As Cleveland City Council prepares to vote soon on rezoning more former industrial land to residential near Edgewater Park, there are fewer lakefront industrial areas on the west side. One of those may succumb to the inexorable march of residential expansion after another expected rezoning that could enable high-rise development.

As early as next week, council may rezone an area south of Edgewater Park from general industrial to a residential classification. This area is centered around West 70th-73rd where the Eveready Battery Co. plant once stood. Razed and remediated in the 2000s, the land was redeveloped with mostly housing and renamed Battery Park.

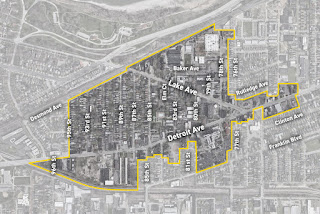

Council’s vote is expected to follow action last week by the City Planning Commission to support rezoning former industrial land south of the Shoreway, north of Lake and Detroit avenues. Some of the zoning fixes extend as far west as West 78th Street, said Ward 15 Councilman Matt Zone.

“It’s consistent with a long community planning process,” Zone said in an interview this week. “In 2015 and 2016, we did a Gordon Square Arts District masterplan that calls for transitioning the semi-industrial use to housing. So now we’re just moving the legislation forward.”

|

| City Council could vote as early as next week on this pro- posed zoning change that will reflect the development of former industrial areas into residential ones (CPC). |

Adam Davenport, neighborhood planner for the city, said the semi-industry zoning classification that was left over from the Eveready Battery plant was preventing residents of the new developments from getting home loans.

“The new zoning will be two-family,” Davenport said. “That will allow people to get financing or refinancing from lenders.”

Another change was to remove resident industry zoning near Detroit Avenue and replace it with a multi-family designation. Davenport said that “resident industry” is an archaic classification, dating from when offices and residential abutted industry and especially smaller tool and die shops that had low impacts from emissions or noise.

Zone said it took so long to get the rezoning in place because the City Planning Commission was overwhelmed with other work. That includes a new form-based zoning code pilot project. A form-based code is a new approach to zoning with an increased focus on walkability, predictability and mixed-use development.

Immediately west of Battery Park and east of the Edgewater and Cudell neighborhoods is one of the last industrial areas left on the West Side’s lakefront. Rezoning this area with a Euclidean, use-based zoning classification such as multi-family wasn’t desired because it would force out active, viable businesses, Zone said.

But the use of a form-based code in this area would allow for either industrial or residential in this area, bounded by Detroit and Lake avenues, the Shoreway and West 78th, Davenport said.

“Form-based zoning can talk about industrial and residential,” he said. “It’s based on what you see.”

This industrial area is the northern reach of a west-side pilot program to introduce form-based zoning to Cleveland’s zoning code. Two east-side areas are also part of the city’s pilot program — the Opportunity Corridor and parts of Hough and Glenville. City officials said they hope to get a draft code in place by fall.

Although the industrial area included in the west-side form-based code pilot can stay industrial after the pilot starts, the expanding residential development nearby may ultimately move in. The form-based code would allow for that, too.

There are reportedly no proposals to uproot viable employers like Alcon Industries, Universal Grinding, Lowe Chemical or Mid-American Construction. Some of these companies’ facilities are more than a century old, such as Lowe Chemical’s well-maintained, three-story, 112-year-old brick structure at 8400 Baker Ave.

Yet others were built as recently as 2016 such as Alcon’s 30,000-square-foot expansion at 7990 Baker, according to Cuyahoga County property records. Alcon is the largest employer in this neighborhood with roughly 175 employees.

The fates of these industrial properties could change in the coming years, however. For that to happen, it would require real estate investors and developers with deep pockets to afford buying, demolishing or converting and cleaning the industrial sites.

Given those expenses, the only type of residential development that might be justified for that area are large-scale buildings that produce lots of revenues so that developers could recoup their site acquisition and preparation costs — in other words, high-rise housing.

“I don’t know why it wouldn’t be justified because that’s on the bluff overlooking the lake and the park,” Zone said. “Before that happens, we would have to engage the community.”

A metamorphosis of the industrial area into new uses actually began in the 2000s with the conversion of the 1905-built Baker Electric Motor Vehicle Co. factory at 1300 W. 78th into the 78th Street Studios. Today it is the largest fine arts complex in Northeast Ohio, hosting 60 arts studios and galleries, an internet radio station and a theater.

“The writing is on the wall for the (lakefront) industrial area,” Davenport said. “It’s going to be quite the area for new construction.”

END

Comments are closed.