With Lake Erie and Interstate 90 in the foreground, the background is changed from a polluted former power plant site into a dynamic urban community between Gordon Park and East 55th Street. This concept, by a partnership of Harvard University and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, was just one of 82 submitted to an international design competition (Harvard-ULI). CLICK IMAGES TO ENLARGE THEM.

Urban Land Institute contest draws big ideas

With deference to the classic movie “Casablanca,” of all the abandoned industrial sites in North America, the Urban Land Institute’s (ULI) Hines Student Competition picked Cleveland’s vacated Lake Shore Power Plant site as the canvas for its 2025 design competition. Four finalists were announced today in the competition that drew 82 entries from universities worldwide, with the winner to be named April 3 in Cleveland.

Not only is the selection of competition finalists a big deal for the entrants, it’s a big deal for the Lake Shore Power Station to be the subject of such a prestigious competition. And this is the first time that any piece of real estate in Cleveland has been a topic for this annual design challenge that is now older than some of its contestants.

This is a terrific opportunity for the power station site and for Cleveland. The site became a development opportunity on Cleveland’s lakefront after a First Energy power plant was razed in 2017 and the land was bought in 2023 by a company that repurposes former power plants sites. NEOtrans was first to report on the property acquisition.

In the competition. finalists included two design teams from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), a team from Harvard University in partnership with MIT and a team from the Georgia Institute of Technology. Achieving the status of finalist means the worst that each of these teams will do is win $10,000. The winning team will garner $35,000. Another $10,000 will be divided among four honorable-mention teams.

Each of the finalists offered ambitious proposals, ranging in scale from a capital investment of roughly $350 million to as much as $3.6 billion. Not only did they include new streets and buildings, but affordable and market-rate housing, public spaces and more.

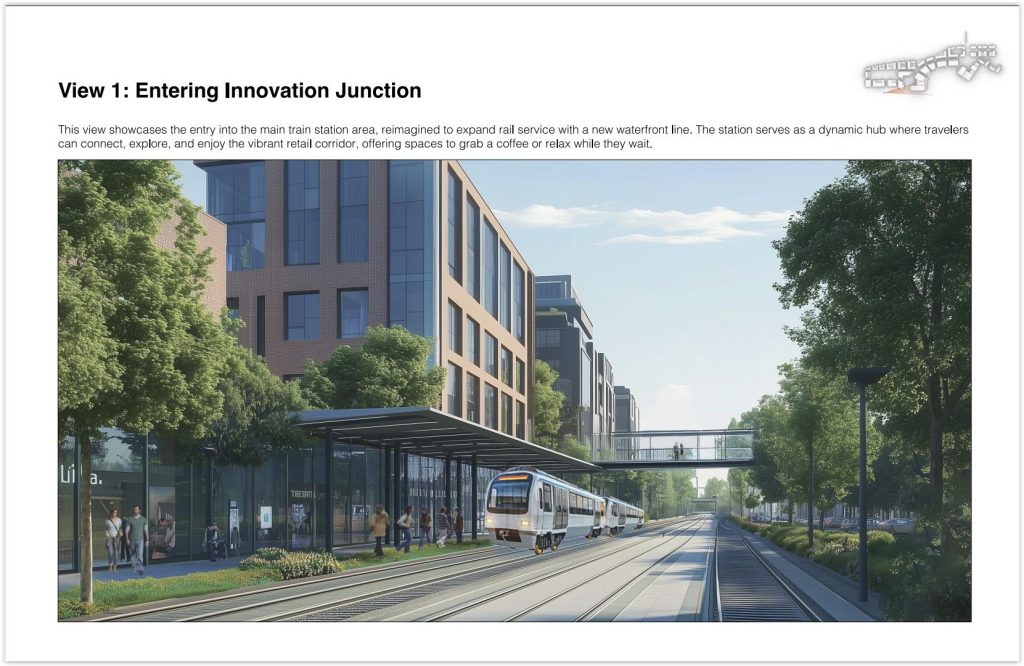

Linkages were proposed across Interstate 90 to Lake Erie to the north and across the CSX tracks to the St. Clair-Superior neighborhood to the south. Two entries proposed an extension of the light-rail Waterfront Line to the development site. And all proposals were required to have a pro forma showing project costs and financing to pay for them.

Cleveland was selected to be the host city after a selection process run by ULI, said Paul Beegan, CEO and founder of Lakewood-based Beegan Architectural Design. He is also chair of the ULI Cleveland District Council. The local council had to present several sites to the review committee. The Lake Shore Power Plant site was selected for a variety of reasons.

“I think this site is representative of many of the challenges facing the many cities of the Midwest Rust Belt as we work our way through the post-industrial transformation to a knowledge- and service-based economy,” Beegan told NEOtrans.

“All of our cities have many sites that were built to service an industrial economy that are no longer needed for that purpose and require remediation to repair the environmental impacts from that industrial past,” he added.

With the permission of the site’s new owner, an affiliate of Utah-based Industrial Development Advantage LLC (IDA), ULI chose the 62-acre site of the former Lake Shore Power Plant, 6800 S. Marginal Rd. Another 4 acres of city land bank land immediately to the west was also included. A hill at the center of the power plant site was considered off-limits, however.

Beegan said that, not only was the property owner involved in this competition, as is required for all sites in this competition, but so were the city and county planning departments as well as the Cleveland Metroparks. Last year, a site in Seattle was the competition’s subject.

He said the Cleveland power station site has unique advantages and challenges. The advantages are its lakefront location where the city, port and the Metroparks have planned massive projects with the East 55th Street marina, Gordon Park and the $300 million Cleveland Harbor Eastern Embayment Resilience Strategy (CHEERS) project.

The site also has greenways along Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard to connect the cultural, educational and medical centers at University Circle north to the lake. And if redeveloped, the former power plant property can connect the neighborhoods to the south back to the lake despite its challenges.

Those challenges include the site being hemmed-in by Interstate 90 to the north and the CSX railroad tracks to the south. But so was another on the other side of town.

“On the west side, Battery Park is an excellent case study of the potential this site has to do the same on the east side,” Beegan said.

Battery Park, located just south of Edgewater Park in Cleveland’s Gordon Square neighborhood, was built on the site of the demolished and cleaned-up Eveready Battery plant property that was heavily polluted.

That site was reconnected to Lake Erie by redesigning the Shoreway and building new road plus pedestrian links under the highway and railroad tracks. More than 1,000 housing units were built in and near Battery Park in the past 20 years with hundreds more planned.

Locally, three teams, each drawing students from Kent State University (KSU) and Cleveland State University (CSU), partnered in submitting entries. CSU Master of Urban Planning and Development graduate student Angelina Bair assisted one of the KSU-CSU partnering teams in applying.

“This is a major competition with submissions from urban planning students from all over the world,” Bair said. “No reaction information was given (by the judges) to the student teams. We worked with a mentor and project team leaders during the design process.”

Site plan for Harvard’s “Lakeshore” entry into the Urban Land Institute’s Hines Student Competition (Harvard-ULI).

This is the 23rd year of the annual ULI Hines competition. ULI is an international organization of real estate professionals including developers, builders, brokers, financiers, attorneys and, of course, architects.

Late ULI leader Gerald D. Hines, founder of the Hines real estate organization of Houston, created the competition with a $3 million endowment after he received the ULI Prize for Visionaries in Urban Development in 2002 but turned down its award money.

To compete, graduate or fourth-year undergraduate students form multidisciplinary teams and engage in a challenging exercise in responsible land use. Teams of five students pursuing degrees in at least two different disciplines have two weeks to devise a development program for a real, large-scale site in a North American city. Teams provide graphic boards and narratives of their proposals guided by faculty and professionals.

The first MIT team proposed “CLEarwater” — a $979 million, four-phase development with 2,214 housing units and extends Addison Road north to the lake. Planned was a high-density mixed-use zone, including creative office, light industrial makerspace, and retail spaces along the main corridor.

The two city-owned parcels were proposed to be transformed into the Clearwater Innovation and Media Hub to provide educational opportunities through partnerships with the existing Horizon Science Academy, Fox TV and Ohio Third Frontier.

The second MIT team submitted “The Anchor District – Where the Blue Future Begins.” This four-phase, $3.6 billion development offers 2,078 residential units, daycare facilities, grocery stores, shopping and dining centers.

A job training facility for the blue economy and 250,000 square feet of open greenspace would be provided. Addison would be continued north on an arc through the site and the Waterfront Line extended alongside the CSX tracks.

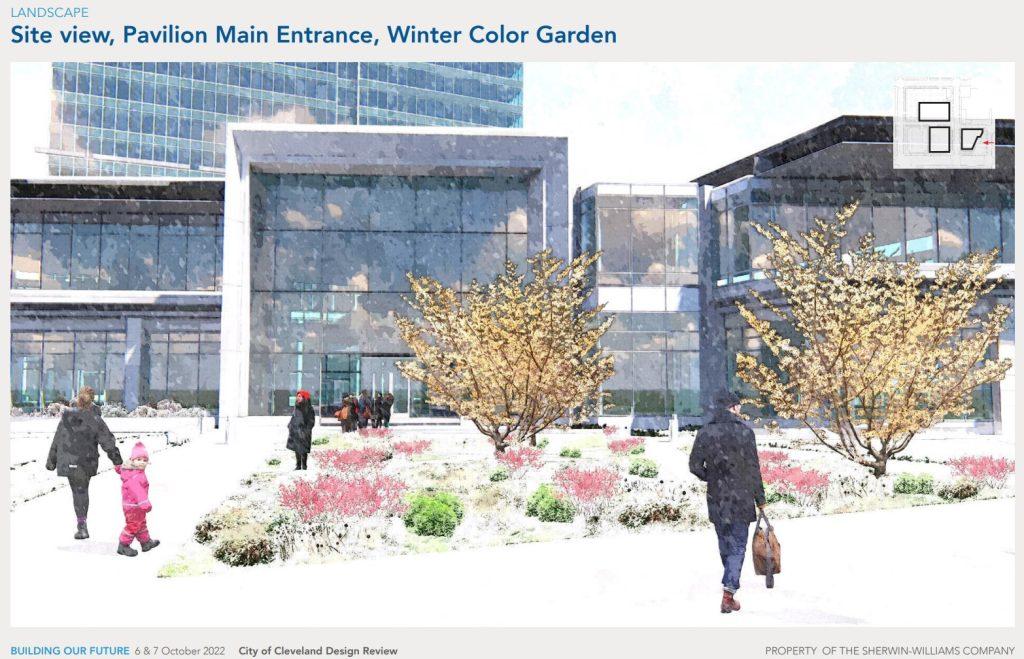

Harvard University’s “Lakeshore” is a three-phase, 2.25-million-square-foot, $1.3 billion development project. Lakeshore features a Community Ownership Trust to allow residents and small business owners fractional ownership and profit sharing.

Planned are 1,718 residential units and winter-city design principles that promote year-round vitality with protected pedestrian networks and flexible indoor-outdoor spaces. A central promenade connects entertainment and cultural nodes to a new rail station.

Georgia Institute of Technology proposed “ANCHOR” — a $347.8 million three-phase development that creates a mixed-use town center, accessible lakefront, and fosters diversity of housing and opportunities to act as an economic and social anchor for Cleveland. Addison is extended to create a main street to link with existing bus routes and is lined 623 housing units and a Maker District to grow local talent.

Just last week, NEOtrans wrote about the Lake Shore Power Station site, noting that the owner IDA had proposed a variety of potential end uses, some of which were met with opposition by a lakefront advocacy group. But it will be a long time before any development can occur here, as the site won’t be cleaned and cleared of its few remaining structures and cooling ponds until 2028, the owner IDA said.

“IDA is evaluating potential redevelopment options for the property which may include commercial/industrial uses such as ground-mounted solar facilities; battery energy storage facilities; telecom or data centers; and retail, entertainment, residential and/or a mixed-use consisting of residential and commercial development,” the company said on its newly created Web page about the former Lake Shore Power Station.

END