A part of the city of Cleveland’s lakefront plan that doesn’t get the attention is just east of downtown where the Shoreway highway would become a boulevard and East 18th Street is extended from behind the smokestacks at left, down the bluff on an S-curve toward the foreground to an intersection with the boulevard. Also a middle portion of the Municipal Parking Lot near a Waterfront Line light-rail station could be developed with workforce housing (Google). CLICK IMAGES TO ENLARGE THEM.

City Council could vote Sept. 9 to implement plan

One of the most important pieces of legislation regarding the future of Downtown Cleveland’s lakefront is working its way through Cleveland City Council. The proposed ordinance amendment, if passed at council’s next regular meeting Sept. 9, would codify the desired lakefront land-use features and set the city on a course to implement them. In other words, it would no longer be a lakefront plan, but a lakefront project.

When approved, the Mayor’s Office of Capital Projects (MOCAP) would be authorized to direct final engineering and design work for the lakefront plans and components by Osborn Engineering of Cleveland. If already requested funding is secured, construction contractors could be hired in 2026 with construction work getting underway in 2027 and taking about three years to complete, according to a summary of the legislation.

In a transportation and land-use planning process that is seeking federal construction dollars, the plan-sponsoring entity must develop options to consider, get public input on them, and make a decision of what, if anything, to build. That decision of what to build is called the locally preferred alternative. The city of Cleveland is the plan-sponsoring entity in this case.

Since municipalities are empowered by the Ohio Constitution to determine their land use, having the city of Cleveland decide the locally preferred alternative here gives the chosen components of the lakefront land use plan the force of law. Those components are in the ordinance amendment language that was added by City Council on Aug. 7 — two days after a public engagement session on the final lakefront plan.

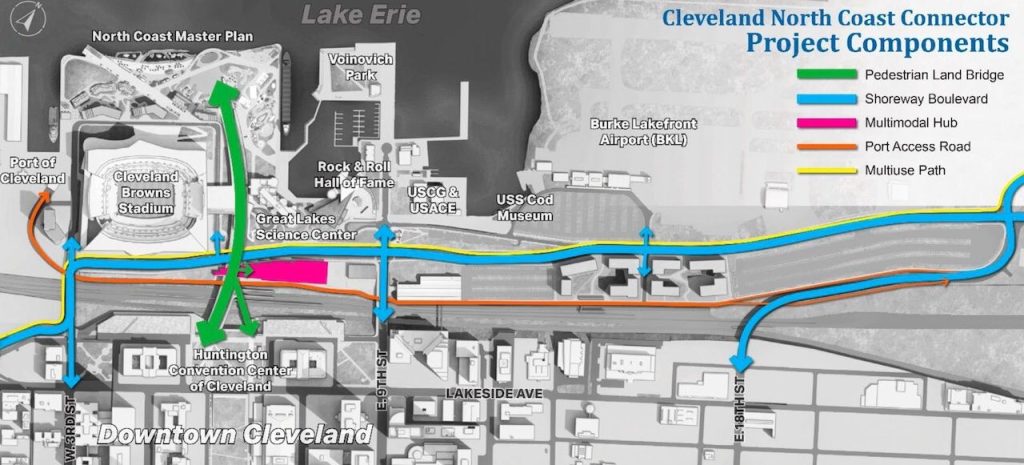

This map shows the major features that are included in Cleveland City Council’s ordinance amendment, plus an authorization for final design work to begin to implement lakefront improvements as a project rather than just a plan. However the multimodal hub is farther behind in its development and thus not part of the amendment (MOCAP).

Although the lakefront effort is titled the “North Coast Connector Project” (also known as the Lakefront Pedestrian Bridge Connector), it is much more than that. The plan’s locally preferred alternative would have these features:

- Construction of a 120-foot-wide non-vehicular bridge connecting Mall C to the lakefront;

- Partial reassignment of State Route 2 between West 3rd Street and Interstate 90 from limited-access to local-access roadway;

- Reconfiguration of nearly 2 miles of State Route 2 and Port Road relocation;

- Addition of an intersection and roadway for the East 18th Street extension;

- Removal, installation and/or construction of all other improvements including drainage upgrades and utility relocations;

- Installation of curbs, sidewalks, driveways, pedestrian, bicycle and multi-modal paths/trails, traffic and pedestrian signaling, signage, markings and all other appurtenances necessary for completion of the project.

The straw that’s stirring the drink in Downtown Cleveland lakefront planning is the proposed North Coast Connector or Lakefront Pedestrian Bridge Connector. Everything else is stemming from that including the conversion of the Shoreway into a boulevard, a multimodal transit hub and waterfront public spaces and amenities. Whether the Cleveland Browns Stadium is among them remains to be seen (FO).

The city is seeking $260 million from the U.S. Department of Transportation’s (USDOT) National Infrastructure Project Assistance program, dubbed the Mega Program, to build these features. The Mega Program funds no more than 60 percent of a project’s cost. A preliminary cost of the lakefront plan elements is $440 million. If it’s more than that, it would have to come from other sources.

One of those sources already identified for matching the federal dollars is the city’s Shore-To-Core-To-Shore tax increment financing (TIF) district that’s expected to generate at least $2.9 billion for public works projects over 30 years in and near downtown. That amount does not include the new Downtown Riverfront TIF council passed earlier this month.

City Council would need to vote on the ordinance amendment soon, as the Mega Program grant awards could be decided by the end of September. Federal agencies award funds only to projects that have a locally preferred alternative identified, according to planners who addressed the public at recent lakefront meetings.

Of course, the biggest question left unanswered is what will happen with Cleveland Browns Stadium and the 31 acres of city-owned lakefront land on which it sets. The open-air stadium could get reconstructed for $1.2 billion or it could be demolished in favor of a new $2.4 billion domed stadium in suburban Brook Park.

In the event the latter happens, the city’s lakefront masterplan consultant James Corner Field Operations of New York is developing alternative concepts for reusing the stadium land. While the use of the 31 acres on which the stadium sets could change, city officials said the lakefront project elements identified in the ordinance amendment would not change whether Cleveland Browns Stadium remains on the lakefront or not.

Between downtown’s Warehouse District and Lake Erie, the Shoreway above is to be brought down to street level and Summit Street is to be erased for a boulevard that ramps down from the Main Avenue Bridge across the Cuyahoga Valley. That boulevard will intersect and briefly share a widened bridge with West 3rd Street in the background, over the lakefront railroad tracks, before continuing east as a boulevard to Interstate 90 (Google).

Not yet included is a multimodal transit center that could combine the Greater Cleveland Regional Transit Authority’s light-rail Waterfront Line’s West 3rd and East 9th Street rail stations into a facility shared with a new Amtrak passenger railroad station, regional and/or intercity bus station and structured parking. That project, which is further behind the pedestrian bridge work, is being pursued separately as is an $8 million planning grant from the Federal Railroad Administration.

Ohio Department of Transportation Director Jack Marchbanks, in a May 6 letter to USDOT Secretary Pete Buttigieg endorsing the city’s Mega Program application, said the pedestrian bridge, the Shoreway’s conversion and related improvements all needed to come first. Marchbanks is leaving ODOT Sept. 30.

“This project will support a myriad of local and regional benefits, including … the foundation for an expanded multimodal transportation facility that integrates interstate

and regional rail and bus service,” Marchbanks wrote.

Marchbanks said he supported the conversion of the Shoreway into a boulevard because the 1930s-built highway does not meet contemporary design standards for safety. Of particular concern to ODOT is the proximity of on-off ramps between West 3rd and East 9th.

Where there are currently three intersections along this short stretch of East 9th Street near the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame could soon be just one — for the Shoreway reconfigured as a boulevard. Looking south here, there are intersections for Erieside Avenue, the westbound Shoreway ramps and then then eastbound Shoreway ramps. The new boulevard will intersect with East 9th where the westbound ramps are now (Google).

Closing ramps to either of the streets greatly restricts access to/from downtown and there is no room on the lakefront to build looping or braided ramps while deferring to the city’s vision for a pedestrian- and bike-friendly lakefront. At the same time, ODOT traffic studies showed that turning the highway into a boulevard with intersections at West 3rd and East 9th would create too much traffic congestion if not for the planned extension of East 18th Street to the boulevard.

“It (the overall project) will mitigate or eliminate the barriers to the lake and improve regional transportation infrastructure through the construction of a 120-foot-wide land bridge, removal of substandard ramps, and the major reconfiguration of a nearly 2-mile segment of freeway into a modern, safe and efficient multimodal boulevard,” Marchbanks said.

Passenger rail advocates said the extension of East 18th to the Route 2 boulevard, proposed as a snaking roadway coming down from a bluff overlooking Lake Erie, could pinch rail service expansion plans. Those plans may depend on a potential train storage and servicing yard just east of the proposed multimodal station. Called the East 26th Street rail yard, the unused land has its ownership split between passenger railroad Amtrak and freight railroad CSX.

“We applaud the city for moving ahead with its vision for the lakefront,” said Lakeshore Rail Alliance spokesman Bill Hutchison. “The proposal to extend East 18th Street should take care to not encroach on the East 26th Street rail yard. This facility will be needed as a layover for trains which will serve the 3C&D and Cleveland-Toledo-Detroit corridors.”

END