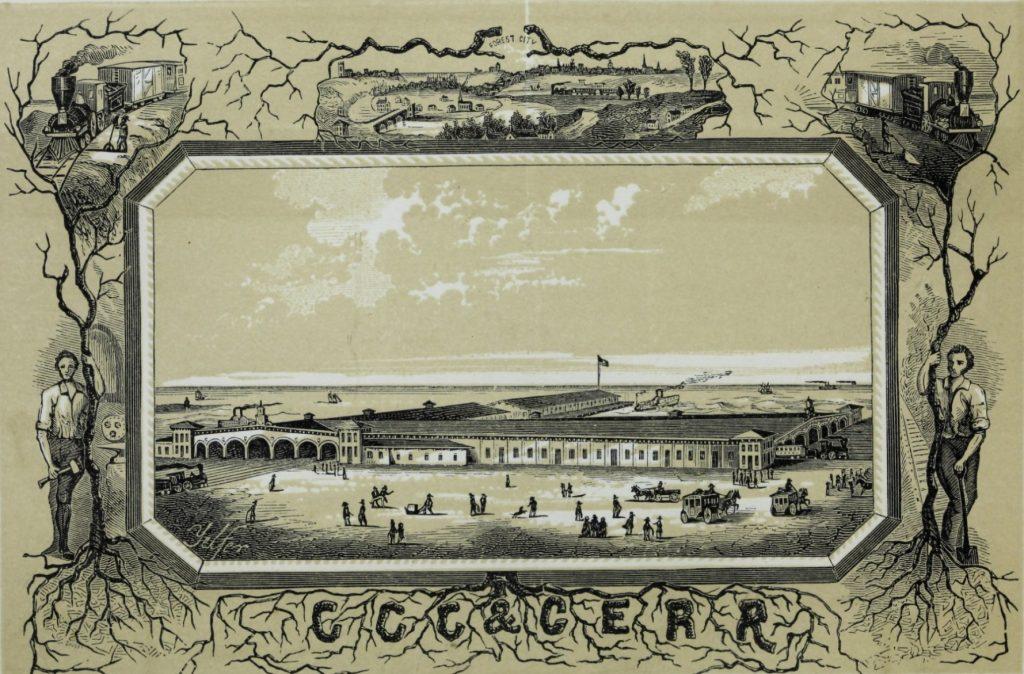

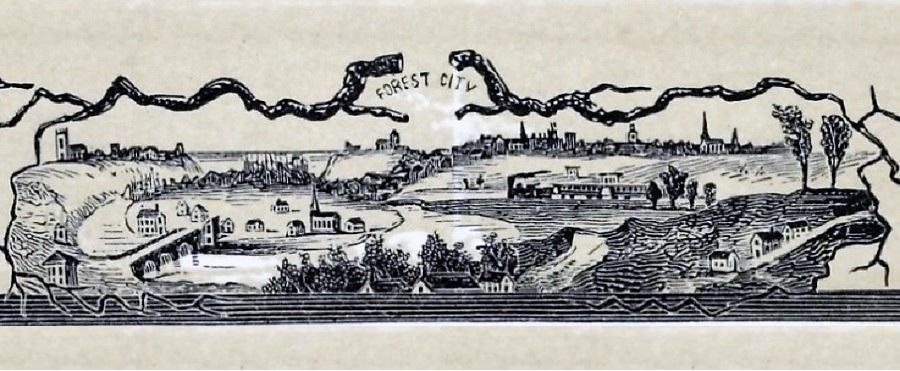

A placard from the Cleveland, Columbus and Cincinnati Railroad shows a proposed union station on Cleveland’s lakefront that would have included a steamship terminal as well. While a union station that united several railroads under one roof was built, it didn’t look like this. The placard emphasizes Cleveland’s emergence from being a wilderness outpost to a well-connected industrial center (WikiMedia Commons). CLICK IMAGES TO ENLARGE THEM

From trails to rails back to trails

On an early fall day, Sept. 30, 1847, one of the most prominent men in the fast-growing state of Ohio rolled up his sleeves and joined others in starting the construction of Cleveland’s first-ever railroad. It was a ceremonial groundbreaking not unlike those of today where dignitaries flip dirt with golden shovels to commemorate the start of some new construction project. But, in this case, Cleveland’s first village president, its first attorney and the father of the Ohio & Erie Canal had to get his hands dirty pronto or his new railroad company would lose its charter from the state — again.

That man was Alfred Kelley, the man to whom Cleveland owes its status as a major city. Yet there is no statue or memorial to him anywhere in the city. As chief of the Ohio Canal Commission, he successfully argued that the state’s first canal should start at Cleveland, leading to the city’s explosive growth. But now he was a champion of railroads. His latest endeavor was the Cleveland, Columbus and Cincinnati (CC&C) Railroad which began its nascent engineering works on Scranton Peninsula in Cleveland’s Flats — whose tracks now belong to the Flats Industrial Railroad, but probably not for much longer.

In 1836, the state granted a charter to the CC&C which required that its construction had to begin within three years and be completed no later than 10 years after the start of construction. It failed to win enough private financing. The charter was revived in 1845 with the same conditions as before except the tracks were required only to link Cleveland and Columbus with a future extension to Cincinnati allowed.

Two years into the new charter, the company hadn’t built anything yet was in debt and faced another bleak outlook. That was, until the 58-year-old Kelley was enlisted as its new president. Kelley was already connected to two other railroads, banks in Ohio and on the East Coast, railroad suppliers in Great Britain and politicians everywhere in between. Kelley was also personally interested. As a state lawmaker, he moved to Columbus to avoid making the long 20-hour trips over the bumpy roads between Cleveland and the state capital, plied by the fastest, four-horse stagecoaches that hauled mail and passengers on this route since 1820.

Railroad construction finally starts

But Kelley still had to prove to the state by 1848 that construction on the CC&C was underway. So with several months remaining in 1847, Kelley and the board of directors filled up a wheelbarrow with dirt on Scranton Peninsula to commemorate the start of construction. To show that it wasn’t just a ceremonial event, the railroad company hired an old man to work five days a week to prepare the trackbed and to demonstrate to the state that construction was “ongoing.”

It worked. Not only was the charter continued, Kelley’s showmanship and subsequent speeches convinced financiers in Ohio and the East Coast to invest in the CC&C. His vision of the future was compelling. Railroads were the fastest form of land transportation ever invented and could carry huge volumes of freight and passenger traffic at low costs. In Ohio, rails would bring exponentially more opportunities. Kelley had arrived in the Ohio wilderness from Connecticut in 1810 at the age of 21 when Ohio’s population was just 230,760. By the end of the 1840s, it was nearly 10 times that. Kelley was a big reason why. The Ohio & Erie Canal, combined with the Erie Canal across New York state, had opened up Ohio’s agriculture and minerals to national and international markets more than two decades earlier. But Kelley saw the railroads were the future.

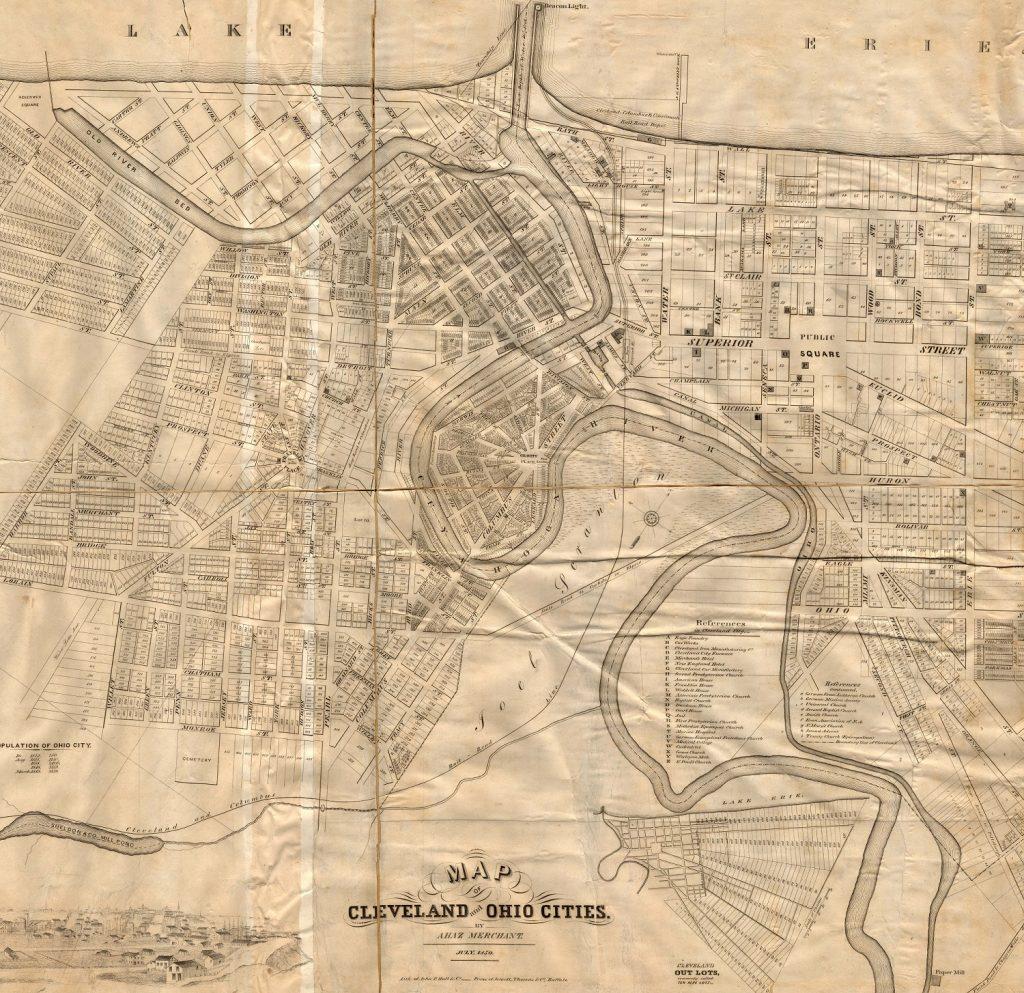

By 1849, up to 4,000 railroad construction workers were on the job while Kelley was out selling construction bonds in Ohio and in New York City. Three railroad bridges were built in Cleveland — an iron crossing of the new canal near its mouth, and two wooden trestles over the Cuyahoga River. That was quite a feat in an era when there were only two road bridges linking the municipalities of Cleveland and Ohio City. One rail bridge now connected Scranton Peninsula with the downtown side and the other connected the Scranton and Columbus peninsulas; descendant railroad bridges remain at those locations today. The latter bridge was needed to access a roundhouse for locomotives. It wasn’t built on Scranton Peninsula because much of the land was too swampy. Instead, CC&C bought and razed sections of Cleveland Centre, a densely developed mix of residences over shops surrounding a European-style market plaza on Columbus Peninsula.

Passenger stations were built at the mouth of the canal and at the lakefront to facilitate easy transfers between trains, canal packets and lake steamers. Also on the lakefront, a coal yard, dock, freight depot and warehouse were built, starting the industrialization of the city’s waterfronts. Tracks were laid across the dry, rising center of Scranton Peninsula to the southwest, through an industrialized Walworth Run to climb gradually out of the Cuyahoga Valley and head to Berea, then to Wellington 35 miles away. The first of several 18-ton locomotives were built for the CC&C by the Cuyahoga Steam Furnace Co. On November 1, 1849, that locomotive hauled a train of flat cars loaded with railroad construction materials. It was the first train to operate in Cleveland.

This image, extracted from the placard posted earlier, shows the Cleveland, Columbus & Cincinnati Railroad on Scranton Peninsula in Cleveland’s Flats circa 1850. This view looks northward with Columbus Road Bridge at left and downtown Cleveland above the train. The only building visible that’s still standing is the 1838-built St. John’s Episcopal Church seen at far left in Ohio City, then a separate municipality from the Forest City of Cleveland (WikiMedia Commons).

Cleveland’s first railroad begins

Regular passenger and freight services between Cleveland and Wellington began on May 16,1850 when the city’s population was a mere 17,034. The line to Columbus was completed on February 18, 1851 with regular services starting three days later. The line’s opening was commemorated by a special passenger train carrying more than 400 excursionists — Gov. Reuben Wood, the entire Ohio General Assembly, city councils of Cleveland, Columbus, Cincinnati and others. It left Columbus at 8 a.m. When the train came at dusk down Walworth Run, across Scranton Peninsula and over the Cuyahoga River to Lake Erie, it announced its arrival in Cleveland with three whistles. A friendly three-cannon salute was returned. The train had covered the 135 miles entirely within a single daytime — twice as fast as the fastest stagecoaches.

The next morning, “three companies of Cleveland militia and the entire city fire department paraded in front of the excursionists, who were seated on a grandstand erected on Cleveland’s Public Square,” according to this historical summary. It was noted that, although Kelley was introduced, he did not speak to the assembled masses. Later, the excursionists boarded a train to Hudson, on the portion of the Cleveland, Warren & Pittsburgh Railroad (later Cleveland & Pittsburgh) that was completed. It would reach the Ohio River at Wellsville the next year.

Also in 1852, the Cleveland, Painesville and Ashtabula Railroad was constructed, followed by the Cleveland and Toledo Railroad in 1853, Cleveland & Mahoning Railroad in 1856, Rocky River Railroad in 1869, Wheeling & Lake Erie in 1877, Valley Railway in 1880, and the Cleveland and Southwestern Railway in 1888. All were eventually consolidated into larger railway systems linking the Midwest and Northeast. Railroads were standardized to the same gauge (distance between rails) in the 1880s to improve connectivity. The trains got bigger, faster, safer and more efficient. By 1880, Cleveland’s population had grown nearly tenfold in just 30 years to 160,146.

From the 1820s to the 1920s, thanks to innovation and investment, the rail travel time between Cleveland and Columbus had shrunk from 20 hours to under three with similar, proportional reductions to other rail-served communities. Shipping costs were shaved and industries flourished, especially in Gilded Age Cleveland due to its proximity to sources of coal, iron ore and other raw materials. Kelley saw the nascent industrial progress but missed out on Cleveland’s explosive growth after the Civil War. He died in 1859 at the age of 70. Still, he saw Cleveland grow from a few hundred residents to about 40,000.

Cleveland’s productive peninsulas in the Flats

On the swampy Scranton Peninsula where Cleveland’s first railroad saw construction, the rail access attracted industrial development. Two of the biggest industries stayed active here until the late-20th century. One was the Upson Nut Co. which expanded from Connecticut and was acquired in 1930 by Cleveland-based Republic Steel, once the nation’s third-largest steelmaker. Republic’s Upson Bolt & Nut Division employed nearly 2,000 workers, confined mostly to the west of the CC&C tracks.

Another large industry was Northern Ohio Lumber & Timber. From 1864-2002, it leased land from Scranton-Averell Inc. and its predecessors, near where Scranton Road met Carter Road. As the oldest lumber company and sawmill in Ohio and the fifth-oldest lumber company in the USA, it continues in business at 2850 W. 3rd St. Yet another successful industry on the peninsula was the railroad wheel-maker Cleveland Wheel & Foundry Works, started in 1860 by Thomas Maher, one of Cleveland’s most successful early Irish industrialists. He employed 250 laborers.

Railroad business also was successful. By the 20th century, the CC&C had been merged into other companies, becoming the Cleveland, Cincinnati, Chicago and St. Louis Railway, or Big Four Route. In 1906, it was acquired by the New York Central, one of the nation’s largest, busiest and most prosperous railroads, yet the Big Four continued its own identity for several more decades. It operated roughly 60 trains per day to and from Cleveland, with some operating through to the East Coast on the New York Central, either through the Flats or via the new Belt Line built in 1910-12 around the south and east sides of the congested city. To serve Flats industries, the Big Four built DK Yard on Scranton Peninsula and moved its locomotive roundhouse from Columbus Peninsula to Linndale where a larger Big Four rail yard was constructed.

But railroad operations on Columbus Road Peninsula continued. The Big Four served the Portland Cement Co. and the Cleveland Milling Co. The latter was a flour mill at Merwin and German streets, an industrial concern that operated a mill going back to 1856. This grain mill was expanded over the decades, adding a seven-story brick building in 1882 according to a National Register of Historic Places filing. A group of concrete grain elevators were built in 1937, some equaling the height of a 15-story-tall building and held flour delivered by trains and trucks for transfer to ships worldwide.

Smokey Scranton Peninsula in about 1937 with the Northern Ohio Lumber yards in the foreground, New York Central’s Big Four Route cut across the river two years before the Carter Road lift bridge would be built next to it. Beyond the railroad is Republic Steel’s Upson Bolt & Nut Division which was idled by a strike that year. The long elevated bridge to the right is the Cleveland Union Terminal Railroad that diverted New York Central passenger trains out of the labyrinth of Flats rail traffic (ClevelandMemory).

Cleveland industries, railroads decline

The Upson Bolt & Nut Division was the first steel mill in the Flats to close. It, like much of the steel industry that faded into the 1970s, was saddled with outdated facilities, foreign competition, environmental regulations and chronic labor-management problems. Federal Wire & Steel acquired the aging plant in 1973 but halted operations, preferring instead to sell it off piece by piece for reuse or scrap. By the 1990s, most of the steel plant had been demolished and the property sold to real estate developer Forest City Enterprises.

Goliath railroad New York Central merged in 1968 with the only Midwest-Northeast competitor larger than it, the Pennsylvania Railroad, to create the Penn-Central Transportation Co. The result in 1970 was the biggest corporate bankruptcy in American history. It and five other Northeast railroads were combined by the federal government in 1976 to create Conrail which proceeded to rapidly abandon redundant railroad lines after the rail industry was deregulated in 1980. One of those was the 5-mile Clark Branch — the former Big Four mainline, from the lakefront, through the Flats and up Walworth Run to a location called Knob where it met a track coming up the the Big Creek valley from the steel mills.

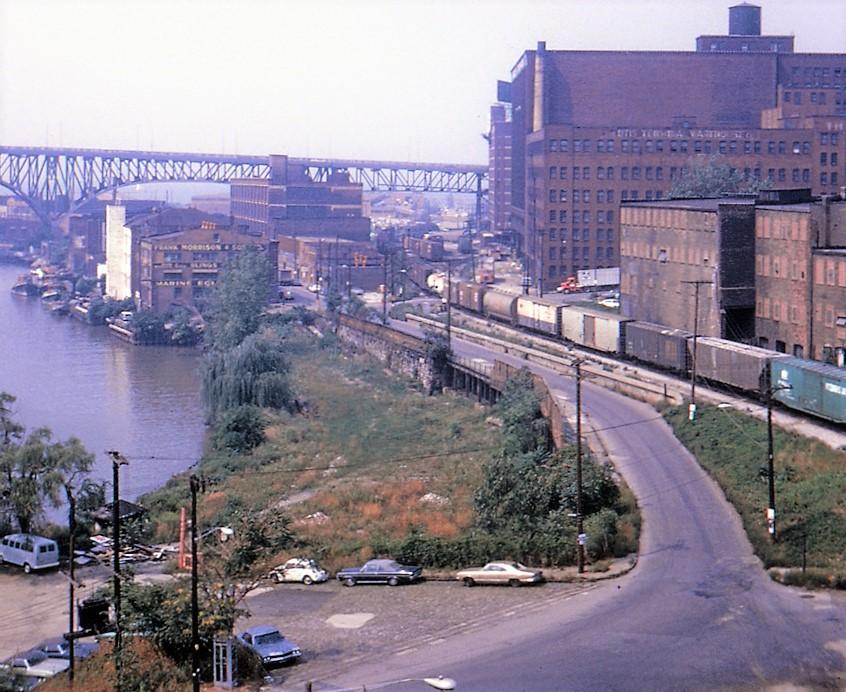

On Aug. 28, 1970, a Penn-Central freight train traveling between Columbus, OH and Selkirk, NY near Albany passed Settlers Landing on Cleveland’s first railroad. This north view from the Detroit-Superior Bridge shows Cleveland’s Flats was a grimy place after decades of industrial pollution (twinplanets.com).

Transitioning to new owners and uses

Conrail continued to serve local shippers along the Clark Branch but all through freight traffic was diverted to parallel lines while putting the property up for sale. The first buyer — the city of Cleveland — stepped forward in 1983 to acquire 1 mile of right of way south from Conrail’s Chicago-East Coast mainline along the lakefront to and including the railroad’s lift bridge over the Cuyahoga River, next to Carter Road. Conrail was happy to get rid of it, selling it for $1. The tracks were pulled up and replaced with new city streets — West 10th Street north of St. Clair Avenue and Old River Road south of it. In 1994-96, the Greater Cleveland Regional Transit Authority’s light-rail Waterfront Line was constructed alongside those new city streets.

The same year the Waterfront Line opened, shipping investor Arthur Fournier Jr. of South Portland, ME bought the surviving 4 miles of Conrail’s Clark Branch as Flats Industrial Inc., a Delaware corporation doing business as Flats Industrial Railroad Company. The Class III short-line railroad used private and public dollars to fix up the tracks, construct a four-track rail yard and sand transload facility on Scranton Peninsula. It later added a three-track interchange yard in the vicinity of Fulton Road to transfer rail cars between the large Class I railroads and Flats Industrial Railroad shippers. Those shippers were the sand transload, the Flats flour mill owned by Cereal Food Processors Inc. and a manufacturer of industrial organic chemicals named Werner G. Smith Inc., 1730 Train Ave.

Before June 1, 1999, the Class I railroad with whom Flats Industrial interchanged business was Conrail. Afterwards, it was Norfolk Southern (NS) which jointly acquired Conrail with CSX Transportation Inc. and split up Conrail’s routes roughly evenly between them. NS wanted the Clark Branch south of where its Cleveland District tracks crossed it, at a place near Monroe Cemetery with an old-time railroad name — Cloggsville. There it built a double-tracked connection so it could detour most of the freight traffic from the Cleveland District, out of West Shore suburbs like Lakewood and Bay Village. NS acquired two miles of right of way from Flats Industrial so it could add the second main track.

The same area as in the previous photo, albeit from a higher angle, in the 21st century shows the changes in Cleveland from an industrial giant to a city of health care, educational institutions, services, advanced manufacturing and heritage tourism. Gone are the railroads and factories, replaced by parks, light-rail transit, trails, apartments, restaurants and entertainment venues (DestinationCleveland).

The end of the line

Flats Industrial Railroad founder Fournier passed away in 2013. Three years later, ownership of the railroad in the form of stock went to his widow and four children. One of his children won a lawsuit in a Maine court in 2018 to affirm his standing in determining the value of his ownership interest in the railroad. Apparently the family members were more interested in selling the railroad than running it. By then, the flour mill was the railroad’s lone customer. The mill’s ownership had transferred in 2014 to Grain Craft which reportedly was informed by Flats Industrial that it would no longer serve the flour mill after July 2020, thus forcing the mill’s closure, according to a source close to the railroad.

Specifically, Grain Craft blamed the closure on “challenging market dynamics and long-term supply chain obstacles,” according to an April 2020 World Grain article. Prior to announcing the mill’s closure, Grain Craft reached out to the Ohio Rail Development Commission for assistance in keeping the railroad operational, according to a commission staffperson who spoke on the condition of anonymity. It was Grain Craft’s last mill located east of the Mississippi River and the last grain mill of any kind left on the Cuyahoga River.

On October 11 of this year, Flats Industrial filed with the federal Surface Transportation Board (STB) a request to abandon rail freight service on the 1.85 miles of right of way it owns. Since railroads are a public service industry similar to a utility, they operate under state or federal certificates of convenience and necessity. Thus a railroad is legally obligated to provide service if a customer requests it. A railroad cannot legally withdraw service on its own. The railroad and its legal representative Baker & Miller of Washington DC claimed in their filing with the STB that it was the mill’s closure two years ago that prompted the abandonment.

“No formal complaint has been filed by a user of rail service on the Line or a state or local government entity acting on behalf of such user regarding cessation of service over the Line is either pending before the Surface Transportation Board or any U.S. District Court or has been decided in favor of the complainant within the two-year period,” wrote Flats Industrial attorney Crystal Zorbaugh.

Site preparation has begun to realize this post-industrial vision for Scranton Peninsula, with the right of way of the Flats Industrial Railroad converted to an all-purpose trail, curving from lower right to crossing the Cuyahoga River at left. While post-industrial here means a mix of residential and services, it doesn’t eliminate industrial entirely. At the bottom is the planned new production facility for the Great Lakes Brewing Company (CPC).

From rails to trails

While the Flats Industrial Railroad didn’t survive Fournier’s passing by a decade, his family is likely to get paid by the sale of the property that belonged to the once prominent CC&C railroad. For the swampland on Scranton Peninsula soon gave way to job-rich but polluting industries. And those are now giving way to luxury apartments and brewpubs served by all-purpose trails along other former rail lines. One of those is the Cleveland Foundation Centennial Lake Link Trail on the former Cleveland & Mahoning. Zorbaugh wrote that Flats Industrial is likely to meet a similar fate.

“FIR (Flats Industrial Railroad) believes that the proposed abandonment is consistent with, and would promote, existing land use plans,” she said in the abandonment application. “The land adjoining the (rail) line consists of a combination of urban commercial and residential areas.”

“We are actively working with Flats Industrial Railroad to get that land under control and working with property owners to maximize access to the river,” said Jim Haviland, executive director of Flats Forward, a community development corporation, in December 2021.

“We want to bring connectivity to Scranton Peninsula,” said Seth Mendelsohn, founder and principal of Shaker Heights-based Silver Hills Development that is developing a riverside apartment complex. “We’re especially excited about the breweries that are going in and the parks that are going in.”

Silverhills, in partnership with Edwards Communities of Columbus, has started site preparation for building 300 apartments where Upson’s ore transfer facility stood. Similarly, NRP Group plans 300 apartments on the former sites of the Cleveland Wheel & Foundry Works and Upson’s open-hearth furnaces. Scotland-based Cleveland BrewDog turned a long-vacant, century-old Cuyahoga Lumber Co. sawmill into a new brewpub. And where Upson’s forge shop stood, crews are leveling the land for Great Lakes Brewing Company’s relocated production facilities that might benefit from rail access. Company officials didn’t respond to NEOtrans inquiries.

While a recreational trail on the former CC&C railbed will certainly benefit Scranton Peninsula’s new economic destiny, there appears to be no public awareness of the importance of this site in Cleveland’s history let alone whether to acknowledge it. This is a site where Alfred Kelley and other builders of Cleveland’s Gilded Age greatness got started in laying the groundwork for the first rails that would feed it. Perhaps his accomplishments might still be remembered and memorialized here someday.

END