially if it is built with a dome or retractable roof.

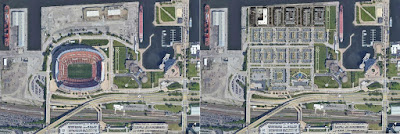

Word is that the Haslam Family wants to develop the lakefront site and use the revenues from it to help finance the construction of a new stadium or even reconstruction of the existing stadium. The stadium is a dead zone 355 days a year.

If the stadium is razed, it could be replaced with 38 acres of mid-rise housing, offices, restaurants and shops next to a publicly accessible waterfront promenade. If the stadium is reconstructed with a roof, the 18 acres of land north of it could still offer a significant development.

The timing is perfect as Congress and the Biden Administration are considering a $10 billion program to remove or at least de-emphasize some divisive urban highways and reconnect the fabric of urban centers and neighborhoods.

That could offer more funding to convert the Shoreway highway downtown into a boulevard, as has been long-planned by city officials. Another lakefront barrier, the railroad tracks, may be the subject of a land bridge to better unite the lakefront with downtown. A similar but larger project called the Rail Deck Park is planned in Toronto.

Second ingredient — Speaking of trains, Amtrak is reaching out to state and local leaders to notify them of their desire to start five new routes in Ohio. Four of them would end in Cleveland, making the city a mini-hub for up to two dozen trains per day.

Proposed routes include Cleveland to Toledo, Detroit and Chicago, Cleveland to Pittsburgh, Philadelphia and New York City, Cleveland to Buffalo, Rochester, Albany and New York City, and Cleveland to Columbus, Dayton and Cincinnati (3C Corridor).

At the outset, most trains would operate at 79 mph although they would travel at 110 mph in Michigan, New York and Pennsylvania thanks to their state-led infrastructure investments. A decade ago, Ohio gave back $400 million in federal funds to start the 3C Corridor because of false concerns that the trains would be too slow or that Ohio would have to subsidize the trains at a paltry $17 million per year.

The timing is perfect for two reasons. First, Amtrak, Congress and the Biden Administration may pass by spring a new rail development program that supports Amtrak rather than states to pay for new routes. That includes 100 percent of the construction costs and, for the first two years, 100 percent of the operating costs. Amtrak’s share would diminish each year until the sixth year when the new route matures and becomes the state’s responsibility.

Second, CSX Transportation, which owns the Columbus-Cleveland tracks, has rerouted freight traffic off the south half of the route, south of Galion. CSX may be willing to sell that part of the line, opening up an opportunity to upgrade it to 110 mph or even faster for passenger trains. The Commonwealth of Virginia is acquiring active and inactive CSX routes to develop 79-110 mph train services on multiple travel corridors around the state.

When there’s no pandemic, Amtrak puts four trains a night and more than 600,000 riders each year through Cleveland. To put that passenger count into context, this equates to more than a dozen sold-out Boeing 737s coming to or through downtown Cleveland on average, every day — er, night.

That’s just two middle-of-the-night routes. Now add four more routes — with daylight services. If Ohio’s General Assembly gives the Ohio Department of Transportation a green light to work with Amtrak, then I think we’re going to need a bigger train station, Cleveland.

Twenty years ago, the Greater Cleveland Regional Transit Authority (GCRTA) developed an attractive plan for a North Coast Transportation Center. Several years ago, the city restarted planning such a multimodal station with Greyhound and GCRTA included. Behind the scenes and with the Haslam Family, the city may still be planning the station as part of a land bridge over the tracks. If not, Amtrak’s plans should spur them into action.

And who knows, maybe someday GCRTA will consider extending its Waterfront Line as a Downtown Loop so it actually goes somewhere other than a parking lot. Right now, only one-third of downtown’s real estate is within a 5-minute walk of a GCRTA rail station. Depending on the route, a Downtown Loop could put anywhere from two-thirds to 90 percent of downtown’s jobs and residents within a 5-minute walk of the Rapid.

Third ingredient — Climate change is causing a world of losers but also a few winners. Cleveland could be one of the winners, but not for the reason (climate migration) that the New York Times wrote about a couple of times lately.

Instead, the opportunity comes not just from people moving up from the south, but from ships coming from the north. A recent article at The Maritime Executive wrote about the climate change opportunity for Great Lakes ports coming from the opening of shipping lanes from Asia through the Arctic Ocean.

A year-round Arctic route will cut shipping distances from Asian ports to Great Lakes and East Coast ports by thousands of miles. Consider that a Shanghai-Cleveland shipping route is more than 14,000 miles whether it is via the Suez or Panama canals. A Shanghai-Cleveland route via the Arctic could be as little as 9,200 miles, knocking a week off the transit time.

It is already physically possible to operate year-round through parts of the Arctic Ocean with ice-breaker escorts but those are costly to shippers. And low shipping rates make year-round container shipping via the Arctic impractical until costly ice-breakers are no longer needed. That could occur in only about 20 years, according to a BBC article.

That may also be true of Great Lakes shipping which is generally closed from December to March, also due to ice. Closure of shipping during winter plus the slower transit time via the St. Lawrence Seaway is a deterrent to Great Lakes container shipping. But that may soon change.

New mega-ships that can’t travel via the Panama Canal (but can via the Suez Canal) will soon be bound for a planned mega-ship container terminal at Sydney, Nova Scotia, where containers will be divvied up among smaller ships for delivery to ports on the East Coast and on the St. Lawrence Seaway-Great Lakes. That will reduce costs for consumer goods in the Great Lakes and East Coast regions.

The Cleveland-Cuyahoga County Port Authority is pioneering Great Lakes container shipping to/from Antwerp, Belgium. It is less time-consuming and costly to ship containers to Cleveland via an East Coast port like Newark, NJ, including a transfer to train or truck. Yet increased port congestion on the East Coast is making Cleveland increasingly attractive.

With a direct route to the Great Lakes and more ships crowding East Coast ports with the opening of an Arctic route, Cleveland is going to be an even more desirable destination for shipping companies. They are going to want to deliver loaded ships closer to the heart of America for distribution of containers by truck and rail to consumers.

Cleveland (metro population of 3.5 million) already has a leg up on Toronto and Chicago with its container port capabilities and experience. Eventually, Toronto (6.4 million people) and Chicago (9.7 million) are going to attract their share of container shipping.

But Cleveland could retain more than its share by further establishing itself as the mid-American gateway for containers due to its geographic location and port capabilities. Whether it can hold on to its leadership position will depend on whether it continues to improve its capabilities to handle more containers and increased transloading to truck and rail.

If it can, Cleveland may be in a great position geographically and economically in the coming decades.

END

- Michael Symon joins River Roots’ move to Flats

- Tenant ID’d for big new industrial development near Hopkins airport

- $119M Lakewood Common project goes vertical

- CWRU to renovate, expand one of its most historic buildings

- Master Chrome coming down, cleaning up

- Familiar Ohio City buildings go on sale for the first time in 143 years