CSX Transportation Inc. pulled up its railroad tracks into Downtown Cleveland north of the Lorain-Carnegie Hope Memorial Bridge, which is where this view was captured on May 29. However, south of the bridge, the tracks were still in place as of yesterday. At left is the new Cleveland Clinic Global Peak Performance Center including a practice facility for the Cleveland Cavaliers (Mark Schwinn). CLICK IMAGES TO ENLARGE THEM.

CSX removes tracks at Bedrock’s riverfront site

On March 16, family, friends and colleagues of Thomas V. Chema received horrible news. The 78-year-old leader of civic causes and institutions died suddenly at his home in Downtown Cleveland. Chema was in the midst of excitedly pursuing his latest civic endeavor — the extension of Cuyahoga Valley Scenic Railroad trains into downtown.

Aside from the loss of a loved one and friend, Chema’s passing put a significant dent into the momentum of this new calling. Those who knew Chema remembered him as a true gentleman who cared about his community. He stepped up to lead the Public Utilities Commission of Ohio, Hiram College, the construction of the Gateway baseball and basketball stadiums in the early 1990s, and aiding various nonprofit associations.

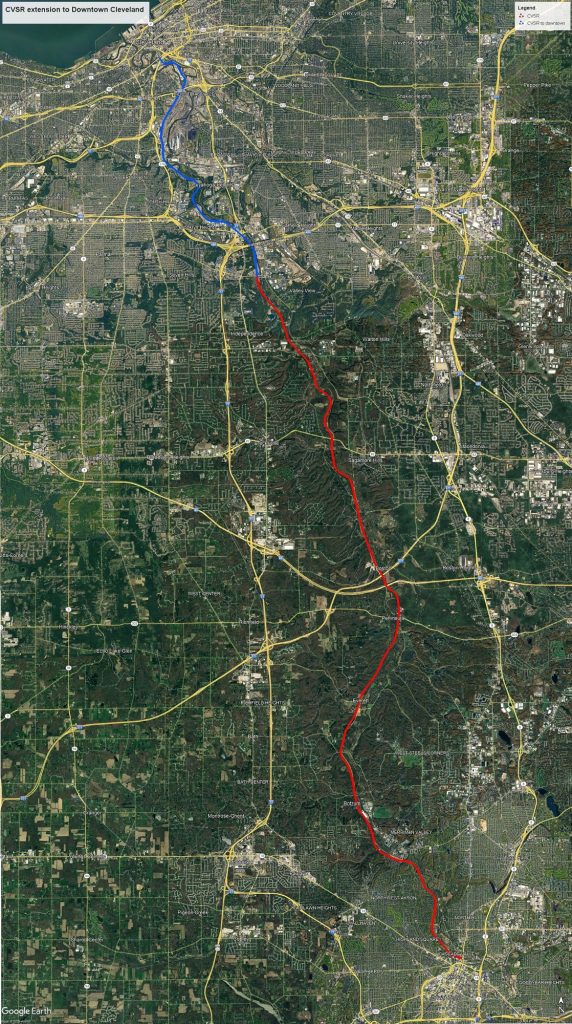

Chema was looking forward to following up on a study commissioned by the Northeast Ohio Areawide Coordinating Agency (NOACA), released this past winter. Conducted by global engineering giant AECOM, it attempted to determine what’s needed to extend CVSR trains from suburban Independence to Downtown Cleveland.

“Losing Tom hurt in a lot of ways, and the CVSR extension was one of them,” said NOACA Executive Director Grace Gallucci to NEOtrans. “We lost momentum when we lost Tom.”

But that doesn’t mean that the CVSR downtown extension was lost. Instead, Gallucci said NOACA will continue to be a convener of public and private partners in the project. Meetings continue to be held, and more are being organized by the five-county metropolitan planning organization.

The biggest barrier in the path of CVSR trains is the owner of most of the tracks that the scenic railroad’s trains would use. During the study, what little contact local planners had with track-owner CSX Transportation Inc. wasn’t helpful. The goliath Fortune 500 company that earned $14.5 billion last year “gold-plated” its demands for accessing a seldom-used rail right of way.

CSX told AECOM planners that totally new tracks and costly new satellite-based traffic control system over the nine-mile extension of passenger rail service would be needed, costing nearly $200 million. At the same time, CSX denied the planners entry to their right of way, complicating their fact-finding efforts.

Despite CSX’s apparent obstructionism of a community-led public improvement, it has taken CVSR’s new President Larry Stevenson, a railroader, to speak their language and get them to keep talking and hopefully find some common ground.

Stevenson was hired by CVSR’s board in September 2024 to succeed Joe Mazur, who retired after seven years of service to the nonprofit railroad that operates on 26 miles of track owned by the National Park Service. Downtown Akron is the railroad’s southern terminus.

Previously, Stevenson was CEO of the Island Corridor Foundation, a nonprofit organization in Vancouver, Canada. In that role, Stevenson was responsible for the strategy, planning and day-to-day management of a 180-mile rail corridor. His leadership was instrumental in revitalizing the organization and securing its relevance and standing with stakeholders, the public and government entities.

If that sounds like what he’s been asked to do in extending CVSR services north to Downtown Cleveland, you’re probably thinking what the CVSR board of directors was reportedly thinking when they hired Stevenson.

“We have had some initial discussion with CSX regarding the project to extend service into Cleveland,” Stevenson told NEOtrans. “We have discussed our plans and how those plans could potentially fit into current CSX operations. CSX has raised concerns regarding any potential impact on their operations and any liability that could be associated with operation of passenger service on CSX trackage.”

While he said he would hesitate to characterize the CVSR-CSX conversations as “negotiations” he said he plans to continue the dialogue with CSX about the Cleveland extension project, its opportunities and its challenges.

“There is still a lot work to do,” Stevenson added.

If CSX’s demand for a satellite-based Positive Train Control system was removed and existing track was rebuilt to federal passenger rail standards, it could cut the downtown extension’s start-up cost by about 65 percent to about $68 million. NOACA’s long-range plan has an even lower start-up estimate — $40 million. CVSR trains travel at 25 mph on National Park Service-owned track through the park.

Track north of CVSR’s northern terminus at Rockside Road station in Independence has different ownerships. South of Ohio Route 21 in Valley View to Rockside, 1.5 miles of track is owned by the National Park Service. North of Interstate 490 to downtown, 1.4 miles is owned by Bedrock Real Estate to which CSX has an easement. About 6 miles of track in between is owned by CSX.

CVSR and the study team urged CSX to donate or sell its right of way and easements, including a narrow strip for a CVSR-only track next to CSX’s Clark Yard near Steelyard Commons. South of the yard to where the National Park Service-owned track begins near the Route 21 overpass, CSX uses the line only about two times per week to serve lumber and cement customers.

Nationwide, such light-density freight lines have been leased to short-line railroads to service. And where the freight service isn’t time-sensitive, it has been shifted to the overnight hours on tracks shared with daytime passenger trains. Thus it is possible that, during daytime hours, CVSR could operate entirely on passenger-only tracks over the full nine-mile extension to downtown.

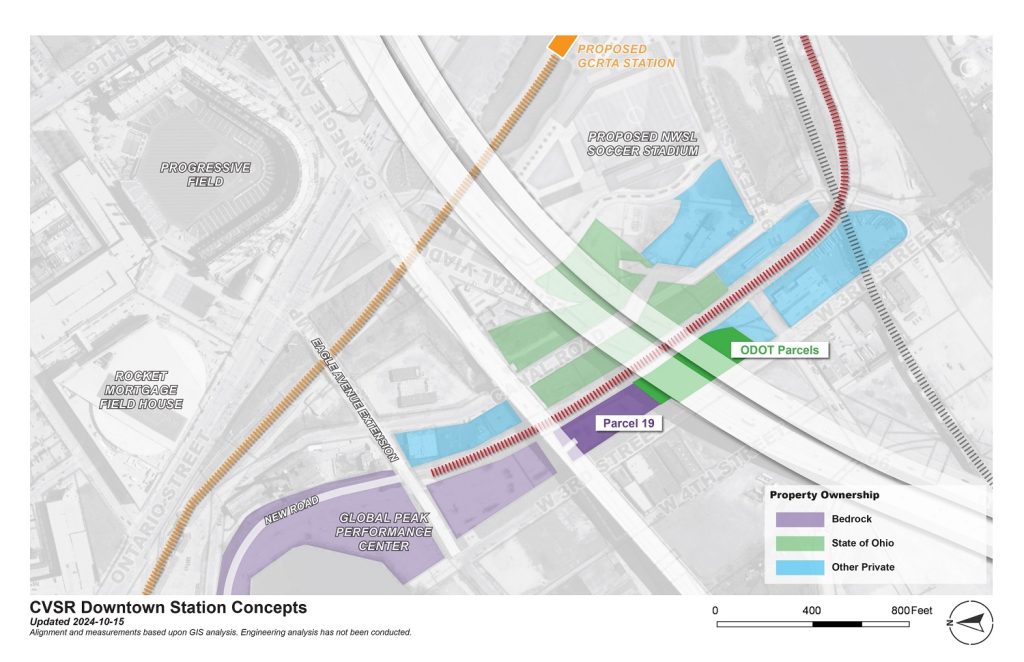

Bedrock has proposed a downtown CVSR station south of its Riverview development, below Interstate 90’s Inner Belt bridge. CVSR and NOACA’s planning team hoped to secure a station closer to the action downtown where a comfortable pedestrian link could be had with the Greater Cleveland Regional Transit Authority’s rapid transit system.

Instead, the railroad tracks were removed in recent weeks north of the Lorain-Carnegie Hope Memorial Bridge to just downhill of Tower City Center where a steam heating plant is to be razed by Bedrock Real Estate. That includes the section next to the under-construction Cleveland Clinic Global Peak Performance Center with a practice facility for the Cleveland Cavaliers basketball team.

“As a railroader it is always hard to watch tracks being removed as it serves to place limitations on the future,” Stevenson said. “We were certainly aware the tracks would come up as part of the Bedrock project and it was considered as part of our project.”

“Bedrock did not remove the railroad tracks,” said Lora Brand, vice president of communications at Bedrock.

CSX’s Director of Medial Relations Austin Staton didn’t respond to an e-mail sent three days ago seeking comment for this article. CSX is headquartered in Jacksonville, FL.

While large Class 1 railroads like CSX aren’t in love with having passenger service on their tracks, most work out positive, productive partnerships so passenger and freight services can grow and to be good corporate citizens. Instead, CSX has had a long history of hostility toward passenger rail service.

Recently, CSX told Amtrak it needed $2 billion to accommodate one passenger train every 12 hours on its lightly used railroad from Mobile, AL to New Orleans. Amtrak took legal action against CSX and Norfolk Southern before the federal Surface Transportation Board, a regulatory body, and prevailed. But there are local examples, too.

CSX’s right of way below the Interstate 490 bridge used to have two tracks, including across the Cuyahoga River lift bridge in the background. A study released this past winter recommended restoring the second track through here to keep Cuyahoga Valley Scenic Railroad trains out of the way of CSX freight trains making industrial switching moves in the area (Google).

Fifteen years ago, lobbyists for CSX successfully urged Ohio gubernatorial candidate John Kasich to campaign on giving back $400 million in federal funds for starting passenger rail linking Ohio’s largest cities — Cleveland, Columbus, Dayton and Cincinnati (3C+D), according to since-retired leaders of the Ohio Department of Transportation.

In full disclosure, this author was at the time executive director of the rail and transit advocacy organization All Aboard Ohio. Back then, I was informed by ODOT brass that CSX told them the $400 million wasn’t enough money for track improvements to accept passenger trains on its Cleveland-Columbus portion of the 3C+D route.

Some things apparently never change. Just last week, All Aboard Ohio sent out a press release urging Ohioans to contact their state lawmakers to restore benign language to the state budget to provide just $20,000 per year so Ohio could rejoin the Midwest Interstate Passenger Rail Commission, a coordinating body of state departments of transportation.

The Ohio Senate’s budget bill also removes a legally required passenger rail representative from serving on the Ohio Rail Development Commission — a seat that has existed for over 20 years — and gives it to an out-of-state freight railroad industry representative, even though the industry already has a seat on the commission.

According to a source familiar with the matter, a freight railroad lobbyist was the guilty party behind these moves. NEOtrans will continue to inquire which freight railroad it was.

END