UPDATED DEC. 16, 2020

One of the last surviving Euclid Avenue mansions is facing possible demolition to make way for a significant mixed-use real estate development by a national developer. It is one of several real estate developments popping up in the area.

Known by historians as the Allen-Sullivan House and more recently as The Colosseum, the 1887-built house at 7218 Euclid became the subject of a demolition permit application submitted to the city of Cleveland today.

The application was submitted by C&J Contractors of Cleveland on behalf of Signet Real Estate Group, according to public records from the city’s Building Department. A demolition permit request was also submitted to the city for a neighboring car repair shop at?7224 Euclid. Signet’s principal offices are located in Akron and Jacksonville, FL.

Signet acquired the mansion and nearly 6 acres of land in the 7200 block between Euclid and Carnegie avenues on Oct. 1 for $2.4 million, according to Cuyahoga County records. Six acres is a very large development site for an urban area. For reference, the property on which the Rocket Mortgage Fieldhouse (home of the Cleveland Cavaliers) sets is just under 7 acres.

Although Signet’s development plans are still at an early stage, the firm is reportedly seeking to develop primarily residential uses with some commercial space along Euclid and/or Carnegie, according to a source who spoke off the record because he was not authorized to speak publicly about the project.

The source said that Signet’s primary interest is to first develop the southern part of the site, near Carnegie. The demolition request for the mansion was submitted now because the city apparently has a backlog of permits to process and is taking a long time. So a demolition does not appear imminent as a development concept for the Euclid end hasn’t been nailed down, the source said.

Signet typically develops institutional structures such as for hospitals, universities and research centers plus carrying out public-private partnerships involving port facilities, sports stadiums and parking garages. But it also develops student housing for institutions of higher learning.

Its most recent housing project in Cleveland was the Axis at Ansel. Opening this past summer, the $35 million, 163-unit apartment building with more than 1,000 square feet of street-facing retail is located at the corner of Ansel Road and Hough Avenue.

Joel Maas, Signet’s director of marketing and communications, acknowledged receiving an e-mail from NEOtrans seeking more information about the project but didn’t otherwise respond prior to publication of this article. Jeff Epstein, executive director of MidTown Cleveland, refused to comment about the project or the requested demolition.

According to the two demolition permit applications, the cost to raze the targeted structures and remove their debris is estimated at $120,000. That includes the 14,300-square-foot auditorium/fraternal hall built in 1935 behind the 5,600-square-foot Allen-Sullivan mansion. Cuyahoga County property records rated both structures as being in “very poor” condition.

Kathleen Crowther, president of the Cleveland Restoration Society, told NEOtrans that the Allen-Sullivan mansion isn’t a designated Cleveland landmark. So, unfortunately, its demolition will not be reviewed by the Cleveland Landmarks Commission.

“It is sad to lose yet another Euclid Avenue house,” she said. “I understand from the city that it was likely eligible as a landmark. However, the property appears to have been severely underutilized for many years now, which would mean deterioration that accelerates with time.”

Crowther noted that with the recent establishment of Opportunity Zones and this property’s inclusion in one, the mansion has become the target of real estate investors in the past year. Coupled with the growth of nearby University Circle, it was only a matter of time before the neglected mansion fell victim.

“It is not surprising to hear it has changed hands,” she added. “It is in our community’s best interest to preserve landmarks when it is economically feasible, which often times it is due to the federal and state tax credits for historic property redevelopment. If a property like this is demolished, we believe that the replacement development should have to provide a higher community value.”

| The Fisco family operated The Colosseum party center for 35 years until 1999. It has sat vacant ever since except for a caretaker who reportedly lived at the once grand mansion (Bill Blasko). |

The house and the fraternal hall have sat unsed for 20 years except for an on-site caretaker, wrote historian Jim Dubelko at ClevelandHistorical.org. The Queen Anne-style house was built in 1887 by railroad industry supplier Richard Allen and his wife Susan. As a widow, Susan Allen sold it in 1898 to Central National Bank founder Jeremiah J. Sullivan.

After the Sullivan family moved out, the mansion served from 1923-31 as an upscale furniture store called The Josephine Shop. In the midst of the Great Depression, the house was sold to the The Grand Lodge of Ohio, Order Sons of Italy in America which converted it in 1935 into an Italian-American fraternal hall. It included adding the auditorium onto the back of the house, Dubelko wrote.

The fraternal organization sold the Allen-Sullivan mansion in 1946 to the American Society of Heating and Ventilating Engineers. It operated offices and a research laboratory on the site until 1961, when the facilities were closed.

Dubelko wrote that it was sold again, this time in 1964 to Mary Fisco whose Italian immigrant husband Benjamin restored the house and auditorium to its appearance when it served as the Italian-American fraternal hall and operated it as The Colosseum Entertainment Center. Seven years after Benjamin Fisco’s 1992 death, the Colosseum closed and went through five ownership changes in the next 20 years.

“Given this owner’s desire to sell, and the City of Cleveland’s desire to continue redevelopment of its Midtown Corridor along Euclid Avenue, the future of the Allen-Sullivan house is precarious and it might not avoid demolition without an effort on the part of the city and/or the future developer to save it” Dubelko wrote several years ago.

END

- New downtown park with basketball court fast-tracked

- Michael Symon joins River Roots’ move to Flats

- Tenant ID’d for big new industrial development near Hopkins airport

- $119M Lakewood Common project goes vertical

- CWRU to renovate, expand one of its most historic buildings

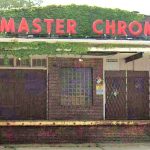

- Master Chrome coming down, cleaning up