The decommissioning of the old rail fleet – including these Tokyu heavy-rail vehicles on the Cuyahoga Viaduct near Downtown Cleveland – will be a visible reminder of the several improvements under way at the Greater Cleveland Regional Transit Authority to better support Greater Cleveland (NEOtrans). CLICK IMAGES TO ENLARGE THEM.

TOD to be included in updated plan

For a transit agency facing upcoming budget deficits in 2026, the Greater Cleveland Regional Transit Authority (GCRTA) struck a hopeful tone at the first committee meeting of the year. But due to rising costs of healthcare and static ridership numbers, others are sounding the alarm for immediate change to avoid collapse.

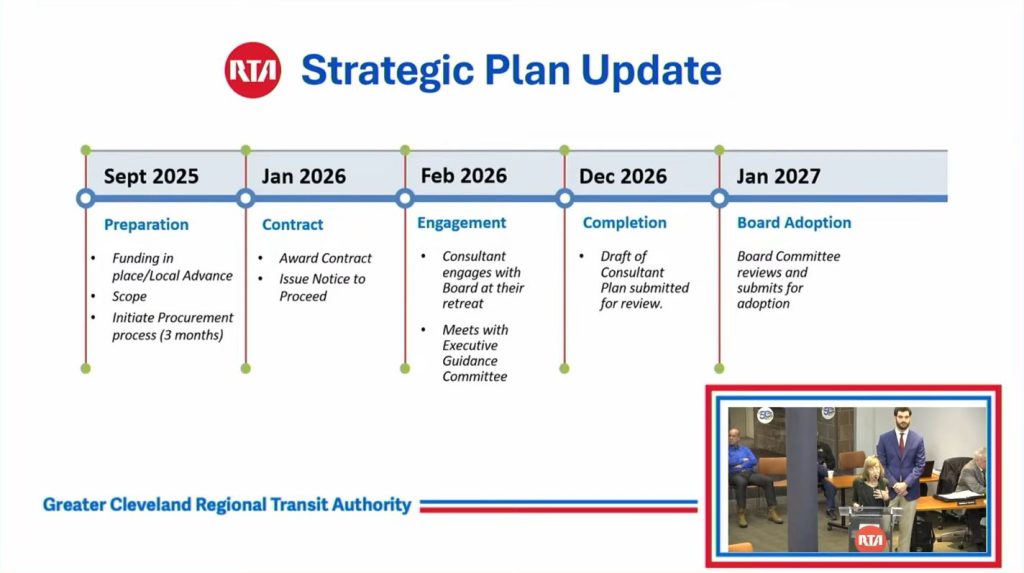

Thus GCRTA officials on Tuesday embarked on a new strategic plan to guide the agency for another decade. Much like a new year’s resolution, the agency and its partners have one year to set goals and chart a new path forward.

GCRTA’s last strategic plan was developed in 2019 – just before the COVID-19 pandemic. A strategic plan is a framework that defines risks, goals, shortcomings and opportunities to guide decisions.

That plan outlined goals through 2030 for an agency with, at the time, ridership nearly twice what it experiences now in a post-COVID world. It included “pillars” – guiding principles and tasks to modernize the system and increase ridership.

Many of those pillars are currently being or have been accomplished, the most significant being the $450 million Railcar Replacement Program. Funded in part with grants from the state and federal government, new Siemens S200 light-rail vehicles are currently in production with the first cars expected to enter service in the Summer of 2027.

In just two years, Cleveland will go from having the oldest rapid transit fleet in the US to the newest. To complement the Railcar Replacement Program, the agency approved several planned improvements to stations and maintenance facilities throughout the network on Tuesday.

Other critical pillars of the previous strategic plan that GCRTA completed include a fare equity study and implementation of the TRACTION metrics system which provides accurate customer survey data and on-board automated ridership counts.

Completing these goals has afforded GCRTA the ability to inform the new strategic plan with recent data. And while they typically commission these strategic plans every ten years, the changing public transit landscape and urgent budgetary needs necessitate immediate action.

So how exactly does GCRTA plan to create its new strategic plan and what recommendations will it include?

It all started back in October of 2025 when the agency issued a request-for-proposals (RFP) seeking a consultant to help draft the new documents. Five firms submitted proposals. Ultimately, it was AECOM Technical Services – with an office in downtown Cleveland – that won out.

At a cost of $465,000, the new strategic plan will be more than $120,000 cheaper to draft than the previous plan. This is due in part to more advanced data available and the need for a more efficient public engagement process.

According to GCRTA’s Director of Planning Maribeth Feke, the new strategic plan will adjust 2026-2030 goals and provide new long-term goals reaching out to 2036. But updating existing goals is only the tip of the iceberg; some wholesale additions are required.

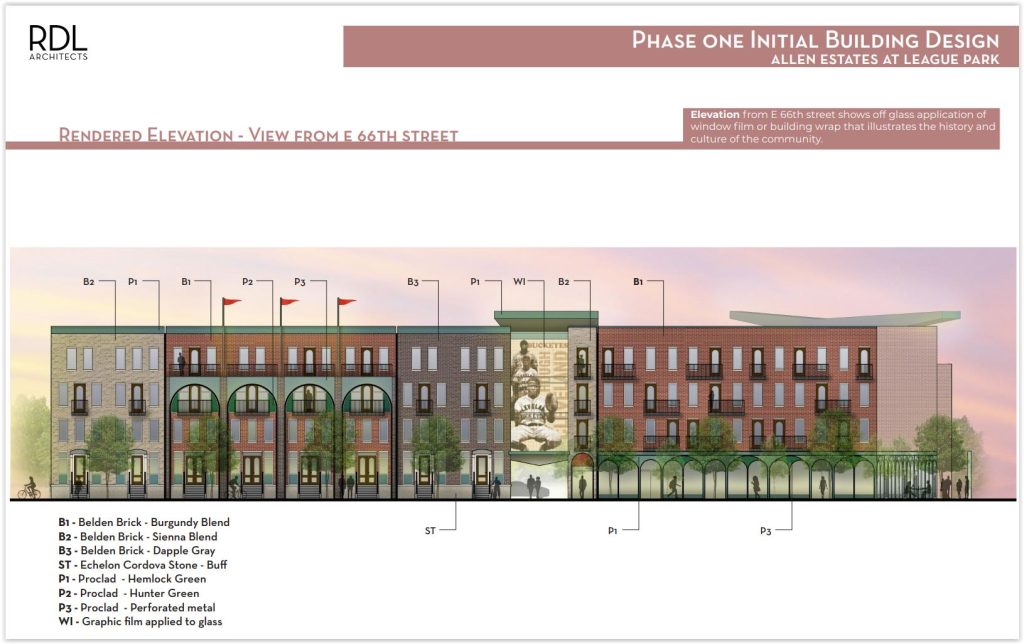

“Transit-oriented development – we’re going to put it on the plan,” she emphasized. “We want to create a chapter that tells us how to grow (TOD) to reinforce what the county has done, the 15-minute city the City [of Cleveland] is working on.”

For example, GCRTA is currently working with the City of Cleveland and their consultants to create a plan for repurposing vacant parking lots at stations along the Airport-Downtown-Windermere Red Line.

Transit advocates argue that helping developers and cities build housing around stations is one of the easiest ways for authorities to increase ridership and revenue.

One aspect working in GCRTA’s favor is that it already owns dozens of acres of underutilized land around its stations. Plus a significant amount of land they don’t own is owned by the City of Cleveland which could be considered a willing participant in TOD.

Vacant land and park-and-ride parking lots can easily be sold off to developers to construct workforce and affordable housing. When transit passes or other subsidies are provided to residents, it can help promote regular ridership.

Other creative funding methods for future projects may be necessary however and will be explored. “We know we’re facing financial challenges. What can we look at to create more revenue from our assets? How do we create funds from those assets whether it be TOD revenue, marketing, advertising,” continued Feke.

She also noted “And if we need to go out to a voter what should that look like? How have other agencies in our state and in our region gotten those (funding requests) through?”

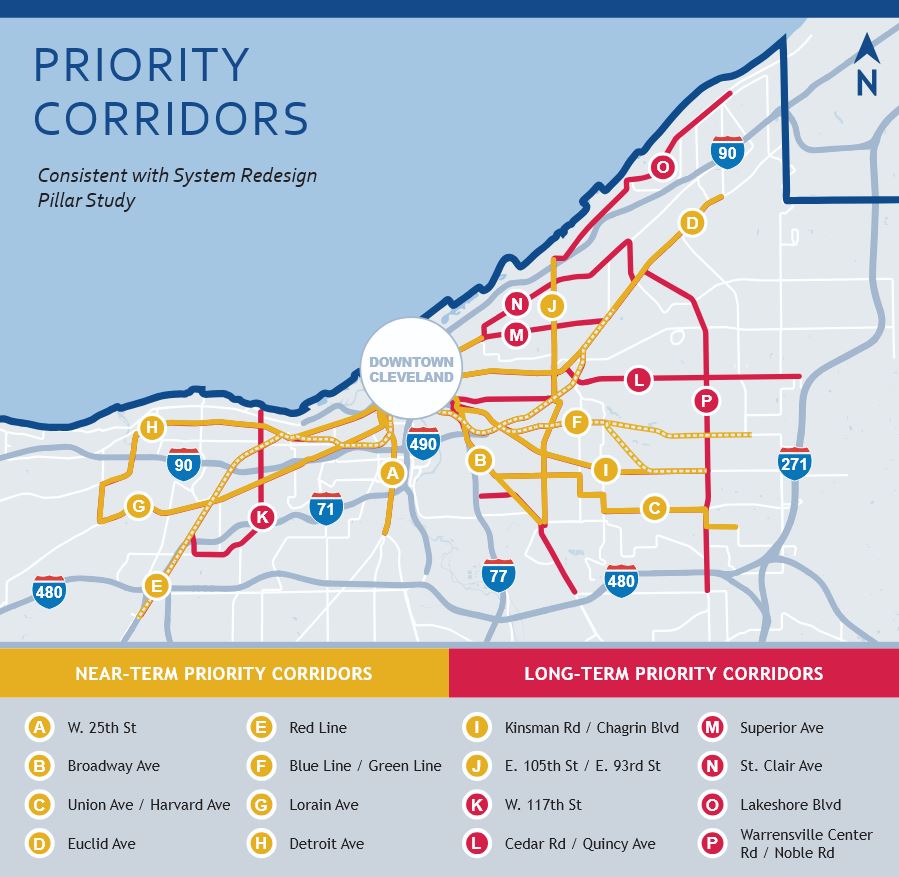

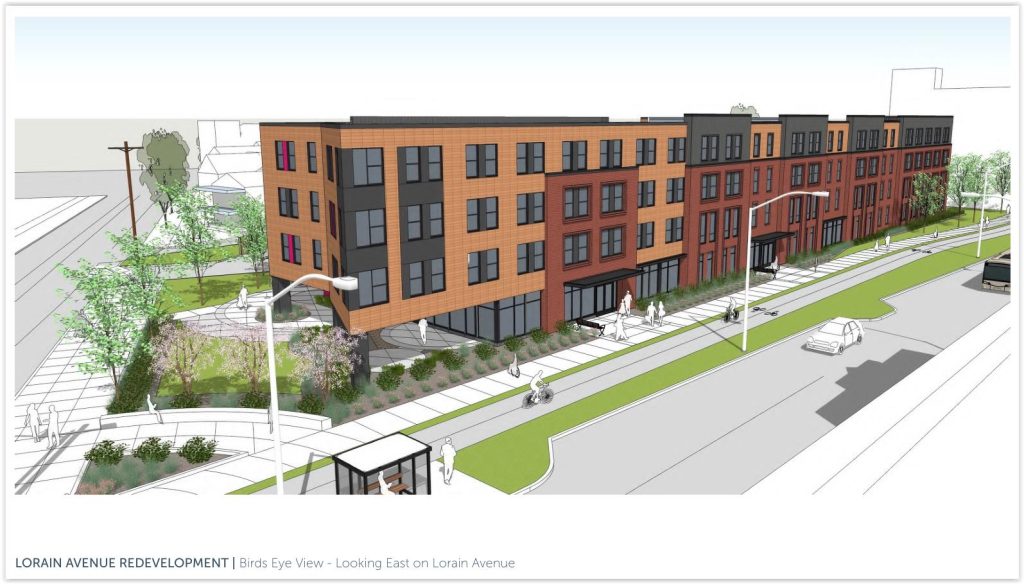

Standard definitions and guiding principles for investing in bus rapid transit will also be included. Corridors like Broadway Avenue will have studies kicking off in 2026 to determine if they are suitable for more rapid forms of transit.

At the same time, construction on a new bus rapid transit for the West 25th Street Corridor is set to begin next year while Warrensville Road, Kinsman Avenue or Detroit Avenue – some other high-priority corridors mentioned by Feke – could be future candidates.

Kickoff of the strategic plan process will commence in February 2026. In December the draft will be presented to the board for consideration. The hope is that by the start of 2027 the plan will be approved.

“I’m excited to be able to initiate this project with the team,” said GCRTA General Manager and CEO India Birdsong Terry, who called the process a “mid-life overhaul.”

By the end of the meeting, the committee challenged its leadership as the agency approaches a critical inflection point: continue to be proactive in any and all discussions with Northeast Ohio development groups, and to complement – not diverge – from their efforts.

That includes regional planning organizations like the Northeast Ohio Areawide Coordinating Agency and Cuyahoga County, the City of Cleveland and even private developers with deep pockets and political sway such as Haslam Sports Group. There is “a lot of work, quickly” that needs to happen, noted Terry.

END