Rebuilding regional historic assets like the West Side Market and its signature clock tower, developing fallow industrial land with urban riverfront housing seen at right, and construction cranes over downtown are all results from and/or causes of increased net-migration of college-educated people to Greater Cleveland (Iryna Tkachenko). CLICK IMAGES TO ENLARGE THEM.

Census data shows new migration trend

For decades, Greater Cleveland has suffered from the loss of its college-educated citizens primarily to star-studded cities on the East and West Coasts. Now, for a change, this former industrial powerhouse on the North Coast is enjoying a net in-migration of more brain than brawn. And while the region is still seeing net outmigration of those without college degrees, the results are at worst uneven.

The findings, based on the U.S. Census’ American Community Survey, were published yesterday by the New York Times for dozens of urbanized areas large, medium and small. The online version of the article “Coastal cities priced out low-wage workers; Now college graduates are leaving, too” included an interactive tool for readers to look up data for whatever U.S. urban area they wanted.

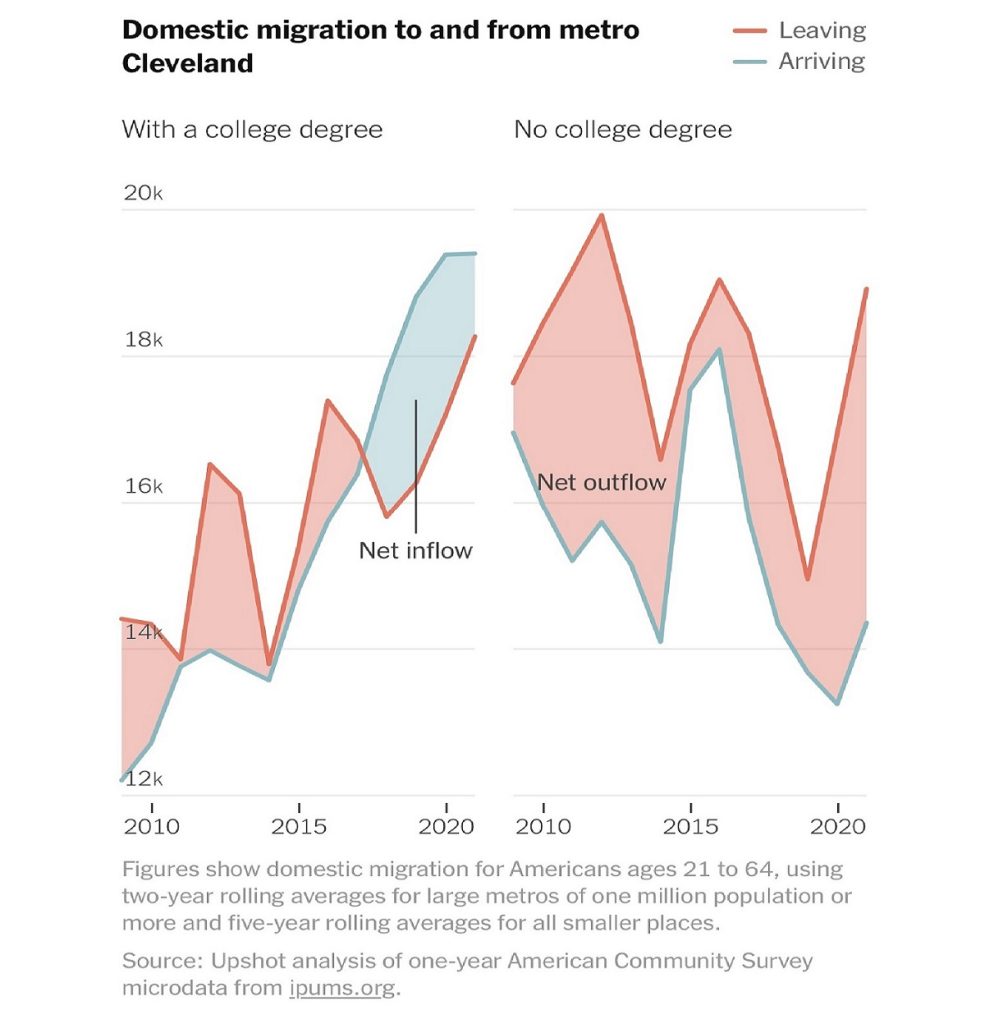

Data-based charts provided for Greater Cleveland show that, since about 2017, more people with college degrees were moving into the region than moving out. It is the kind of data that local economic development advocates have been clamoring for for many years and are finally starting to see the results of their efforts.

“The data is very encouraging,” Baiju Shah, president and CEO of the Greater Cleveland Partnership, the region’s chamber of commerce, told NEOtrans. “Cleveland has been net-gaining college graduates over the last six years. We aim to amplify this trend through the work of the Cleveland Talent Alliance. The live/work Web site launched two weeks ago and initial initiatives are being launched to further increase graduate retention and also to attract Cleveland-connected tech talent.”

Since 2017, more people with college degrees are moving into Greater Cleveland than leaving, a reversal of decades of “brain drain” into “brain gain.” The chart at left show migrations in and out of Greater Cleveland among people ages 21-64 with a college degree. The chart at right shows Greater Cleveland migrations for those without a college degree. The data also shows why Cleveland is still losing population yet seeing income tax revenues grow (NYT).

The Cleveland Talent Alliance was formed in March 2022 with an initial focus on the fast-growth sectors of IT/technology including financial services, healthcare and manufacturing, according to a written statement. Alliance members are Destination Cleveland, Greater Cleveland Partnership, Cleveland Leadership Center, Team NEO, Cuyahoga County, Engage! Cleveland, JobsOhio, Global Cleveland, MAGNET, Fund for our Economic Future, Cleveland Neighborhood Progress and the City of Cleveland.

But various indicators have been present for a while, showing that something new and positive was happening for Cleveland. Those indicators include Reddit searches of new homes in Greater Cleveland. It showed that the top four cities from which people were searching were Los Angeles, CA, Washington, DC, San Francisco, CA, and New York, NY — all metro areas with the highest costs of living. The data was from a sample of about 2 million Redfin.com users who searched for homes across more than 100 metro areas.

Also, nearly one-third of all renter inquiries into Cleveland apartment listings are coming from outside the metro area. That’s true on the for-sale side too, as realtors are finding that about 30 percent of primary-residence home sales are to out-of-town buyers. Managers of new luxury buildings like The Lumen tower in downtown Cleveland are reporting that half of their tenants are coming from outside Greater Cleveland. Charlie Gagliano, first vice president of investments at Marcus & Millichap’s Cleveland office, said those factors should help boost more apartment construction in Greater Cleveland.

“While growth markets such as Dallas, Phoenix and Charlotte have been feeling more of the effects in vacancy and slowing of rent growth, markets like Cleveland have remained far more stable,” Gagliano said in a recent interview with NEOtrans. “While we are even below a healthy level of new construction, pent-up rental demand and lack of inventory gives Cleveland and the Midwest a growing level of interest from coastal investors.”

Furthermore, in recent years, Cleveland has seen the number of available jobs grow faster than in some Sun Belt cities. Cleveland and Cuyahoga County have been gaining population among working-age adults while losing population among the elderly, the poor and families. They are being replaced by young professionals, many without children, seeking affordable housing and jobs. Cleveland’s income tax revenues have been growing strongly since the mid-2010s despite a brief, pandemic-induced drop in 2020.

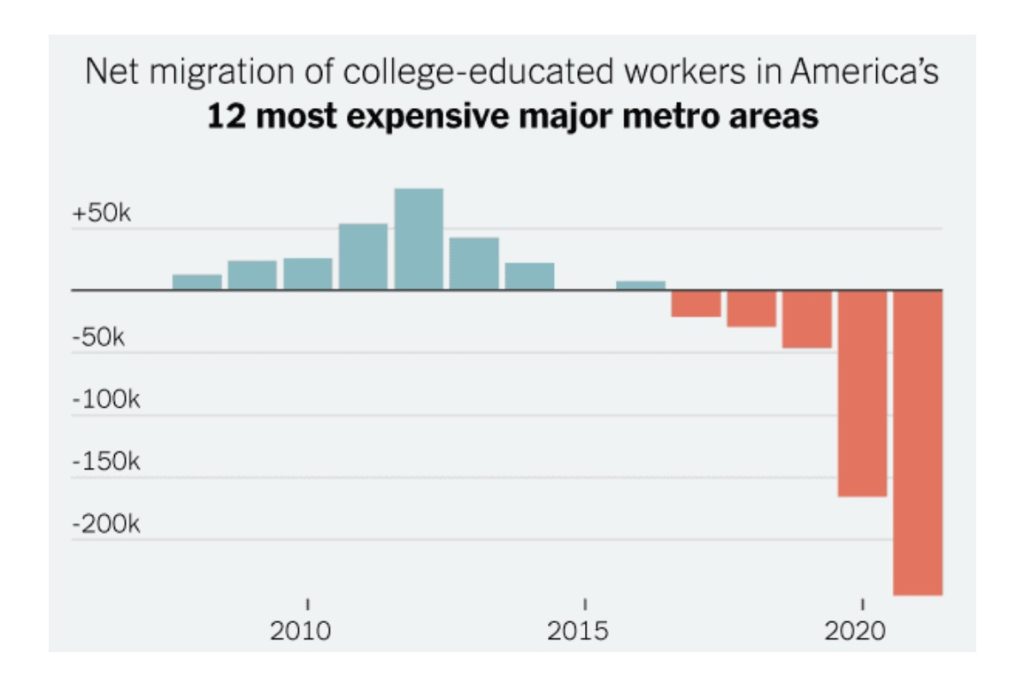

The New York Times article noted how white collar workers in cities like San Francisco, Washington DC, Seattle, Boston and Los Angeles had begun to leave in growing numbers about a decade ago. Throughout the 2010s, the departures increased but still, the arrivals outpaced them albeit at a declining rate. When the pandemic arrived, however, departures of workers with college degrees surged so sharply that these coastal star cities have lost more educated workers than have moved in.

“For most of this century, large metros with a million residents or more have received all of the net gains from college-education workers migrating around the country, at the expense of smaller places,” the article noted. “But among those large urban areas, the dozen metros with the highest living costs — nearly all of them coastal — have had a uniquely bifurcated migration pattern: as they saw net gains from college graduates, they lost large numbers of workers without degrees. At least that was true until recently. Now large, expensive metros are shedding both kinds of workers.”

There were a few outlier metro areas with more than a million people that were not seeing a net in-migration of college graduates. Greater Cleveland was among them until 2017. The article noted that, “since 2020, the workers moving in and out of the Cleveland area have been roughly evenly divided between those with and without a college degree. The region is now gaining workers with a college degree and losing those without a degree.”

END