CSU work to support city’s lakefront planning

Over the next two months, a Cleveland State University study will identify untapped lands in Downtown Cleveland along the inactive light-rail Waterfront Line and consider how to encourage their development for the benefit of the lakefront and the transit line. The findings could ultimately be incorporated into the city’s lakefront plan which has yet to be finalized.

The planning work by Cleveland State University’s (CSU) Master of Urban Planning and Development (MUPD) students is for its routine capstone project to demonstrate a student’s mastery of a field of study. Capstone work usually results in a project that combines and applies the student’s knowledge and skills acquired throughout the course of a degree program.

In this case, two instructors at CSU’s Levin College of Public Affairs and Education, Tom Hilde and Jim Kastelic, reached out to the City Planning Commission (CPC) for capstone project ideas, as they typically do each winter. Given all of the recent news and efforts surrounding the lakefront, that was the topic tent where the instructors went looking for suggestions.

“The CSU professors were interested in a topic related to our lakefront,” Cleveland Planning Director Joyce Pan Huang told NEOtrans, “With CPC’s recent work around TOD (transit oriented development) and Shore to Core to Shore, we thought that the Waterfront Line might be a topic that would hit all of the planning department’s teaching goals.”

The Greater Cleveland Regional Transit Authority (GCRTA) is also supportive of the CSU project to look at ways of promoting TOD near stations on the 2.2-mile Waterfront Line. Built in 1996 for $70 million as a Cleveland Bicentennial Legacy Project to help celebrate the city’s 200th birthday, the rail line has been largely inactive since before the pandemic started in 2020.

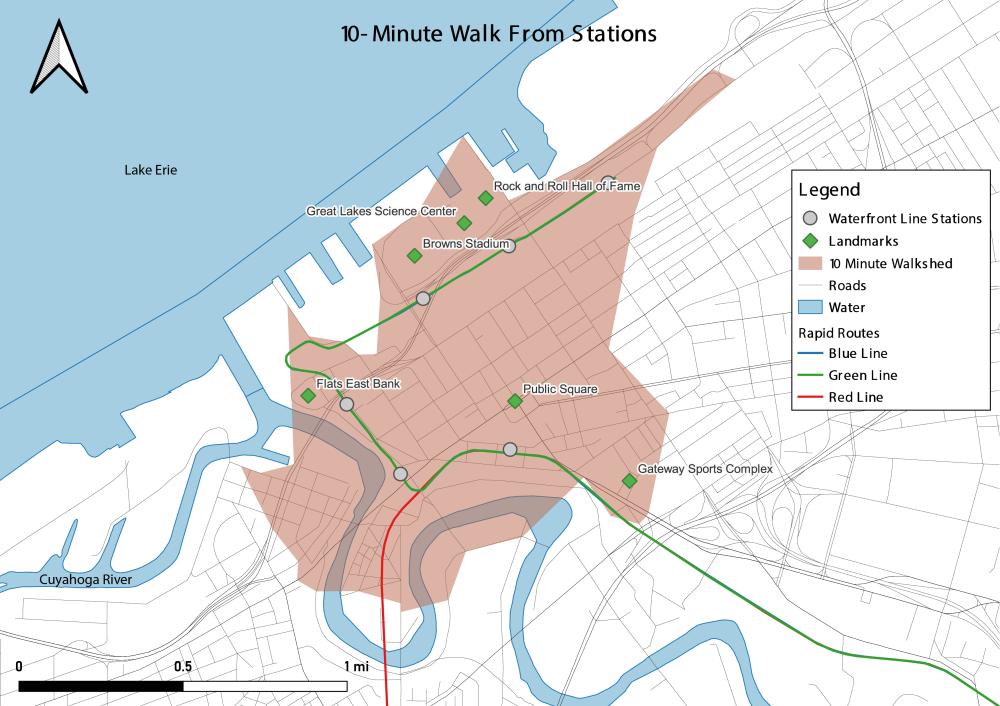

This map of Downtown Cleveland shows areas that are within a 10-minute walk of a Waterfront Line station. While much of downtown is accessible in 10 minutes, most intra-downtown trips can be walked in 10 minutes or less without using the train. There are far fewer destinations offering basic necessities with 500 feet of a station (CSU).

Its closure after the pandemic was due to a 645-foot-long bridge over Front Street and the lakefront railroad tracks needing $8.7 million worth of repairs. Five stations were also spruced up last year for $1 million total.

Work on the bridge and stations was done in time so the line could serve nine Cleveland Browns regular season home games in 2023. But it has not operated since and GCRTA has not stated when it would restart regular daily service on the line. The earliest that could happen is later this spring or perhaps this summer.

More history of the line’s early years is provided later in this article, but despite ridership exceeding projections early on, the light-rail extension of the Shaker Heights-Tower City Blue/Green lines has lumbered on ever since without a clear purpose or vision. It has received little more than a passing mention in the city’s current lakefront plans.

“With all of the current waterfront planning (efforts) that are underway, it just made sense to see if the students could come up with some ideas on how best to maximize this $70 million investment,” said CSU Research Fellow Jim Kastelic, formerly a deputy director at the Cuyahoga County Planning Commission. “We also felt that linking public transportation with so many trail projects in the Flats and lakefront is important to their success.”

While CPC and GCRTA did not hire CSU to conduct a planning study, the CSU professors and students are acting as if they were. They are treating CPC and GCRTA as clients and are due to present their findings to them and the public in May, said MUPD graduate students John Miesle and Sam Munro.

One of the many untapped potentials of the light-rail Waterfront Line is the never-built station at the Port of Cleveland where an aquarium was planned to be built, then a World Trade Center, then a Defense Finance Accounting Service center and then the new headquarters of the Eaton Corp. Thirty years later, the nearly 3 acres of port authority-owned land inside the Waterfront Line ramp remains undeveloped (Google).

“Although it’s an academic exercise, we’re trying not to think of it that way,” Miesle said. “We’re trying to treat it like we’re working on a real project for a real client with real deliverables. It helps that the CPC has taken an interest in it. It’s not lost on us that light rail is an incredible asset. It’s a tragedy that this light-rail line is sitting under-utilized. If we could play a part in reactivating it, we’d be honored to do that.”

The capstone project will conduct research on TOD including financing and development options and CPC will share some of its work on station planning that the city is exploring along other parts of the transit network and what other Midwest cities are doing with their rail transit lines. The input phase is already underway and involves interviews of stakeholders and an online public survey that will continue until late April, Miesle said.

The students will assess the existing landscape and conditions of the Waterfront Line project area, such as the land use, zoning and development status near rail stations. Part of the work will include a Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities and Threats (SWOT) analysis and look at internal and external factors that will affect the current landscape and future impacts of the project.

Additionally, the students will prepare an analysis of how the Waterfront Line can be integrated into the Shoreway’s revision plans, which Kastelic says will be available during the research phase of the project. The current status of downtown connectivity planning, with consideration of routes to/from the stations, and current off-road trail planning initiatives within a quarter-mile to half-mile walkshed of the Waterfront Line will be considered.

And lastly, the students will identify opportunities for development/re-development of properties along the Waterfront Line, including options for mixed use, affordable housing, greenspace and public art. They will present those findings in a business and marketing plan to address issues of sustainability and fiscal integrity for the proposed recommendations, as well as timelines, funding options and implementation strategies.

“This is a very exciting time for Cleveland, and playing a part in the waterfront redevelopment is an honor,” Munro said.

The South Harbor Waterfront Line station, outlined in red, is in a dead-zone for more than 97 percent of the year when the Cleveland Browns aren’t playing home games. Cleveland’s lakefront planning has proposed building transit-oriented development on most of these underutilized, city-owned parking lots (Google).

The Waterfront Line was originally envisioned in the 1980s as the Flats Trolley — a special-events-only, single-track, heritage-style streetcar linking GCRTA’s Tower City rail and bus hub with the fast-growing and highly congested Flats East Bank entertainment district. Costing just $10 million, the Flats Trolley was proposed to run on the south side of the lakefront railroads to East 9th Street to serve Cleveland Municipal Stadium and the newly built North Coast Harbor.

But Mayor Mike White and then-GCRTA General Manager Ron Tober wanted to extend the Blue and Green Lines as a full-blown, double-tracked, light-rail line, recalls Mark Carlson of Bay Village who was then president of the rail and transit advocacy group All Aboard Ohio.

The rail line was funded as a Bicentennial Legacy Project, along with Settlers Landing Park, the Great Lakes Science Center, Cuyahoga River bridge lightings and more to celebrate the city’s 200th birthday on July 22, 1996. It was a ridership success in its first few years. Estimated to carry 600,000 riders per year, it hauled nearly double that in 1997, thanks to fares discounted 50 percent for Waterfront-only travel.

The new National Terminals Apartments, today’s Archer Apartment Homes, added a retail presence and entrance facing the new Flats East station. Carlson said other real estate projects moved forward, such as the Bridgeview Apartments, with their developers citing the Waterfront Line as part of their interest.

Deals were worked out with Flats businesses so that customers who showed active GCRTA fare media, like a current day pass, could get a discount on their drinks, a meal, or a ride on the Holy Moses Water Taxi. Carlson said he often saw downtown workers using the Waterfront Line to have lunch in the Flats.

A draft version of the city’s lakefront plan shows several potential traffic generators for the Waterfront Line. It also proposes to replace the East 9th and West 3rd stations with a single station in a multimodal transportation hub shared with transit buses, Amtrak trains, and the North Coast Connector landbridge (FO).

GCRTA wanted to build on the Waterfront Line’s early success by extending it beyond the Municipal Park Lot. A two-year study completed in 2000 recommended building Waterfront Phase II for $118 million as a downtown loop on East 17th Street, Euclid Avenue, East 21st/22nd streets, Community College Avenue and East 30th Street back to the Red/Blue/Green lines.

It would add up to 800,000 riders per year, mostly from CSU students, the study showed. But shortly after arriving GCRTA in 2000, then-General Manager Joe Calabrese halted all of the agency’s planned rail expansions. By 2000, the rail line’s peak years were already behind it. That was despite the Cleveland Browns returning in 1999 with its own Waterfront Line station built next to the new football stadium.

“Waterfront trains ran until 2:30 in the morning on weekends to give the bar crowd a safe ride home,” Carlson recalled. “It was a useful service for many people back then. But when the Flats started going downhill in the early 2000s, so did the Waterfront Line. Then we had all of the RTA fare increases and service cutbacks in the late 2000s and the Waterfront Line was an easy target. It never recovered.”

Resuscitating the Waterfront Line at a time of a declining post-pandemic office market will be a challenge, but not an impossibility. Multiple GCRTA rail stations are seeing residential-heavy, mixed-use TOD investment activity — Ohio City, Little Italy, Van Aken District, Buckeye-Woodhill, West Boulevard, West Park, and Superior.

In fact, GCRTA data shows rail stations that have suffered the least since the pandemic are those with smaller or no park-n-ride lots, where the train is used more than just for commuting to and from work. Stations that are used to access the basic necessities of life — work, school, healthcare, shopping, social activities — have maintained steady ridership.

END