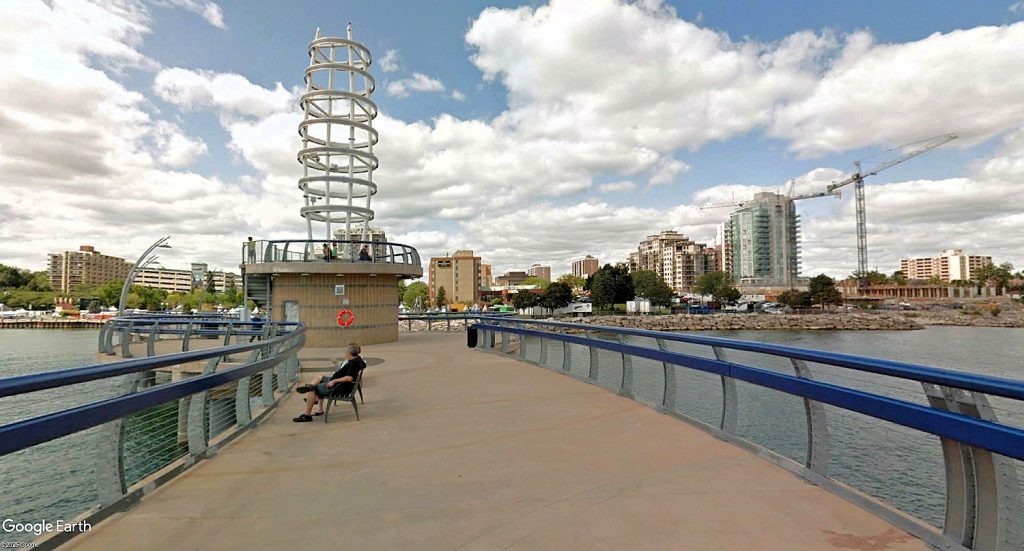

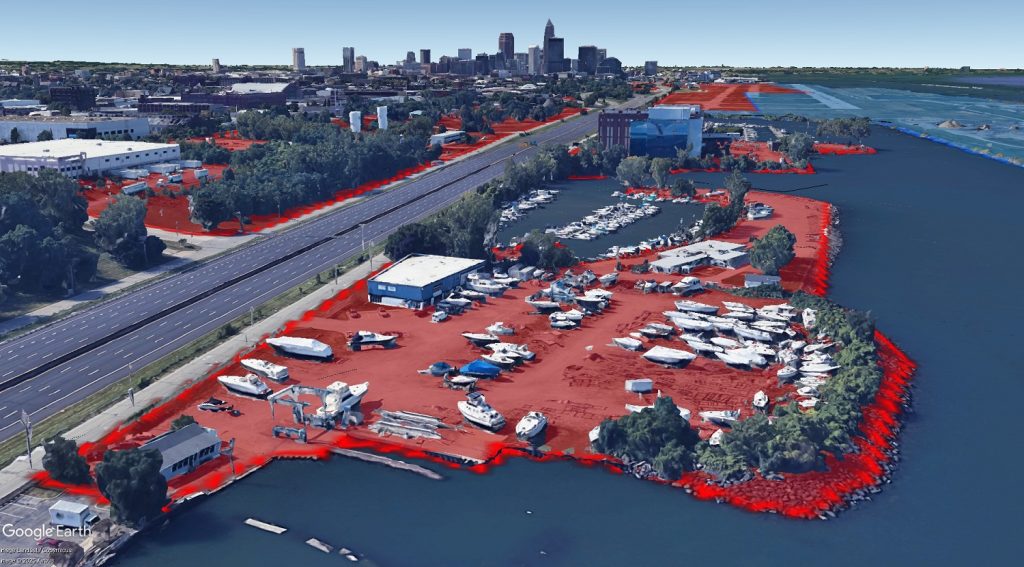

The red lands are properties owned by the city of Cleveland along its Lake Erie waterfront just east of downtown. The light-blue land at right is another publicly owned piece of land owned by the state of Ohio. In the foreground is the Forest City Yacht Club that’s been on city-owned land for nearly a century. Beyond is the 115-year-old Cleveland Public Power’s Lake Road Power Station. Few of these publicly owned properties are publicly accessible nor do they represent the highest and best uses of lakefront land (Google). CLICK IMAGES TO ENLARGE THEM.

1,000 acres of land near lakefront publicly owned

A COMMENTARY

One year ago, the City Planning Commission “hired” Cleveland State University’s 17th Street Studios for a Masters of Urban Planning and Development (MUPD) capstone project to look at how to enhance the underutilized light-rail Waterfront Line. One of the findings was that the city of Cleveland literally owned its own ability to boost the rail line and the lakefront overall.

A barrier to boosting the line was that profitable, private parking lots abound along the Waterfront Line. The students’ 17th Street Studios suggested city incentives such as grants, tax credits and supportive zoning could encourage property owners to part ways with their parking lots so they could be developed with ridership-generating land uses.

But the students discovered that one of the biggest owners of parking lots and other land along the rail line was the city itself. So the students’ consulting team suggested the city consolidate parking lots into garages at strategic locations and offer the freed-up land for transit-oriented development (TOD).

Unfortunately, little or no public action has come of the students’ thoughtful suggestions since then. However, another student-driven urban planning exercise involving the Cleveland lakefront, potentially benefitting the Waterfront Line, did occur earlier this year.

Section 1 nearest to Downtown Cleveland including Burke Lakefront Airport and the Municipal Parking Lots. The city of Cleveland owns the properties near the lakefront as shaded in red. Other public-sector entities own the properties shaded in blue. The light-rail Waterfront Line is shown in bright green and its extension eastward along the CSX railroad right of way is shown in faded green (Google, MyPlace.CuyahogaCounty.gov, NEOtrans).

Last month, a team of Harvard University and Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) students won the top prize in a global competition for its redevelopment plan for the 62-acre site of a former coal-fired power plant at 6800 S. Marginal Rd. The contest was the 23rd annual Urban Land Institute(ULI)/Gerald D. Hines Student Urban Design Competition.

Their “Lakeshore” plan proposed a multi-phase, 2.25-million-square-foot mixed-use development with a project value of more than $1.1 billion. Not only would it tap into the Port of Cleveland’s/Cleveland Metroparks’ CHEERS lakefront project to expand the lakefront land area, but it would be served by a rail transit station.

While admittedly an academic exercise without investors’ dollars behind it, all of the 83 global competitors in the ULI Hines content came up with similar mixed-use megaproject dream scenarios for the site. And it was done with the blessing of the property owner, an affiliate of Utah-based Industrial Development Advantage, LLC. It remains to be seen what it does with this huge site.

But as big as that vacant piece of land is, it is small compared to the amount of publicly owned land along the lakefront. And it’s all within a few minutes walk of either side of an underutilized railroad corridor along the waterfront from downtown to Collinwood. We’ll get back to that railroad corridor later.

Section 2 amid the East 55th Marina, ex-Lake Shore Power Station site and Gordon Park. The city of Cleveland owns the properties near the lakefront as shaded in red. Other public-sector entities own the properties shaded in blue. The light-rail Waterfront Line is shown in bright green and its extension eastward along the CSX railroad right of way is shown in faded green (Google, MyPlace.CuyahogaCounty.gov, NEOtrans).

NEOtrans has identified more than 1,000 acres of publicly owned lakefront land from east of East 9th Street in downtown Cleveland to Collinwood. And that doesn’t include the eight-lane-wide State Route 2/Interstate 90. But it does include other publicly owned lands that may or may not be developable. And, of course, we want more publicly owned land along the water’s edge.

That’s not the problem here. Instead, the problems are two-fold. Even though there’s lots of publicly owned land along the lakefront east of Downtown Cleveland, it’s not publicly accessible. You can’t walk, bike, picnic, swim, fish, throw a football or Frisbee or do any other park activities along roughly seven of those 12 shoreline miles from East 9th to the Easterly Wastewater Treatment Plant.

The biggest chunk of publicly owned land in this area is Burke Lakefront Airport — comprising 450 acres. A study by the city shows Burke could be repurposed into a mix of recreational greenspace and waterfront development but not easily. Point is, it’s not publicly accessible now.

The other problem is that many more publicly owned pieces of land are not publicly accessible. There’s the U.S. Coast Guard Station, Cleveland Mounted Police, Joseph Stamps Service Center, Kirtland Pump Station, Cleveland Public Power Plant, Forest City Yacht Club, Ohio Department of Transportation maintenance facility, and various city land bank lots.

Section 3 along Interstate 90, Bratenahl and current/future Job Ready Sites. The city of Cleveland owns the properties near the lakefront as shaded in red. Other public-sector entities own the properties shaded in blue. The light-rail Waterfront Line is shown in bright green and its extension eastward along the CSX railroad right of way is shown in faded green (Google, MyPlace.CuyahogaCounty.gov, NEOtrans).

Plus there’s the old Cold War anti-aircraft missile site that’s still owned by the U.S. government land at 8907 Lake Shore Blvd. in Bratenahl, the vacant Charles Lake school site, city-owned lands along East 110th Street, Cleveland’s Kirby Avenue Water Pollution Control Center, two huge Job Ready Sites parcels just east of it, and a Northeast Ohio Regional Sewer District property on the other side of the tracks.

Some of those uses still need to be there, doing what they’re doing now. But not all of them. And some of them are ripe for redevelopment into uses that could better capitalize on lakefront access and views.

Even the existing public parks on the waterfront, like the Cleveland Metroparks East 55th Street Marina and Cleveland’s Gordon Park, can be and are being redeveloped with new uses so the public can enjoy them more. One of those, the Parker Sailing Center at East 55th, just had its groundbreaking last week.

But there’s roughly 140 acres of publicly owned land near the lakefront that is not being put to its highest and best use, where people can live, work, shop and play along a Great Lake and contribute to the city’s tax base. Add to that the former Lake Shore Power Station that was the subject of the global competition and it totals about 200 acres of developable land (even without Burke).

Developed with transit-supportive housing at an average of 30 units per acre, an average household size of 2.4 persons and an average retail square footage of 23.5 square feet per person, the Lakeshore East becomes populous enough to be its own transit neighborhood. For the math-challenged, that 200 acres could accommodate 6,000 housing units, 14,400 people and 338,400 square feet of neighborhood retail.

There’s no reason why the Lakeshore East stretch of the city’s lakefront shouldn’t be enjoying the same kind of post-industrial rebirth like what has been happening in an area one-third its size so far this century near Edgewater Park.

The addition of more than a thousand housing units in Gordon Square, including Cleveland lakefront’s first high-rise apartment building outside of downtown, on polluted former industrial sites, has rejuvenated those lands and, by extension, the Detroit Avenue commercial corridor to the south.

Perhaps a Lakeshore East rebirth could do the same for the St. Clair Avenue commercial corridor. The St. Clair-Superior area is already seeing the growth of an arts district, including galleries, arts suppliers, sculptors and arts-related metalworking.

It’s not just Chicago or Toronto that Cleveland can learn from in providing more livable settings along its Great Lake waterfront. Milwaukee, despite having Lincoln Memorial Drive separate its Lower East Side and Yankee Hill neighborhoods that are north of downtown from its parks and marinas along the water’s edge, is a model for Cleveland’s lakefront (Google).

The city is thinking in these terms now with its latest lakefront plan that includes redeveloping some of the Municipal Parking Lots along the Waterfront Line with transit-supportive affordable housing. It’s a good start.

A public-private partnership could catalyze redevelopment of a Lakeshore East district, including the use of tax-increment financing to support the addition of crucial infrastructure here. One piece of infrastructure that could catalyze this district’s rebirth is the extension of the underutilized Waterfront Line.

The key is the CSX-owned railroad corridor between downtown and Collinwood. It once had four main tracks to handle lots of freight and passenger traffic plus various industrial sidings to reach online shippers but now has only one main track and an occasional siding track.

Since 1999, the biggest user of that railroad corridor is Amtrak for its nightly passenger service; CSX freight trains now travel across the eastern and southern part of the city. For roughly 6 miles, the railroad right of way is plenty wide to accommodate the construction of two light-rail tracks within it.

At right is Lake Erie and the Forest City Yacht Club which leases city-owned land behind that barbed-wire fence. Next to it is North Marginal Road which lacks sidewalks or a bike path, for now. To the left is Interstate 90 and beyond that is a mix of fenced-off public service facilities and private industries with the CSX railroad atop the lakefront bluff. Little of it publicly capitalizes on the presence of a Great Lake here (Google).

But 4.5 miles of railroad right of way might not need to. That’s because it adjoins a beaded necklace of publicly owned lands on the north side of the railroad, which is the side of the railroad on which the Waterfront Line runs west of its terminus near the South Harbor station.

To save money, the Waterfront Line could be extended east over some of that land and strips of railroad right of way could be vacated to the neighboring public owners. Cleveland’s lakefront plan in the early 2000s proposed this light-rail extension to at least Bratenahl.

There’s no reason the lakefront east of downtown shouldn’t be lined with a mix of low-, medium- and high-rise developments built atop neighborhood retail and restaurants amid public spaces and connected to the water by pedestrian overpasses or even freeway cap parks over Interstate 90. And all of it could be supported by an extension of the Waterfront Line.

Great Lakes cities like Milwaukee, Chicago, Toronto that love and capitalize on their waterfronts offer similar amenities, settings and services when there’s a will that creates the way. It’s an opportunity that Cleveland already owns. It’s only the lack of will that has gotten in our way.

END