Here are just four of the Greater Cleveland Regional Transit Authority’s 21 rail stations that have park-n-ride lots. All station parking lots are largely devoid of cars since the pandemic. Even before that, most station lots weren’t as full as they used to be. With downtown employment and commuting way down and interest in transit-oriented development up, these large parking lots can be developed with new uses to support regional goals like adding affordable housing, improving access to jobs and reduced emissions (Google). CLICK IMAGES TO ENLARGE THEM.

Adapting rail transit to new realities

A COMMENTARY

In recent months, the Greater Cleveland Regional Transit Authority (GCRTA) has served notice that its rail system isn’t going anywhere. That could be interpreted in one of two ways. In one way, GCRTA plans to invest $540 million by the end of this decade to rebuild its 34-mile rail system including a new, standardized light-rail fleet plus rebuilt tracks and stations on the Red, Blue and Green lines. Greater Cleveland’s “Rapid” is sticking around for decades to come. But taking it another way, there are no expansion plans while ridership on GCRTA buses and trains fell nearly 60 percent from 2013 to 2021 “led” by its rail system which fell even farther, from 9.3 million boardings in 2013 to 2.9 million in 2021.

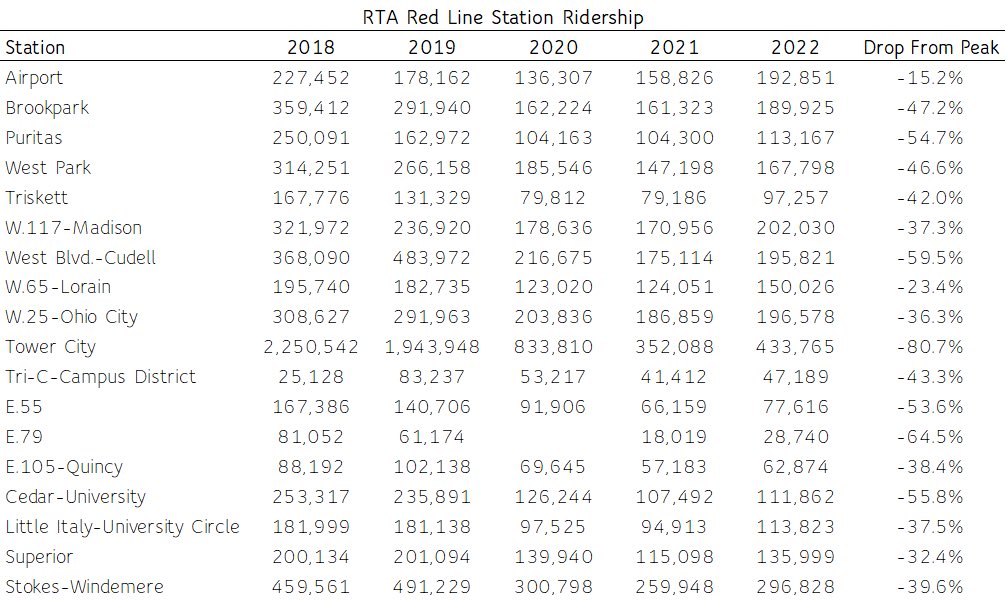

The Rapid was designed primarily to move office workers and other commuters in and out of downtown. One of the most stunning changes since the pandemic isn’t the roughly 30 to 40 percent drop in downtown Cleveland office employment. Instead, it’s the 80 percent drop in train boardings at Tower City Center, GCRTA’s busiest rail station and the main station serving downtown. With one-fifth of GCRTA’s pre-pandemic ridership using its three rail lines, the loss of so many riders has hit the 48-year-old transit agency hard.

GCRTA is no different than most transit agencies in the USA that are facing serious ridership and budgetary challenges. Fare revenues at GCRTA have fallen by more than half, dropping from more than $50 million per year pre-pandemic to less than $25 million now. Before the pandemic, fares counted for about 20 percent of GCRTA revenues. Now they’re only 8 percent, with federal COVID relief funds and a strong recovery of sales tax revenue making up the difference, according to the National Transit Database and GCRTA budget documents.

But GCRTA’s 1-percent countywide sales tax isn’t enough to continue filling the void in the future. When federal relief funds dry up next year, GCRTA is going to need to find other revenue sources or further slash bus and rail services that have already been cut 30 percent in the past 15 years while fares doubled.

“Transit agencies are facing a financial triple whammy – one-time payments from COVID-relief funding are drying up, fare collection has stabilized at well below pre-pandemic levels, and expenses are growing because of inflation, tight labor markets, and supply chain disruptions. As a result, most transit agencies are anticipating a steep, sudden operating budget deficit that will deepen annually, absent other forms of funding,” wrote the TransitCenter in an April 7, 2023 blog about transit’s looming fiscal cliff.

“Robust public transit service is essential for thriving cities and regions where everyone can reach opportunities,” the TransitCenter continued. “But the pandemic has underscored that depending on passengers to keep public transit systems afloat leads to unstable and regressive outcomes. Local, state, and federal governments must contribute substantial, dependable revenue streams for operating transit service in order to weather impending budget crises and to fully realize transit’s potential.”

While the decline in boardings at GCRTA’s main station, Tower City, has been catastrophic, the drop in ridership has been less pronounced at neighborhood stations that don’t rely on park-n-ride lots and downtown commuting for their boardings. There, the train is a part of everyday urban life — not only is it used for going to work or school but for shopping, medical appointments and going out for a bite to eat.

And that’s what should be the case at all stations, including those with now-empty parking lots. Putting more housing, cafes, shops, day cares, businesses, clinics, job training centers and more within a few minutes walk of a rail station would absolutely boost rail ridership on, according to federal statistics, one of the least-used rail systems in the nation. That dense mix of uses in a walkable setting around transit stops is called Transit Oriented Development (TOD).

The Van Aken District at the Shaker Heights end of the Blue Line is what land use densities should look like at more Cleveland-area rail transit stations — mid- and high-rise developments with ground-floor retail, commercial and restaurant spaces. The public sector, starting with landowner GCRTA, needs to lessen the financial risks and legal barriers to encourage such land uses at rail stations (KJP).

The city of Cleveland and Cuyahoga County are trying to support Transit-Oriented Development (TOD) within a five-minute walk of all stops on high-frequency transit routes offering service every 15 minutes or better during daylight hours. That’s called “The TOD Zone.” Cleveland City Council is considering an ordinance that, if adopted, would create a Transportation Demand Management (TDM) program to allow TOD and a reduced amount of parking spaces at new developments in that zone.

The TOD Zone has 78 percent of the city’s jobs (more than 200,000) but only 23 percent of its housing. And 70 percent of those households have zero cars or just one car that is often shared. The lack of transit accessible housing creates a physical disconnect between jobs and job-seekers, worsening poverty and crime. There are 17,000 vacant lots totaling over 2,800 acres in the TOD Zone that, if developed with transit-supportive housing densities of 30 units per acre, it would result in 84,000 new dwellings. With an average household size in Cleveland of 2.4 persons per home, that’s 201,600 people added to within a five-minute walk of a high-frequency transit route.

Transit-supportive housing can also be more affordable than car-dependent housing. Parking is expensive, even though we don’t often charge for it on a per-use basis (if we did, we’d have a lot less parking and more transit/walking). Each parking space in a surface lot costs an average of about $5,000 to build while each space in s parking garage costs $25,000 to $35,000. The goal is to reduce the risk of development for investors and reduce the cost of housing for residents. On average in Cleveland, at least 17 percent of a housing unit’s rent is attributed to parking, city data shows.

Parking is also expensive to GCRTA because, not only is it costly to maintain pavement and storm sewers or plow/salt to remove snow/ice, it also is an opportunity cost. By keeping so many parking lots at GCRTA rail stations rather than offering and incentivizing their development, a choice was made to accept keeping a lot of transit-accessible land inert and desolate. That denies GCRTA revenue from suppressed ridership and fares, but also from development partnerships that are being encouraged by policy and funding from the U.S. Department of Transportation.

Little Italy has a vibrant mix of new and old density around the 2015-built Red Line rail station, to the right of the rail bridge above Mayfield Road. Some of this can be replicated at stations like West Park, West 117th-Madison and Superior by developing their park-n-ride lots and nearby lands (Google).

Little ol’ Youngstown, OH just received a $2.9 million federal grant to redevelop its Federal Street transit bus station with a covered bus loading area, parking garage and future residential building above. Something more substantial and vertical should be considered at GCRTA rail stations. The Federal Transit Administration/Build America Bureau has a lot of incentives to support TOD. So might GCRTA, which could be more prolific than the Cleveland/Cuyahoga County Port Authority as a development financier. Thanks to its permanent sales tax, GCRTA can offer bonds with a lower interest rate than the port which is backed by a renewable tax. Yet the port is a more active development partner.

To its credit, GCRTA has matured its TOD efforts over the years. Earlier efforts to develop its station parking lots were misguided, seeking to develop car-centric buildings that are single-use, low-density buildings with surface parking. They include the day care center at Triskett station, the hotel at Puritas station, post office at West Park, or the thankfully-it-never-happened sprawl-style development planned at the Brookpark station in 2003. Recent efforts are more sophisticated, like the nascent project at the Ohio City Station, the Depot on Detroit Apartments at the West Boulevard Station or the Van Aken District at the Blue Line’s Warrensville Station in Shaker Heights. Too often, however, GCRTA devotes more energy to explaining what it can’t do rather than figuring out what it could.

GCRTA staff didn’t respond to inquiries from NEOtrans regarding the data or comments shared in this opinion piece.

What could GCRTA do? Let’s consider most GCRTA station parking lots as obsolete and potentially developable. Even though rail stations still need some parking and bus access, those can be retained on a portion of the ground level of multi-level parking garages financed by federal funds with GCRTA leasing out the development rights above the garages. The developer/building manager gets their tenants’ parking and transit-access needs provided by others.

GCRTA could encourage developers to respond by conducting all of the costly predevelopment work including neighborhood market studies of residential/commercial demand, geotechnical analyses, and any zoning changes to support dense, mixed-use developments. Then it would offer all of its station properties in a rail-systemwide request for proposals in which respondents could pick one or more stations to design a concept including what needs to be funded by grants and low-income housing credits, how ownership/leasing would be handled, additional property acquisitions by GCRTA for awardees, and what ultimately would be built to satisfy GCRTA’s TOD standards.

The potential development sites at GCRTA rail stations, including underutilized publicly and privately owned properties nearby, is substantial. Consider:

West Boulevard Station

station site bus lanes, parking lot and greenspaces = east property – 113,250 Square Feet or 2.6 acres & west property – 2.9 acres

parking lot only = 46,000 SF or 1.1 acres

West 117th-Madison Station

station site bus lanes, parking lots and greenspaces = 82,500 SF or 1.89 acres

parking lots only = #1 21,777 SF or 0.5 acres AND #2 31,750 or 0.7 acres

Triskett Station

station site bus lanes, parking lots and greenspaces = 259,800 SF or 6 acres

parking lots only = #1 93,300 SF or 2.14 acres AND #2 27,376 SF or 0.63 acres

Horizon Education Center = 2.3 acres and 60 parking spaces 9,000 SF building built in 2019

West Park Station

station site bus lanes, parking lots and greenspaces = 673,800 SF or 14.6 acres

parking lots only = 128,600 SF or 2.95 acres

West Park Post Office = 5.1 acres and 155 car parking spaces 20,260 SF building built in 1998

Beth Hanna former car/motorcycle dealership = 7.95 acres, large unmarked parking area and 58,500 SF of buildings built mostly in 1966

West 150th Station

station site bus lanes, parking lots and greenspaces = 350,100 SF or 8 acres

parking lots only = 78,000 SF or 1.8 acres

ODOT lands including ramps = 15.1 acres and about 270 parking spaces on 83,000 square feet

BFR Cleveland office 13.14 acres, about 1,000 parking spaces (3-level deck behind office building) and 270,000 SF of buildings the largest of which is a 1987-built 239,149 SF office building.

Brookpark Station

station site bus lanes, parking lots and greenspaces = 926,000 SF or 21.2 acres

parking lots only = #1 81,700 SF or 1.88 acres AND #2 176,800 or 4.1 acres AND #3 (west) 115,000 or 2.64 acres (not including highway-isolated site)

highway isolated site = 215,000 SF or 4.95 acres

Ford property = 29,600 SF or 0.68 acres

Here are four sample rail stations with park-n-ride lots and other underutilized publicly and privately owned parcels nearby. Red shaded areas are parcels owned/controlled by the Greater Cleveland Regional Transit Authority. Blue represents publicly owned parcels. Yellow is privately owned but lacks transit-supportive densities despite being adjacent to a rail station (Google-myplace.cuyahogacounty.us).

Superior Station

station site bus lanes

parking lots only = 29,405 SF or 0.68 acres

publicly owned land nearby (county RFP) = 4.25 acres

Windermere Station

station site bus lanes, parking lots and greenspaces = 573,000 SF or 13.15 acres

parking lots only = 111,000 SF or 2.55 acres

publicly owned parcels nearby = 72,000 SF or 1.65 acres

Cleveland Town Center etc = 130,000 or 3 acres

Lee Road Blue Line Station

publicly owned parcels nearby = 681,600 SF or 15.7 acres (not including cemetery)

Kenmore Blue Line Station

publicly owned parcels nearby = 71,000 SF or 1.63 acres

St. Peters Lutheran Church lot = 49,000 SF or 1.1 acres

Warrensville Green Line Station

parking lots only = 48,000 SF or 1.1 acres

publicly owned parcels nearby = station 211,000 SF 4.8 acres – NW 374,000 SF 8.6 acres – N 367,000 SF 8.4 acres – S 130,000 SF 3 acres – SE 977,000 SF 22.4 acres

Green Road Green Line Station

parking lots only = 335,000 SF or 7.7 acres

publicly owned parcels nearby = west 622,000 SF or 14.3 acres – east 1,300,000 SF or 28.2 acres

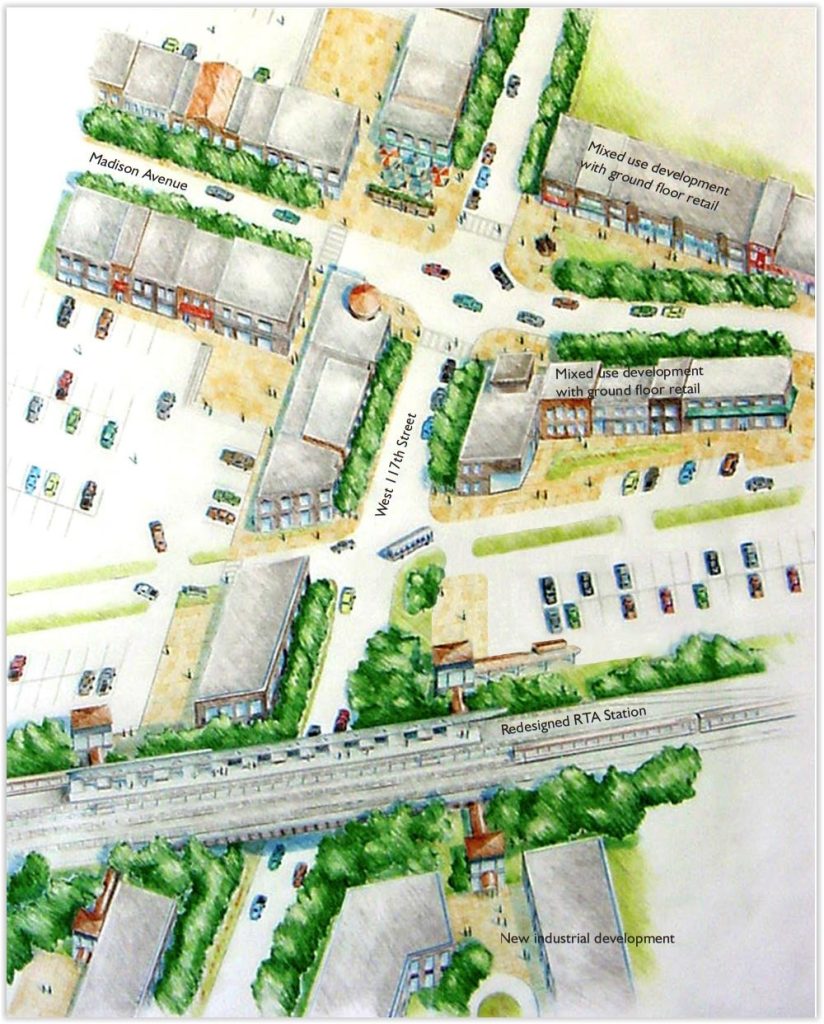

In 1999, Kent State University’s Urban Design Collaborative developed this conceptual redesign of the area surrounding the West 117th-Madison Station at the Lakewood-Cleveland border, a setting that remains far from being transit-supportive. Today, three of the four street corners here are littered with parking lots and single-use structures that don’t support transit use (UDC).

The amount of land devoted to parking lots at these GCRTA rail stations total 30 acres, and all GCRTA properties at those stations total 80 acres. If you add up all GCRTA, adjacent public and underutilized private properties, they total 232 acres. Developed with transit-supportive housing at 30 units per acre, an average household size of 2.4 persons and an average retail square footage of 23.5 square feet per person, each station site becomes populous enough to be its own transit neighborhood. They would also become significant generators of ridership and revenue to GCRTA.

It could have these impacts:

- If GCRTA sought to develop its rail station parking lots only, it would have 30 acres available. They could host from 750 to 1,050 housing units for 1,800 to 2,520 people with 42,300 to 50,588 square feet of neighborhood retail.

- If GCRTA developed all of its properties at these rail stations, it would turn 80 acres into more productive uses. That acreage could host from 2,000 to 2,800 housing units for 4,800 to 6,720 people with 112,800 to 157,920 square feet of neighborhood retail.

- And if GCRTA, plus neighboring owners of public and underutilized private properties developed their lands, a total of 232 acres could host 5,800 to 8,120 housing units for 13,920 to 19,488 people with 327,120 to 457,968 SF of neighborhood retail.

That sounds like a lot of people but it’s really not. It’s like taking downtown Cleveland’s population or Broadview Heights’ and spreading it among these 12 GCRTA rail stations at the most aggressive development scenario. Where would the residents come from? As a real estate local developer once said, with the right marketing, you can convince 1 percent of the population to do anything. The right marketing may be that living in a mid- to high-rise at a GCRTA rail station served by its new trains on rebuilt tracks means living a low-mileage lifestyle where numerous other transit villages with a variety of jobs, schools, shopping and restaurants are just a few stops away, plus the airport and attractions/nightlife at downtown, University Circle and elsewhere.

There’s 2 million people in Greater Cleveland; 1 percent of them is 20,000. That doesn’t take into account domestic and international migration. In post-pandemic America, Greater Cleveland is already seeing the fourth-largest positive migration as a result of remote work. If we keep building housing, that migration may increase with climate change. If we open our door wider, more people will come. The Great Lakes region is considered a safe climate haven and the housing would be built along already existing electrically-powered transit lines. International migrants want to live in an affordable city where they don’t have to drive. And immigrants create more businesses and jobs than natives because they are more willing to take risks.

So not only could more aggressive development of rail station properties help boost GCRTA, it could also help boost Greater Cleveland in an environmentally and financially sustainable way that doesn’t congest our roads with more polluting cars that fewer people can afford. GCRTA is already investing big in its rail system because building a new one would cost billions more. But its historic rail ridership market — downtown commuting — is a hollow shell of what it once was and probably won’t come back. GCRTA needs to acknowledge this and transition its rail system to a new ridership paradigm. Its empty rail station parking areas may offer lots of opportunity.

END