An outbound Waterfront Line train passes recent developments at Flats East Bank on Labor Day weekend in 2018. More transit-supportive development is needed along the Waterfront Line, especially affordable housing and commercial tenants like grocers, basic clothing stores and health care providers (KJP). CLICK IMAGES TO ENLARGE THEM.

16 grad students offer report, suggestions

When a group of 16 urban planning graduate students from Cleveland State University (CSU) took a critical look at the Greater Cleveland Regional Transit Authority’s (GCRTA) light-rail Waterfront Line, they unsurprisingly found a number of things lacking. But there were some surprises discovered during their research that could boost ridership if addressed effectively.

They shared their findings in a presentation earlier this week at CSU’s Dively Auditorium to a group of about 60 people, including those from the city and GCRTA. The team of students also will post a Web site on the project and issue a report due to be released soon. It was all a part of CSU’s Masters of Urban Planning and Development (MUPD) routine capstone project to demonstrate a student’s mastery in their field of study.

Capstone work usually results in a project that combines and applies the student’s knowledge and skills acquired throughout the course of a degree program. Overseeing the project were two instructors at CSU’s Levin College of Public Affairs and Education, Tom Hilde and Jim Kastelic. This project comes at a time when the city is trying to improve linkages between Downtown Cleveland and its two waterfronts with its Shore-to-Core-to-Shore tax-increment financing district. The Waterfront Line does that, albeit mired in neglect.

The CSU MUPD planning team, led by Hilde and Kastelic, included Connor Brentar, Alahjanai Carlisle, Taviana Carr, Christine Fergus, Elizabeth Kravanya, Nate Lull, EJ McGorty, John Miesle, Sam Munro, Jody Olbrecht, Alex Ordodi, Kelsey Phillips, Hanna Sauberan, Celina Sotka, Krystal Sierra, and Mae Thompson.

This MUPD capstone project was so ambitious that it had to be broken up into three zones along the Waterfront Line — the riverfront, the North Coast Harbor area and the area near the Municipal Parking Lot. The latter zone also included consideration of a stated need to extend the Waterfront Line beyond downtown’s 15-minute walkshed, either east to the CHEERS lakefront development area or as a downtown loop which GCRTA found feasible more than two decades ago.

The 2.2-mile, $70 million Waterfront Line was built in 1996 as a bicentennial legacy project to celebrate the city’s 200th birthday. It operated as an extension of the Shaker Heights-Tower City Center Blue and Green lines to improve access to a traffic-congested Flats East Bank District and serve attractions at the then-new North Coast Harbor at the foot of East 9th Street.

Ridership actually exceeded projections of 600,000 boardings in its first year and held near 1 million riders per year in the late 1990s. But when fares were increased and the Flats East Bank started to fade at the turn of the century, use of the Waterfront Line fell. Ridership briefly recovered a bit to near 500,000 annual boardings until the Great Recession of 2008-10 hit. GCRTA cut back Waterfront Line service to weekends only, pared other routes and raised fares systemwide.

The line didn’t run at all from 2021-23 as a 645-foot-long bridge over Front Street and the lakefront railroad tracks was rebuilt for $8.7 million. Five stations were also spruced up last year for $1 million total to prepare for the Waterfront Line’s return. So far it has operated only during Cleveland Browns home games and the solar eclipse last month.

That was the MUPD students’ first suggestion to improve the Waterfront Line — to operate it daily again, although there was some debate among the students on how late at night trains should run. Some suggested it should run 24 hours a day so Flats bar patrons and workers can return home, people can connect to/from Amtrak trains, and early-morning commuters and airport-bound business travelers can ride.

A summary of proposed developments along the Waterfront Line. It includes a mix of greenspace, high-rises and single-family homes built on the Municipal Parking Lots, a multimodal transportation center, development of The Pit parking lot west of West 3rd Street, a bio-solar park inside the loop near the Cleveland port, and developing Flats parking lots to create more of a neighborhood there (KJP).

One of the team’s biggest surprises was that the rail line and the land use around it doesn’t serve GCRTA’s most common rider — an African-American woman earning less than $25,000 per year and probably doesn’t have a car. Instead, the most common person living and working along the rail line is a young professional white male who has a car. It doesn’t mean they aren’t interested. Two-thirds of those responding to CSU’s Waterfront Line survey earned more than $60,000 per year.

So the CSU team, operating as if it were a consultancy called 17th Street Studios and working for a client — the Cleveland Planning Commission, looked for development opportunities. A barrier they encountered was that profitable, private parking lots abound along the Waterfront Line. The students suggested city incentives such as a grants, tax credits and supportive zoning to encourage property owners to part with their parking lots.

Surprisingly, the students found that one of the biggest owners of parking lots and other land along the rail line is the city itself. So the team suggested the city consolidate parking lots into garages at strategic locations. That could free up land for dense developments to attract residents and visitors that would be more likely to ride transit. That would likely involve building workforce housing, health care services, grocers and other basic-needs retail, the team noted.

The MUPD students also weighed in on the fate of Cleveland Browns Stadium, saying it would be better for the Waterfront Line if the Browns stayed put rather than move to a domed stadium in Brook Park and demolish the existing stadium for an expansion of the city’s recreation-heavy lakefront vision.

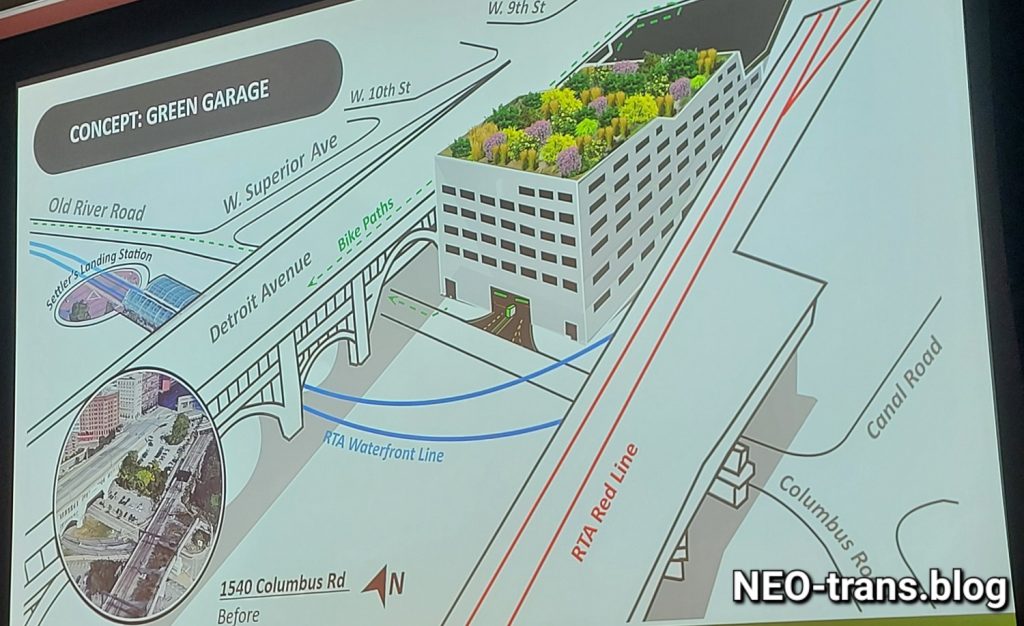

A city-funded and owned parking garage with a green roof is proposed between the Red Line tracks and the Detroit-Superior Bridge. It could also include an internal ramp for bikes to rise/descend to/from the bridge’s street level to the subway deck, proposed to be redeveloped as the Low Line, and from/to Columbus Road and the Waterfront Line’s Settlers Landing station (KJP).

Conversely, the students said having the Shoreway remain as a highway makes it difficult to reconnect and redevelop the lakefront for people instead of cars. They supported its proposed conversion to a boulevard as well as the city’s plans for a North Coast Connector land bridge over the Shoreway and lakefront railroad tracks.

Some low-cost, high-impact changes include fixing up public spaces like Settlers Landing with picnic tables, a splash pad, kayak/paddle boat launch and community-oriented programming like festivals and open-air markets. Planned new trails and redesigning East 9th and West 3rd streets as complete streets so pedestrians and cyclists are safe from cars could also help increase utilization of the Waterfront Line, they said.

But one of the MUPD students’ biggest surprises was the consistency of ideas and suggestions they got from stakeholders. Each suggested making stations the focal points of their surroundings that offered more walkable infill development, particularly with more affordable housing and basic services.

The conclusion was that the solutions to boosting ridership on the Waterfront Line seem widely shared but have yet to be acted upon. Kastelic said that if anything comes out of this project, it is to foster a community will to act. But while city officials at the meeting expressed interest in having the students give a presentation to an upcoming Planning Commission meeting, GCRTA officials weren’t so enthusiastic on a similar presentation for an agency board meeting.

END