A Cuyahoga Valley Scenic Railroad train pulls into the Rockside Station in suburban Independence. This is the farthest north the popular trains go toward Cleveland. While there is an effort underway to extend the trains north to downtown Cleveland, a legal action taken earlier this month may have significantly complicated those efforts (KJP). CLICK IMAGES TO ENLARGE THEM.

Fired director signed release of lien on rails

ARTICLE UPDATED JULY 7, 2023

While helping Bedrock Real Estate acquire land for its downtown riverfront development, the city of Cleveland may have also “significantly harmed” nascent efforts to extend Cuyahoga Valley Scenic Railroad (CVSR) passenger trains north to downtown. That harm was the apparent result of the city releasing itself from a lien on current and former railroad rights of way along the Cuyahoga River from below Tower City Center south to near Interstate 490.

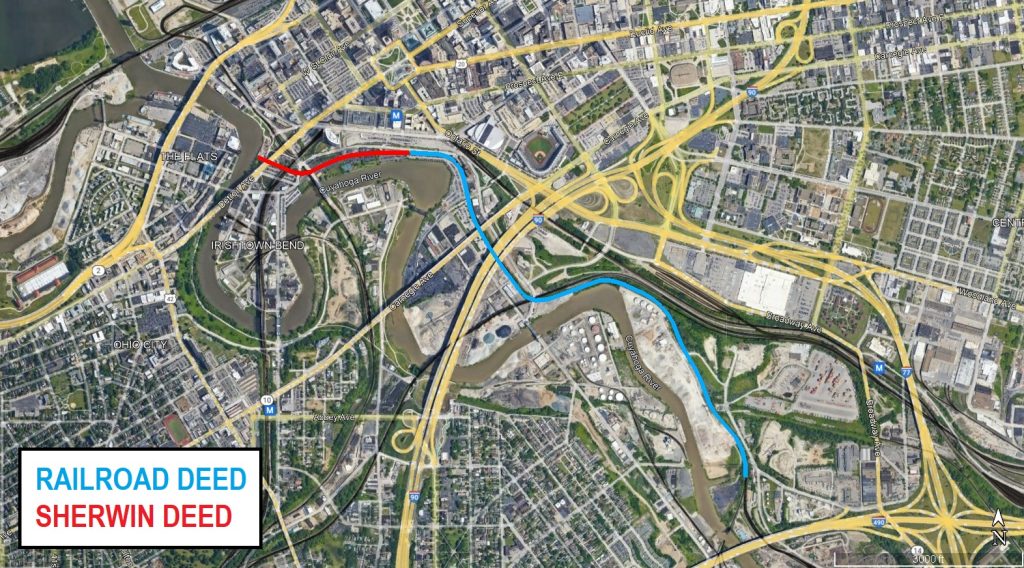

On June 8, exactly one week before she was fired, the city’s Director of Economic Development Tessa Jackson signed a release of lien on two sections of former Baltimore & Ohio Railroad (B&O) which is now a part of CSX Transportation Inc., a large freight railroad company. One section of right of way is called the “Sherwin Deed” and includes no more than a few thousand feet of former railroad track past Sherwin-Williams’ Breen Research Center, 601 Canal Rd. That property transferred to Bedrock today but has been in the works since early 2022. The other section of rail right of way is called the “Railroad Deed” and includes a roughly 1.5-mile-long intact rail corridor with unused tracks on it, south to I-490.

“As part of the Cuyahoga Riverfront Master Plan, Bedrock has officially closed on its acquisition of the Sherwin-Williams properties,” Bedrock Cleveland said in a written statement today. “This includes the Landmark Office Towers and Breen Technology Center. Also, purchased was the former vacant Baltimore & Ohio Railroad Building.”

Having active liens on properties complicates if not prohibits sales of property, which is why the city released itself from the “Sherwin Deed.” That deed is from 1985 and allowed Sherwin-Williams to expand the site of its Breen Research Center onto former B&O land. The “Railroad Deed” dates to 1980 when the city sold its ownership of the former Ohio & Erie Canal right of way on which predecessors of the B&O in the 1880s built tracks into downtown from Akron. The city sold its interest for $1.5 million in the former canal bed-turned-railway after the city defaulted on its finances in 1978 and sought to raise money and cut costs to pay off creditors, according to public records.

Both deeds, enacted by City Council ordinances and adopted by the city’s Board of Control, contained reversion clauses. The reversion clauses not only gave the city a right to access those current and former railroad rights of way, they also gave the city the right to take back those rights of way without compensation to their current owners, according to the deed transfer documents that are publicly available from the Cuyahoga County Fiscal Office.

“This conveyance (of ownership) is made,” said the 1980 Railroad Deed, “notwithstanding the fact that valuable consideration has been paid, upon the express condition that if the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad Company shall fail to use, maintain and operate the premises as described herein for railroad purposes, then the right, title and estate of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad Company to the property herein conveyed by the City of Cleveland shall determine and become void, and shall revert to the and become absolutely vest in the City of Cleveland or its successors and assign together with all improvements thereon. In the event of reversion of the premises the cash consideration shall not be repaid by the City of Cleveland to the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad Company.”

A source familiar with the situation said Jackson and Richard Bertovich, the city’s chief assistant director of law who apparently drafted the lien release, should at least have sought approval from City Council before executing the release. And the source said the city should have also requested compensation from Sherwin-Williams and CSX Transportation before walking away from its rights to a valuable piece of property. No compensation was apparently paid by either party.

“The lien release was part of a development agreement the city entered into prior to my joining the administration,” Jackson said on Twitter. “A public records request for the related ‘attorney assignment’ would’ve confirmed that initiating this lien release was above my pay grade. Hint: While the mayor’s chiefs may have the power to make promises, they don’t have legislative authority to sign off on them.”

An e-mail sent by NEOtrans to the city’s Press Secretary Marie Zickefoose seeking comment was opened but not responded to prior to publication of this article. A phone message left for Ward 3 Councilman Kerry McCormack, chair of council’s Transportation and Mobility Committee, was not returned.

“The Railroad Deed and the Sherwin Deed (collectively, the “Deeds”) contain certain rights, covenant, conditions, easements and restrictions in favor of the city, including, without limitation, rights of re-entry and reverter, also referred to as a reversionary interest (collectively, the “Deed Restrictions”). And the city desires to terminate, extinguish and forever release all of the deed restrictions by terms of this release,” the lien release reads.

“It appears that the city of Cleveland may have significantly harmed the prospects for extending Cuyahoga Valley Scenic Railroad trains into downtown Cleveland,” said Stu Nicholson, executive director of All Aboard Ohio, a nonprofit passenger rail and public transit advocacy association based in Columbus. “I understand releasing its lien on the former railroad land next to Sherwin-Williams. But why was it necessary to release its lien to the intact rail corridor south of there to near I-490? That lien would have put the city in a dominant position to negotiate for the extension of scenic railroad trains. Now it puts CSX, a notoriously anti-passenger railroad, at the controls.”

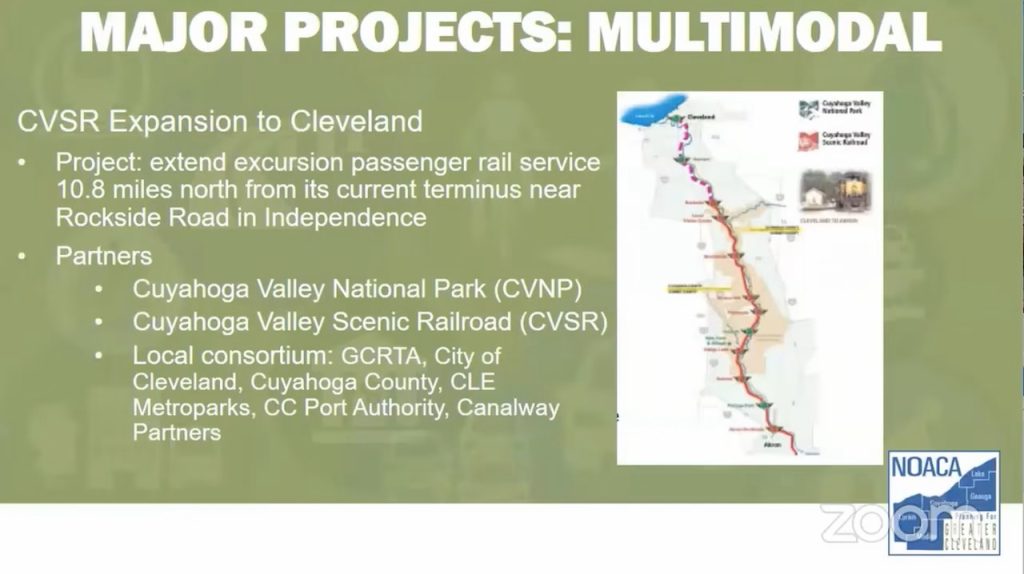

Slide from a presentation at a Northeast Ohio Areawide Coordinating Agency meeting last January about the proposed Cuyahoga Valley Scenic Railroad extension (NOACA).

NEOtrans also contacted CSX Transportation’s media relations staff, without response yet, to inquire about the company’s intentions for its tracks along the Cuyahoga River, especially the northern portion of what CSX officially calls its Cleveland, Terminal and Valley Subdivision. The tracks cross the river on a movable bridge below I-490 which is still used by CSX to access the Cleveland Cliffs steel mills and other shippers. Farther south, the track continues through Clark Yard, past Steelyard Commons and to a railroad location near Granger Road in Independence called Willow where freight trains go no further, according to railroad employee timetables available on the Web. South of Willow to Akron, the tracks are owned by the National Park Service which pays CVSR to provide rail service.

Greater Cleveland’s metropolitan planning organization, the Northeast Ohio Areawide Coordinating Agency (NOACA), is moving forward on conducting an $800,000 feasibility study of extending CVSR trains from their northern terminus at Rockside Road in suburban Independence to downtown Cleveland. NOACA Executive Grace Gallucci did not respond to a NEOtrans e-mail regarding the status of the feasibility study including which consultants were hired to conduct it.

Two decades ago, CVSR-led studies showed that an extension 10 miles north to downtown Cleveland could cost about $20 million in track and other infrastructure improvements. The result would be an increase of annual ridership from about 200,000 passengers pre-pandemic to 300,000 passengers after the extension. It would also provide Cleveland school children with educational trips to the Cuyahoga Valley National Park as well as access from southern suburbs and Akron to downtown Cleveland plus up to two additional en route stations such as for the Cleveland Metroparks Zoo, Steelyard Commons and expansion of CVSR’s Bike Aboard program to the entirety of the Towpath Trail, backers said. Since that effort two decades ago, CSX has blocked all attempts at extending CVSR to downtown Cleveland, Nicholson said.

A city of Akron official told NEOtrans that extending CVSR service to downtown Cleveland is one of the goals listed in the Cuyahoga Valley National Park’s (CVNP) recent draft Community Access Plan. The plan said the extension supports the park’s goal of encouraging alternative options to accessing the park, rather than by car. Many Cleveland-area residents are without access to a vehicle, so the extension encourages equitable access to the park. Reducing car visitation would help address the park’s road and parking congestion issues while reducing air pollution in the Cuyahoga Valley and cut climate change-causing emissions. And it enables park visits by out-of-state visitors from Hopkins International Airport via the rapid transit line to CVSR, which allows park visits without a vehicle.

“That experience is not possible in a lot of other National Parks,” the CVNP’s draft Community Access Plan reads.

END