Climate change, remote work, affordability move migrants

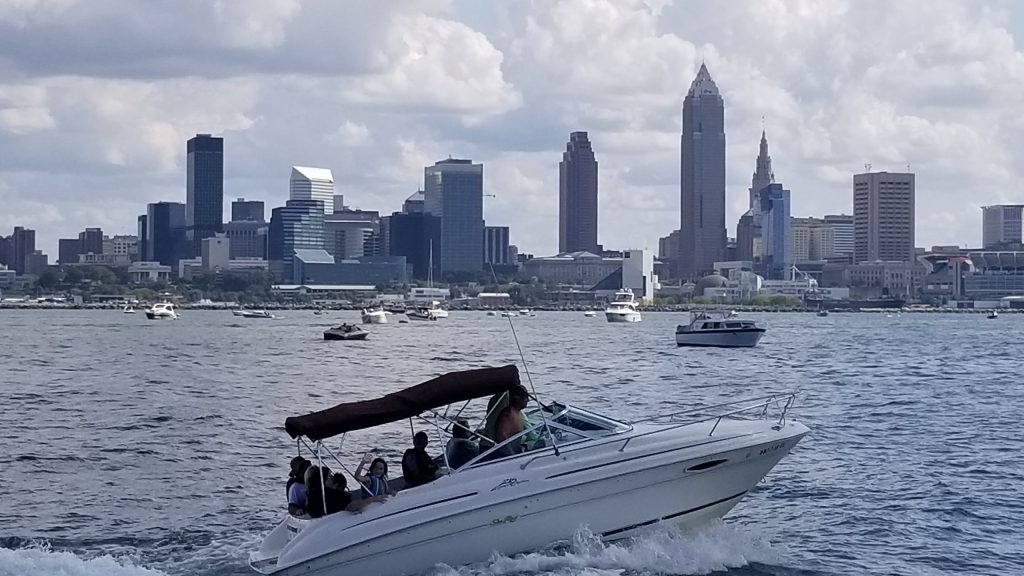

One of North America’s next big migrations may already be underway. And according to early data, it appears that Cleveland and other Great Lakes cities are among those benefitting from it. What’s driving this new migration? The basics — low cost, proximity to family, abundant fresh water and peace of mind from not worrying about your neighborhood catching on fire or washing out to sea.

Those are all things that Greater Cleveland has to offer. And even if you don’t have family here, that familial Midwestern friendliness can help make up for it. But those basics are combining to produce data that shows something compelling and potentially historic is developing.

According to Reventure Consulting, a Dallas-based real estate data consulting firm, a crash of the housing market may be underway in the western states and, to a lesser extent, the southern states. Reventure founder and CEO Nick Gerli also pointed out that, while housing prices have fallen by 7-17 percent in metro areas in the West from May to October of this year, they are still appreciating in Northeast and Midwest metro areas. Gerli said he anticipates western/southern housing prices will fall further, possibly by 20-30 percent over an entire year, although panic selling hasn’t yet occurred.

“My read of this data: there’s a big migration shift taking place in America right now that NO ONE is talking about,” Gerli wrote on Twitter. “It’s an exodus out of the western half of the country into the Northeast/Midwest. Basically a complete reversal of the previous 30 Years of migration trends.”

He said states like California, Utah, Colorado and Oregon are no longer as desirable given their high costs of living and climate issues, especially their chronic drought conditions and worsening wildfires.

“Don’t be surprised if values here crash…by a lot. And for a long-time,” Gerli added. “Rust Belt states like OH, PA, and NY hold their value better.”

And who would have ever thought Cleveland’s weather would be a draw to residents? For all its faults, Cleveland’s weather never burned down thousands of acres, inundated coastal communities or threatened to dry up or salinate one of the most important things that all humans need to sustain their lives — fresh water. And Cleveland’s weather is moderating according to 30-year trends.

Our winters aren’t as long, cold and snowy as they used to be. The reason is that Cleveland’s climate today is in a zone that was located across southern Ohio and Kentucky 30 years ago. That can be tracked by the northward shift of an agricultural climate zone called the Plant Hardiness Zone by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA). Northern Ohio was in USDA Zone 5 until a 2012 update. Now it is mostly in Zone 6 (for reference, Alaska is in Zone 1, the Tropics are in Zone 13). And the zones are moving northward at 13 miles per decade, according to a report published in 2018 by Yale University’s School of the Environment with average air temperatures in the Great Lakes region rising 3-5 degrees Fahrenheit by 2050 and 6-11 degrees Fahrenheit by 2100.

Furthermore, the report notes that the arid Western plains of North America has historically met the continent’s wetter, eastern region near the 100th Meridian. This climatic boundary has shifted about 140 miles east since 1980, meaning the location of where cold, dry Canadian air collides with warm, moist Gulf of Mexico air has also moved. That has helped to push the most dangerous parts of “Tornado Alley” from an Indiana-Texas line southeastward into Dixie. And it means Ohio and especially Cleveland are less likely to see tornadoes than they did 30 years ago, and much less so when compared to the 1950s.

Perhaps half of the buildings visible in this aerial view above Euclid Avenue in University Circle’s Uptown section weren’t here 40 years ago. That’s demonstrative of the economic boom that has delivered tens of thousands of jobs to this area in that time frame and also attracted thousands of housing units, ranging from townhomes to apartments in high-rise buildings (Lance Aerial Media/UCI).

That doesn’t mean that the Great Lakes region is a utopia or will become one. Its annual precipitation has increased 13.6 percent since the 1950s, causing higher lake levels, shoreline erosion and stormwater runoff, according to Great Lakes Integrated Sciences and Assessments at the University of Michigan. The latter condition has resulted in more nutrients being washed into the lakes, feeding algae blooms which threaten the quality of drinking water, fishing, recreation and tourism. If allowed to worsen, it threatens the very thing that makes the Great Lakes region a refuge for people fleeing the effects of climate change elsewhere.

But what ultimately gets people to relocate in peacetime is economics. Being able to find a job and make ends meet is what brought large numbers of people to the Great Lakes region more than a century ago and that’s what is causing renewed migration to it now. Last year, NEOtrans wrote about the growing population of working-age adults in Cleveland and Cuyahoga County, the rising number of occupied housing units, the decreasing poverty rate as well as the increasing productivity of Cleveland and other Rust Belt cities compared to Sun Belt cities. That has resulted in Greater Cleveland adding jobs at a faster pace than many Sun Belt metros.

Remote working got a big boost from the pandemic and has helped make transitions less difficult for migrants. That boost was passed onto metro areas like Cleveland which offer lower costs of housing and living, making them attractive as remote-working hotspots. Also, people remote-working from more expensive cities often out-earn their peers in lower-cost cities, according to a report by Bloomberg. Cleveland was recently ranked as the best city in the country for home purchasing power.

And it is also a reason why, according to Realtor.com, the median sale price of a home in the city of Cleveland rose from $131,500 in June 2021 to $142,500 June 2022 before settling back a bit in the fall, as it tends to do each year although rising interest rates are surely taking their toll. In Cuyahoga County, median home selling prices grew from $200,000 in June 2021 to $213,000 one year later. Realtor.com considered Cuyahoga County “a seller’s market in September 2022, which means that there are more people looking to buy than there are homes available.”

Greater Cleveland often takes for granted its presence on the Great Lakes — a collection of freshwater inland seas that offer drinking water, recreation, fishing and international commerce. But those attributes not only support the lives of tens of millions of people, they can save the lives of many millions more (KJP).

The same thing held true for rentals, which accounts for half of the housing stock in Greater Cleveland and will likely increase in coming years. The reason why is because rents are rising faster in our metro area than any other urbanized region in Ohio and it ranks as one of the fastest growing rental markets in the nation, per Realtor.com. Greater Cleveland’s rent grew 9.8 percent in September 2022, compared to the same month one year ago. As with the for-sale housing market, rental markets are strongest in the Northeast and Midwest, while rents are not growing as fast or even falling in the West and South.

Real estate data and analytics firm Costar reported in August that apartment construction in Greater Cleveland is off the record highs it experienced from late-2021 into early-2022. Even so, the pace of construction is still very high. Preliminary third quarter 2022 data showed that construction of apartments was occurring at a much faster rate now than at any time in the 15 years prior to the third quarter of 2021. As with the for-sale housing market, rising interest rates were taking the edge off the blistering pace of constructing new apartments.

Michael Panzica, one of Greater Cleveland’s most active developers of apartments with recent developments such as the Baricelli Little Italy Apartments in Little Italy and Church+State in Ohio City, credits the remote-work hangover from the pandemic.

“Cleveland is benefitting from COVID and remote working,” Panzica said. “Why not live and work in a lower-cost city? People want to be near family and friends. That’s a trend I think will continue. Financing is the biggest cost challenge right now but rents are rising and offsetting those costs.”

END

Our latest Greater Cleveland development news

- Michael Symon joins River Roots’ move to Flats

- Tenant ID’d for big new industrial development near Hopkins airport

- $119M Lakewood Common project goes vertical

- CWRU to renovate, expand one of its most historic buildings

- Master Chrome coming down, cleaning up

- Familiar Ohio City buildings go on sale for the first time in 143 years