Haslam Sports Group, owners of the Cleveland Browns, seek construction of this landbridge and conversion of the Shoreway into a boulevard to better connect downtown with the lakefront. That and inclusion of a multimodal transportation center within the landbridge would support development of the lakefront with public spaces, housing, hotels, offices, shops and restaurants (AoDK). CLICK IMAGES TO ENLARGE THEM

City, residents, Browns want traffic slowed; ODOT doesn’t

The fate of lakefront development in Cleveland appears to depend on whether local, regional and state policymakers want more traffic and for it to pass through downtown quickly or to have less traffic and for it to travel into the central business district more slowly.

On one side, city officials like Mayor Justin Bibb and Ward 3 Councilman Kerry McCormack, downtown residents and the Haslam family, owners of the Cleveland Browns, want the city’s oldest freeway to no longer be barrier between downtown and the lakefront. Instead, they want the Shoreway (State Route 2) to become a boulevard that people can cross on foot or on bikes and along which new housing and businesses can be built.

In short, they want roads to get people to the city to conduct commerce as roads have done for thousands of years — not to follow the theories of Norman Bel Geddes that were echoed by General Motors and Shell Oil starting in the 1930s — the decade the Shoreway was built. Geddes, the industrial designer and author of “Magic Motorways,” espoused “There should be no more reason for a motorist who is passing through a city to slow down than there is for an airplane which is passing over it.”

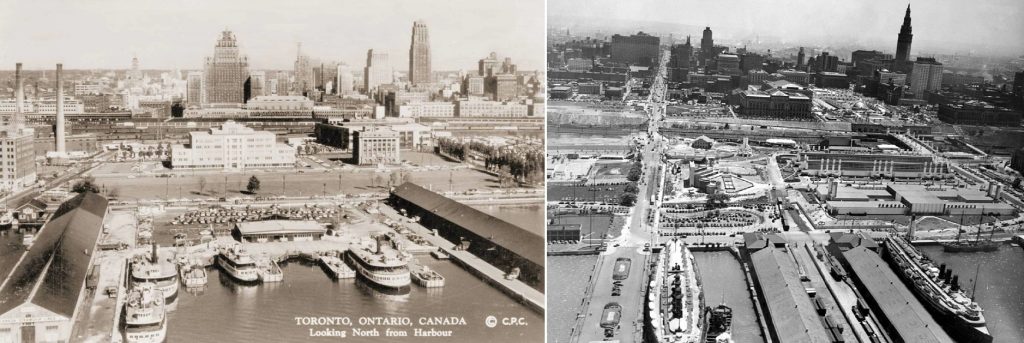

Until the 1960s, Toronto (left, in the 1950s) and Cleveland had comparable lakefronts, populations and skylines. Both of their lakefronts were bustling with passenger and freight shipping but, outside of the 1936-37 Great Lakes Exposition (shown at right) and the 1932-built Cleveland Municipal Stadium just out of view to the right, Cleveland didn’t introduce public spaces or develop its lakefront like Toronto eventually did (CPC, CSU).

Highway engineers have been chasing that elusive dream ever since, demolishing more and more of our cities in deference to the car but to no avail. Yet Geddes’ policy continues to be followed today. In order to receive federal funds for a highway improvement project, the predicted outcome of that project must be to increase the fluidity of traffic, as determined by a qualitative measure called Level Of Service (LOS).

However, only recently have highway engineers acknowledged that bigger, faster, free-flowing roads only induce more traffic and make cities less livable. Transportation and urban planners have learned that car dependency can also negatively affect a broad range of policy issues — environmental and climate protection, community integration, neighborhood equity, public health and safety, land use, business growth and access to jobs.

So the city of Cleveland, the Ohio Department of Transportation (ODOT) along with the Northeast Ohio Areawide Coordinating Agency (NOACA) which distributes federal transportation funds to Cuyahoga, Geauga, Lake, Lorain and Medina counties are conducting a feasibility study of removing the Shoreway between the east end of the Main Avenue Bridge at West 9th Street and a location just west of the existing Dead Man’s Curve on Interstate 90. The curve is to be realigned starting in 2025.

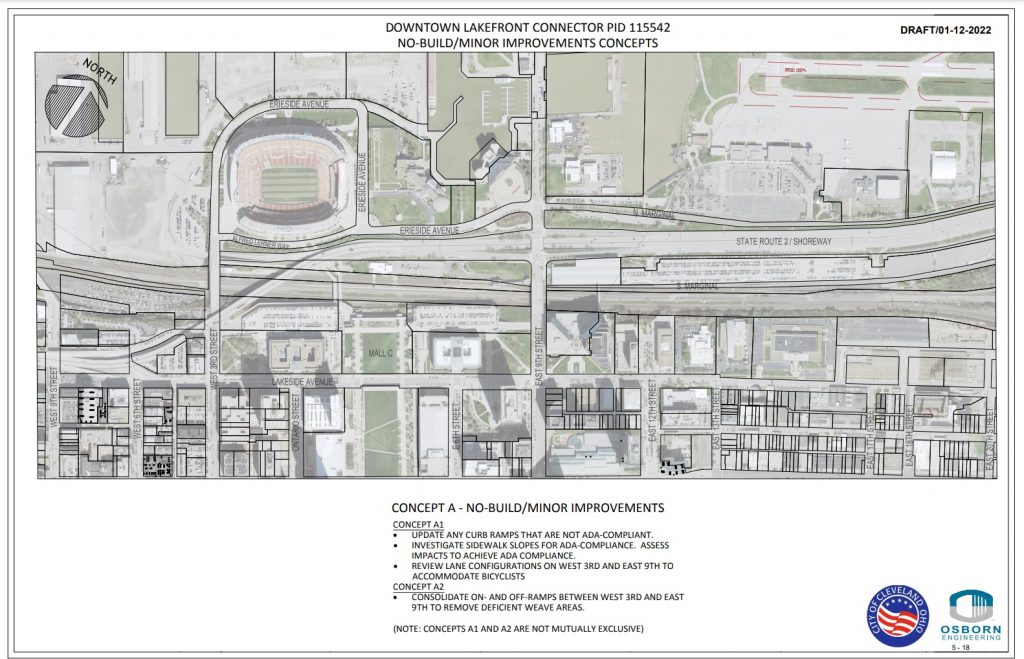

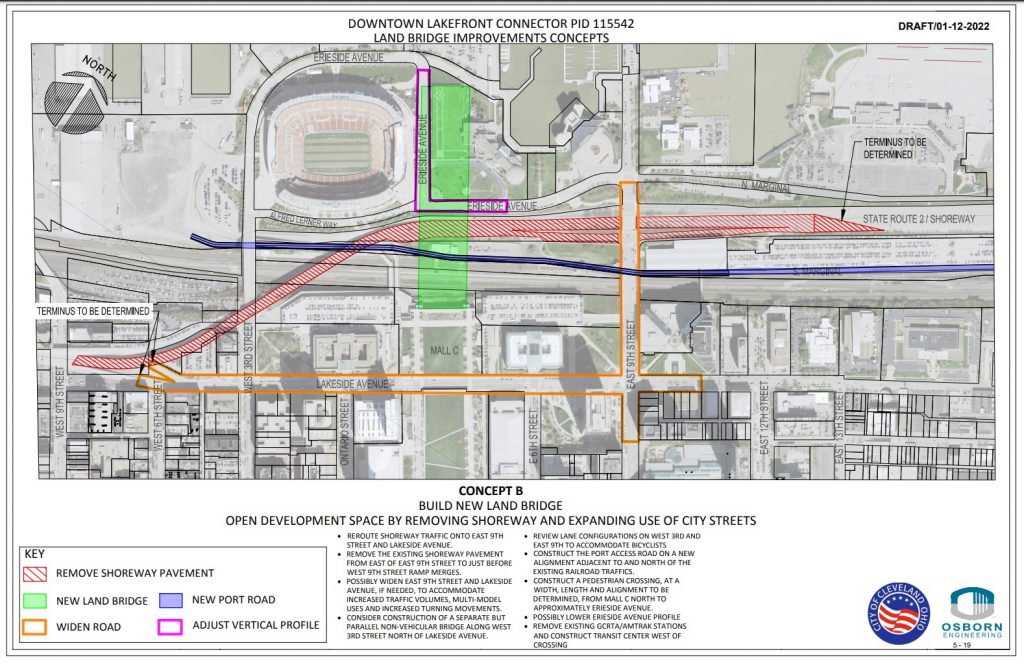

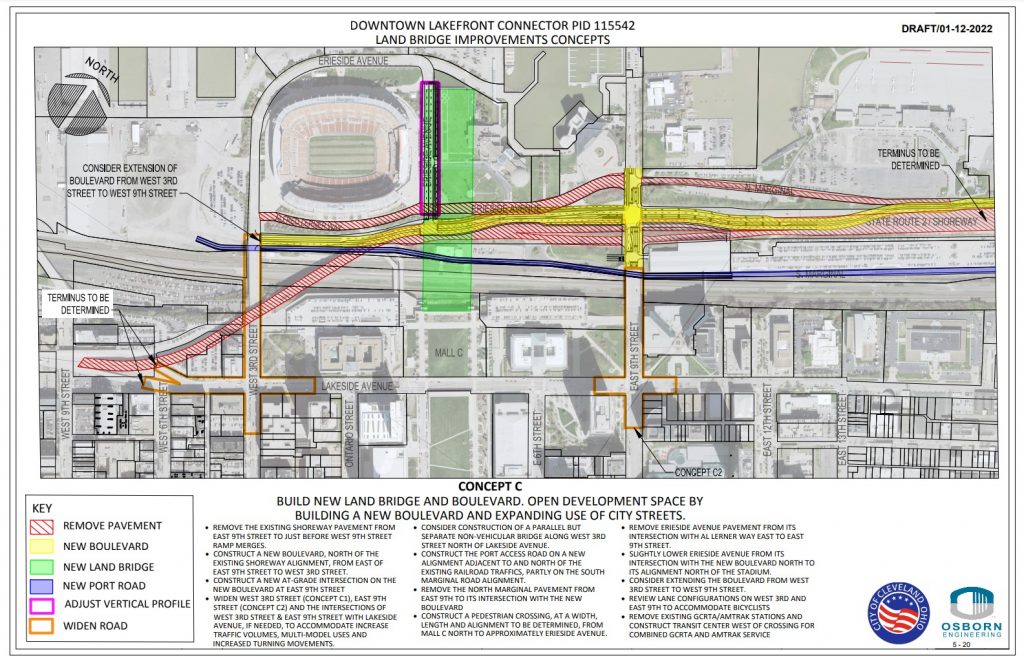

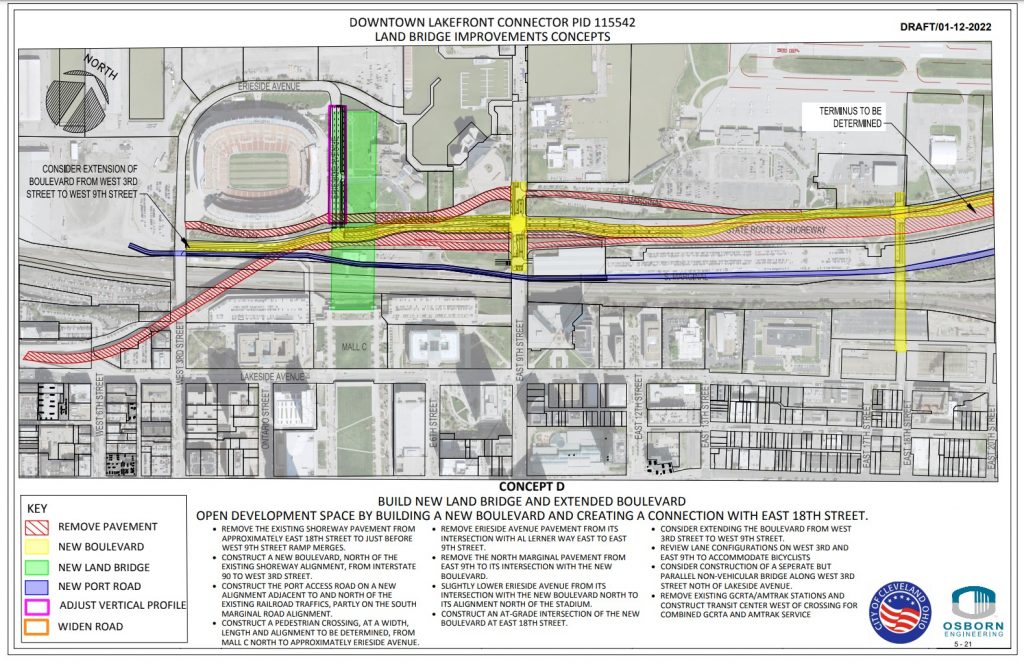

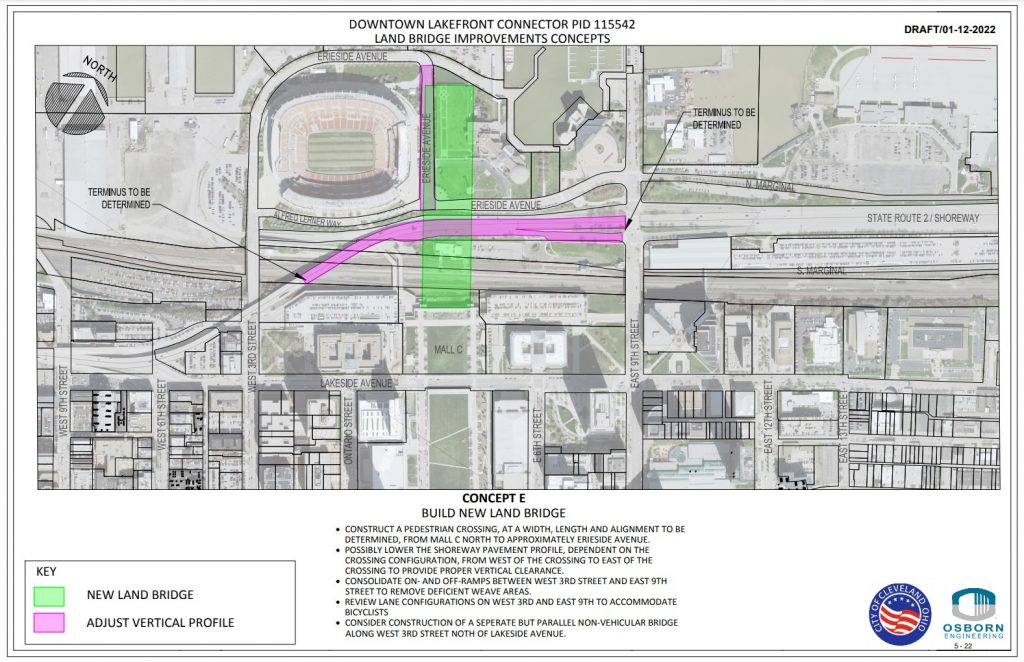

Study team members developed five alternatives to study (click here and start on Page 51), including doing nothing to gather a baseline of data. Three of the alternatives proposed replacing the Shoreway with a boulevard through downtown. Another option proposed replacing the Shoreway bridge east of West 3rd Street over the railroad tracks with a lower one.

The study is in response to planned lakefront development by the Haslam Sports Group, owners of the Cleveland Browns. Their plan centers on a proposed land bridge over the lakefront railroad tracks, a port access road and a boulevard that could replace the Shoreway. The land bridge would provide enhanced pedestrian and bicycle access between downtown and the lakefront as well as to link public spaces offered by the downtown malls and North Coast Harbor.

But a NOACA staff review criticized the feasibility study’s methodology, developed by the city’s Traffic Engineer Andrew Cross and ODOT as being too focused on how it will affect motorists. Neither Cross or ODOT’s District 12 public information office responded to e-mails requesting comment prior to publication of this article.

“The feasibility study to narrow down the presented alternatives seems to rely heavily — perhaps only — on the results of the traffic capacity analysis and intersection LOS results,” NOACA’s staff review said. “Criteria for narrowing down the alternatives should also include other criteria related to safety, bicycle level of traffic stress, multimodal connectivity, economic development.”

During his campaign last year, Mayor Bibb, a former executive at an urban technology nonprofit and a former member of the Greater Cleveland Rapid Transit Authority (GCRTA) board of trustees, said he wants every Cleveland neighborhood to prioritize pedestrians over cars. “People over cars” became a campaign slogan for him and was supported by multiple councilpersons.

“For far too long, we’ve let the almighty car dictate how we build and design our cities,” said Councilman McCormack whose ward includes downtown and the near-west side. He said he supports replacing the Shoreway with a boulevard. “If we are at all serious about creating a more vibrant Cleveland that connects our city and our people to our most precious natural resources, these are changes that need to be made. If we make a decision based on how fast can I get around and through the city, it will be a 100-year mistake.”

Federal funding resources that could be tapped for this project include the Jobs & Commerce Economic Development (JCED) program which is managed in Ohio by ODOT. Another possibility is the recently passed federal infrastructure law which contains a new program for removing highways that have divided communities and discouraged economic growth. It was originally intended to be funded at $20 billion but was scaled back to $1 billion. Neither program may require improved LOS results for a project to win funding.

Alan O’Connell, president of the Downtown Cleveland Residents, a community relations board, said his group favored the landbridge’s Concept D although he said he would like to see the landbridge widened to cover more of the tracks that belong to GCRTA and Norfolk Southern. GCRTA’s tracks are for the light-rail Waterfront Line whose service is currently suspended for a year or two because a bridge over the NS tracks needs repairs. NS runs about 70 freight trains a day on its tracks and hosts Amtrak’s nightly passenger rail services to Chicago and the East Coast.

“Overall, the downtown community fully supports Concept D as we have been pushing for a transformation exactly like it for many years,” O’Connell said. “I would love to learn a little more about how the landbridge navigates the elevation change down to the lake and what happens when it intersects the proposed boulevard. Does the boulevard go underneath the park there? I’d also love to see that little bit of the ‘new’ East 18th Street extending northward into Burke (Lakefront Airport). We all know it cannot remain an airport forever.”

Concept D proposes constructing the landbridge, removing the Shoreway downtown, constructing a port access road, combining Amtrak and RTA services in a new station, building a new boulevard and extending East 18th Street north to the new boulevard to ease traffic and develop the Campus District (Osborne).

Mark Lammon, executive director of the Campus District Inc., a community development corporation for the east side of downtown, said he was happy to see the inclusion of East 18th Street to the Shoreway boulevard in Concept D.

“Campus District has advocated for a northern lakefront connection in the district for years,” Lammon said. “This proposal has the opportunity to accomplish the goal of creating a multimodal connection to the lakefront.”

Dick Clough, executive board chair of the Green Ribbon Coalition, Inc. which promotes lakefront public improvements including better access, also had questions about the concepts. His organization originally proposed the landbridge that the Haslam Sports Group has since adopted, but the coalition’s version of it angled the bridge northeastward so the Shoreway didn’t have to be significantly altered. But that may also depend on the future of the Shoreway’s 1939-built Main Avenue Bridge over the Cuyahoga Valley.

“I don’t think any conversation or study can be undertaken without exploring alternatives for also replacing the Main Avenue Bridge which is nearing or past its 80-plus-year design expectation,” Clough said. “A new bridge with approach ramps could address harbor access sufficiently to afford the necessary clearance to accommodate the landbridge concept proposed by the Browns. The coalition would also be supportive of relocating the Amtrak station and combining it with RTA’s Waterfront Line as suggested in the harbor traffic study. A multi-platform transit and rail facility is the the right idea.”

The study proposes replacing GCRTA’s West 3rd and East 9th Waterfront Line light-rail transit stations with a new multimodal station. The nonprofit rail and transit advocacy group All Aboard Ohio said the multimodal station should be served by Amtrak, Greyhound and transit bus services to surrounding counties, possibly using the port access road. These and other aspects of the city’s feasibility study were discussed at a NOACA Planning Committee meeting Monday where stakeholders also agreed the location of the existing light-rail and Amtrak station facilities were less than ideal.

“To put a multimodal station closer to the Browns stadium, underneath the landbridge whose goal is to promote walking, is a good idea,” said Stu Nicholson, executive director of All Aboard Ohio. “It creates an overhead shelter. We need a better Amtrak station and an improved Waterfront Line that could potentially become a Downtown Loop. The thing that makes me that much more enthusiastic is that the owners of the Browns favor that plan. It makes it more realistic.”

He added that the Shoreway-redesign concepts outline some very intriguing traffic patterns, including moving traffic into downtown where people could stop and patronize businesses. There were recently up to 40,000 vehicles a day that traveled on the Shoreway, especially west of downtown. However that number may have decreased following the opening of the Opportunity Corridor which could have pushed some traffic to I-90, O’Connell added. McCormack concurred.

“We have multiple other freeways that connect you to and through downtown,” McCormack said. “So if we want, we can also open up the conversation of smart city technology. It’s something I’ve been talking about for years. Let’s use technology to better assist the city to move traffic.”

Numerous other cities in the USA are seeking to eliminate highways and, in most cases, replace them with pedestrian-friendly boulevards surrounded by parks and/or new development. Great Lakes cities are removing highways because most of these communities have less population and traffic than what their roadway system was designed to handle. So shrinking them to reduce their costs of upkeep and to promote economic development have won community support. In some cases, local planners took over these efforts from state highway departments that were reluctant to remove highways.

Here are some of the cities near the Great Lakes that are removing highways or replacing them with boulevards:

Akron — City officials championed removal of State Route 59/Innerbelt southwest of downtown for a new boulevard, park and restoration of the Oak Park neighborhood. Work began in 2017.

Buffalo — Several highways are being considered for removal and/or replacement with boulevards and expanded parks along the lakefront and at Delaware Park, including the Scajaquada Expressway, the elevated lakefront Skyway and Kensington Expressway.

Detroit — Replacing a six-lane I-375 north of downtown with an eight-lane boulevard was proposed by the Michigan Department of Transportation but local officials said the new road would be too wide.

Milwaukee — Park East Freeway was demolished in 2002 and replaced with McKinley Boulevard plus a restored street grid to promote economic development near the Milwaukee River.

Rochester — City officials led the effort to remove and fill in the Inner Loop East highway to promote economic development on the east side of downtown. The rest of the Inner Loop may be removed, too.

Syracuse — The I-81 viaduct through downtown will be replaced with a boulevard and I-81’s designation and traffic are being relocated east of the city to I-481.

END

- Michael Symon joins River Roots’ move to Flats

- Tenant ID’d for big new industrial development near Hopkins airport

- $119M Lakewood Common project goes vertical

- CWRU to renovate, expand one of its most historic buildings

- Master Chrome coming down, cleaning up

- Familiar Ohio City buildings go on sale for the first time in 143 years

Comments are closed.