One of Cleveland’s high-frequency transit corridors is Detroit Avenue on the city’s West Side. But despite short sections of dense, mixed-use districts like this along the No. 26 bus route, most of the corridor has lost its transit-supportive land use built in the streetcar era. Restoring that walkable density cannot be done without breaking city zoning laws or going through a costly and complex variance application. A proposed city law seeks to change that (Google). CLICK IMAGES TO ENLARGE THEM.

Ordinance could boost investment in transit corridors

The city of Cleveland’s Board of Zoning Appeals’ docket regularly sees cases like this. On Monday, Sally Banks LLC will ask the board to allow it add a 1,100-square-foot addition to its popular Treehouse pub, 820 College Ave. in Tremont, without adding off-street parking spaces. It’s the second time the pub is expanding and it’s the second time it has had to go through the process of getting a variance to ignore the city’s zoning laws. Those zoning laws say the pub has to add an off-street parking space for every 100 square feet of new business space. The average cost per parking space to build a surface parking lot is $5,000, city data shows.

That’s an unnecessary expense for a pub that gets a lot of walk-in business from the densely populated and growing urban neighborhood that, like the snake eating its tail, would have to increasingly demolish itself to add more parking. Worse, the zoning code fails to acknowledge the availability of existing transportation. The pub is located on a bus route with 24-hour service. And simply having to go through the process of getting a variance can be convoluted and expensive, too. Not every property owner or developer is willing to go through with it, reducing job opportunities and risking more land ending up in property purgatory — the city’s land bank of vacant lots.

“To be successful, our bike and transit networks must safely, conveniently and reliably connect people to the places they want to go,” said Matt Moss, manager of Strategic Initiatives for the City Planning Commission. “While over 200,000 jobs and nearly half of the city’s total population are located within a 5-minute walk of a high-frequency transit stop, there are also 17,000 vacant lots totaling over 2,800 acres in this footprint. This is a huge opportunity to make our neighborhoods more enjoyable places to live and work, and the city must align its rules and regulations to support investment into these areas.”

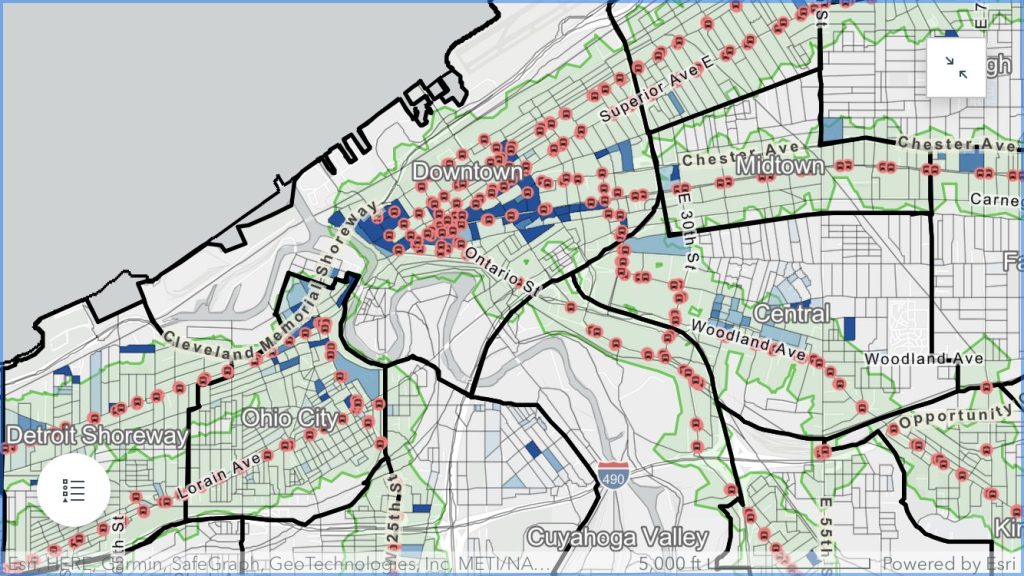

At a presentation yesterday before the commission’s Design-Review Committee, Moss laid out the details of a proposed new ordinance that was submitted to City Council. That ordinance, if adopted, would create a Transportation Demand Management (TDM) program to allow Transit-Oriented Development (TOD) within a five-minute walk of all high-frequency transit stops (on bus routes or rail stations with daytime service every 15 minutes or better). Those areas, called by the commission as “The TOD Zone,” have 78 percent of the city’s jobs but only 23 percent of its housing. And 70 percent of those households have zero cars or just one car that is often shared. That creates a physical disconnect between jobs and job-seekers, worsening poverty and crime.

The change should also create more affordable housing products because of the high cost building parking lots and especially parking decks that cost an average of $25,000 per space for an above-ground garage or $35,000 for below-ground garages. On average in Cleveland, at least 17 percent of a housing unit’s rent is attributed to parking, city data shows.

Every new building in Little Italy looking west along Mayfield Road toward the Red Line rail station had to get permission from the city to avoid breaking the law. Even though the buildings were built next to a high-frequency transit route and cater to residents who walk or ride to work or school, their developers had to pay more to either add enough parking to be legal or to apply for variances from the city (Google).

The new program will also “legalize” many of Cleveland’s treasured commercial and cultural districts, Moss said. Many popular mixed-use areas like Little Italy, Ohio City, Waterloo in Collinwood, Gordon Square, Old Brooklyn, or Tremont could not be built today under the current zoning code and do not meet currently mandated parking requirements. In order to develop these and other areas, any applicant must go through a difficult process to get a variance or pay for expensive parking. Prospective residents, businesses and developers too often decline to invest, leaving a given building or property vacant.

Moss noted that the Federal Transit Administration considers a transit-supportive housing development as one with 25 to 35 housing units per acre. If the 2,800 acres of vacant land in The TOD Zone gained an average of 30 housing units per acre, it would result in 84,000 new dwellings. With an average household size in Cleveland of 2.4 persons per home, that’s 201,600 people added to within a five-minute walk of a high-frequency transit route. While those numbers are not stated goals of the city, the result of it is — to address conditions what Mayor Justin Bibb considers to be a public emergency: “intersecting public health, climate, municipal finance and human thriving,” Moss said in his presentation, describing the creation of walkable, mixed-use density in transit corridors as creating a “15-minute city” for everyone, not just motorists.

“It’s really important to Mayor Bibb in terms of how we look at land-use development patterns across the city now and in the future,” Moss explained. “Essentially what it is is a vision for Cleveland where you can access your basic needs and accessing amenities particularly by walking, bike ride, transit trip or car rides. We really mean the use of all modes. However, Cleveland is already a 15-minute city if you’re driving. You can get just about anywhere you need to go in 15 minutes by car. So that box is checked. What we’re focusing on is the other modes, elevating walking, biking and public transit to that same level of accessibility.”

TOD is a land use pattern that centers mixed-use, walkable developments around transit infrastructure. It prioritizes mobility for people and reduces dependency on cars as the only reliable or convenient mode of transportation. TOD in Cleveland has been a focus for new investment, but permitting TOD along our existing transit corridors makes it easier to maintain and renovate existing buildings.

“In Cleveland, we see a lot of TOD in the form of new investment,” Moss said. “But we also see TOD as an adaptive reuse strategy too. Cleveland originally was a transit city. We were built along the streetcar network. We have the legacy of those historic buildings today in many of our neighborhoods.”

As pilot project for the city’s proposed Transportation Demand Management policy, Stokes West was allowed to provide 35 percent fewer parking spaces than the city’s current law allows by providing other features to the 261-apartment development to encourage residents to use travel modes other than the car. They include discounted transit passes, shared bike and scooters, and more pedestrian-friendly landscape features (LDA).

City officials say the problem is that zoning on about 60 percent of the land within a five-minute walk of high-frequency transit does not permit more than two units of housing to be built. The administration proposes to add flexibility to the zoning code to allow several types of more dense housing construction. Those include “accessory dwelling units” (ADU — a legal and regulatory term for a secondary house or apartment that shares the building lot of a larger, primary home), the “Missing Middle” of housing that’s between low-income and luxury, as well as the addition of more large-scale multi-family buildings.

“We’re excited to take the next step, moving this into policy,” said City Planning Director Joyce Pan Huang. “A piece of legislation was introduced last week, July 12, at City Council. While it is not before you (planning commission) as a vote today, this (presentation by Moss) is information only. They will be before next meeting as a mandatory referral. So we wanted to give you time to understand the policy, to digest it, and then bring it before you next time.”

Six months after City Council passage, the ordinance would go into effect. It would create a TDM points-based scoring program for proposed development projects up for review by the planning commission. Each could be evaluated by how they meet the TDM strategy. As proposed, a large project like the 261-apartment Stokes West project in University Circle scored enough TDM points — in this case 32 TMD points to meet TDM program requirements on a trial basis last May. Developer Brent Zimmerman consented to have his project be a guinea pig for the TDM strategy because it allowed him to reduce the number of parking spaces to 89, or 35 percent below what would otherwise be required for the site..

As a result, Zimmerman said the waiving of the parking minimum significantly reduced his development costs. The Stokes West project scored more than enough TDM points by subsidizing transit passes at 40 percent for tenants, adding a streetscape that prioritizes pedestrians, bicyclists and transit riders, providing secure long-term bicycle parking on site, having a bike repair station and bike-share fleet for tenants, unbunding parking spaces from each tenants’ rent and providing a shared on-site mobility hub offering the use of scooters and bikes.

Other strategies on the TDM scorecard include a parking supply reduction, having a transit information kiosk (like the West 73rd Street Apartments), car-share membership, providing vanpool or shuttle bus services, on-site child care, family amenities and storage, and a delivery area. All of those have different scores to contribute to a project that, when enough are totaled up, could be amount to a score high enough to allow the project to reduce its parking to whatever level the owner and its surrounding community needs to achieve their goals.

Waiting areas in the vestibules of the proposed West 73rd Street Apartments are among the transportation demand strategies that allow the project to have a parking-to-apartment ratio below 1:1. The vestibules not only will offer a place to wait for rideshare like Uber or Lyft. They also will have transit service information display boards, seen at right (Horton Harper).

Transportation Demand Management (TDM) focuses on understanding how people make transportation decisions and influencing people’s behavior to use existing transportation infrastructure in more efficient ways. TDM guides the design of transportation and infrastructure so that options other than driving are naturally encouraged and transportation systems are better balanced. Simply put, it is a set of strategies aimed at maximizing traveler choice to create more freedom in how to travel around the city. Smaller projects would be exempt from the TDM strategy which is different from other cities’ strategies Moss researched because Cleveland already has many small-scale buildings that have no off-street parking.

“Essentially, in many of the small retail storefronts that characterize a lot of our historic neighborhoods, occupying those spaces doesn’t have a huge impact on our transportation system,” Moss said. “Often times there are stores that are less than 5,000 square feet and have a handful of (dwelling) units above that storefront, but they’re still required to have the same footprint of that building if not larger required for off-street parking. So by allowing those projects to go through without an onerous variance process, we actually make it easier to use the transportation system by walking, biking or transit by reactivating that space.”

Larger projects applying for planning commission approval would need to show justification for seeking TDM measures and a reduction in parking. Justification could include developing a site near a transit stop or a multi-purpose trail. A plan for implementing/maintaining TDM features as well as a monitoring and reporting plan would need to be submitted to the city. That last part raised some clarification questions from commission members including from Chair Lillian Kuri on whether developments would be required to have less parking.

“We’re not requiring developers to build less parking,” Moss said. “They can still propose the parking that they need or that they might want in order to program and lease their project. But right now it’s not an option. They have to do this (provide more off-street parking) per code. Mandatory parking requirements are exclusionary and make housing artificially more expensive.”

Commission member Denise McCray-Scott said she wanted to hear more about how public safety figures into the conversations for supporting the development of neighborhoods in the 15-minute city vision.

The lack of transit-supportive housing densities (shown in blue) within a five-minute walk (green shade) of stops (red icons) on high-frequency bus and train routes creates a physical disconnect between jobs and job-seekers, causing higher poverty and crime, city planners said. Removing legal barriers to building transit-supportive development is the goal of a proposed new city program (CPC).

“I’m all for increasing our bike, transit and other multi-modal modes of transportation, but factoring in the data about what’s happening in the city of Cleveland as it relates to safety, I think it’s important to have input of stakeholders who are working in that space,” McCray-Scott said.

Commission members also wanted to know about how the city would manage the new program. Moss said if a project’s design and its TDM strategy is approved by planning commission, the project would achieve TDM registration with the city’s Division of Licenses and Assessments. It will require an annual renewal for the first three years followed by a requirement of every three years assuming consistent compliance. Applicants can modify and adapt their TDM program over time. Fees will be set by the city’s Board of Control as will fines for non-compliance.

“It’s not any different than assessing parking lots,” said commission Vice Chair August Fluker.

Moss said if a property owner doesn’t comply with the TDM strategy they requested and got approval for, the city’s Division of Licenses and Assessments could warn the owner and fine them if they don’t respond. If the fines reach a certain level without response, then the city could take the property owner to court.

“The conversations we’ve been having with developers, it’s really expensive to build parking,” Moss noted. “It makes it difficult for them to provide other amenities. Again, I’m speaking specifically about larger developments where they want to provide amenities that, either the neighbors are asking them to, or they want to include to attract residents in a competitive housing environment, they simply can’t do that.”

END