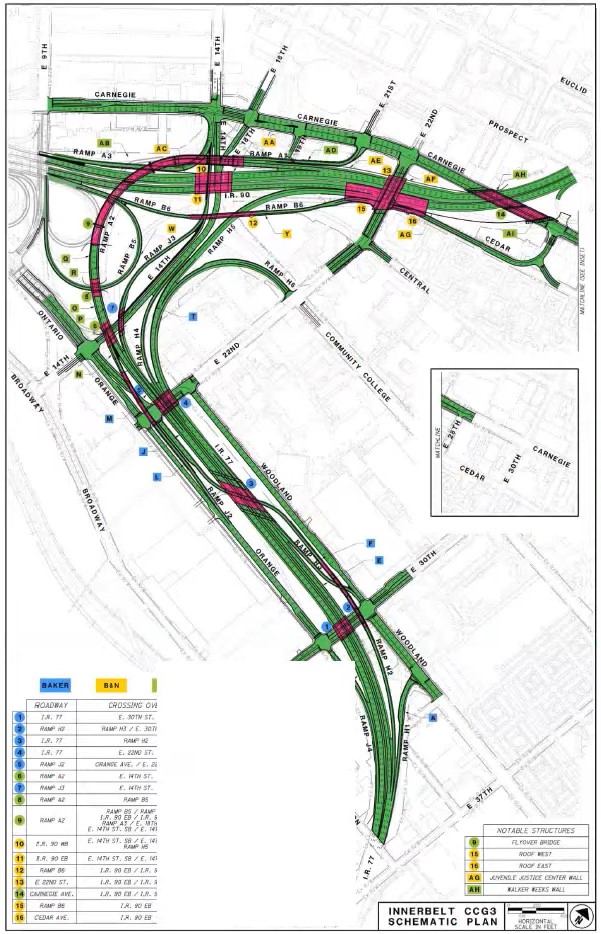

This map shows major roadway improvements for what’s called the “Cleveland Contract Group 3” portion of the Inner Belt highway’s reconstruction in downtown Cleveland. This includes the Central Interchange of Interstates 90 and 77 as well as the downtown approaches for I-77, highway ramps and intersecting streets. The top of the map is north (MBI). CLICK IMAGES TO ENLARGE THEM

Downtown Central Interchange re-do to cost $160 million

Yesterday, Cleveland’s City Planning Commission unanimously tabled a request by the Ohio Department of Transportation (ODOT) for consent to construct improvements to the Central Interchange, where Interstate 77 ends and connects with Interstate 90 in downtown Cleveland. The reason given was to have a “deeper conversation” with City Council which ultimately must vote on the consent request about how the project can right the wrongs of the past including using highways to divide minority neighborhoods from downtown.

Ohio municipalities determine how land in their jurisdictions are used. And in land use matters, the planning commission advises city council and refers to it ordinances such as this, which can be amended, supported or opposed. ODOT requested a supportive vote from the planning commission. But commission members told ODOT “not so fast.”

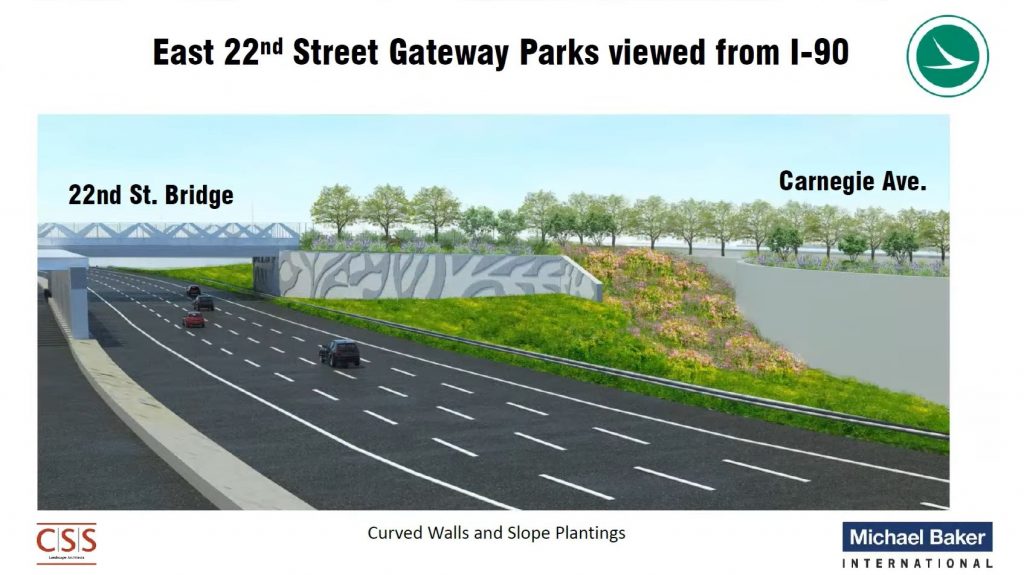

Starting in 2024, ODOT wants to rebuild and redesign the Central Interchange with soaring and more gently curving ramps to allow vehicles to safely travel through them at higher speeds so traffic moves more fluidly. To be eligible for federal highway funds, road projects must improve safety and the flow of traffic. This project will also involve replacing the Carnegie Avenue and East 22nd Street bridges over I-90 along while constructing soaring bridges for a ramp from I-90 west to I-77 south and for an exit ramp from I-90 eastbound to the Carnegie/East 22nd/Cedar Avenue area.

The latter ramp, called “Ramp B6” on ODOT planning documents, may be redesigned to accommodate new structures as part of the St. Vincent Charity Medical Center campus masterplan including a repurposed Cuyahoga County Juvenile Courthouse and Detention Center on East 22nd at Cedar, according to city planning officials.

The rebuilt and redesigned Central Interchange is a roughly $160 million project and represents the fifth phase of ODOT’s Inner Belt highway reconstruction program. Starting in 2009, the first two phases were the new eastbound and westbound bridges over the Cuyahoga River valley costing $634 million. The next two phases involved replacing I-77’s bridge over I-490 and Broadway Avenue’s bridge over I-77 for $60 million, while redoing the interchange between I-71 and State Route 176 (Jennings Freeway) cost $5 million, according to ODOT.

The Central Interchange portion of the Inner Belt program may be one of its most controversial primarily because of its history. The Central Interchange and its various highway approaches were built in the late 1950s, wiping out much of the Central neighborhood, Cleveland’s oldest and, at the time, largest African-American community. Many have since called the roadways a physical, visible form of red lining to separate poor, minority neighborhoods from more affluent white ones — in this case, downtown Cleveland.

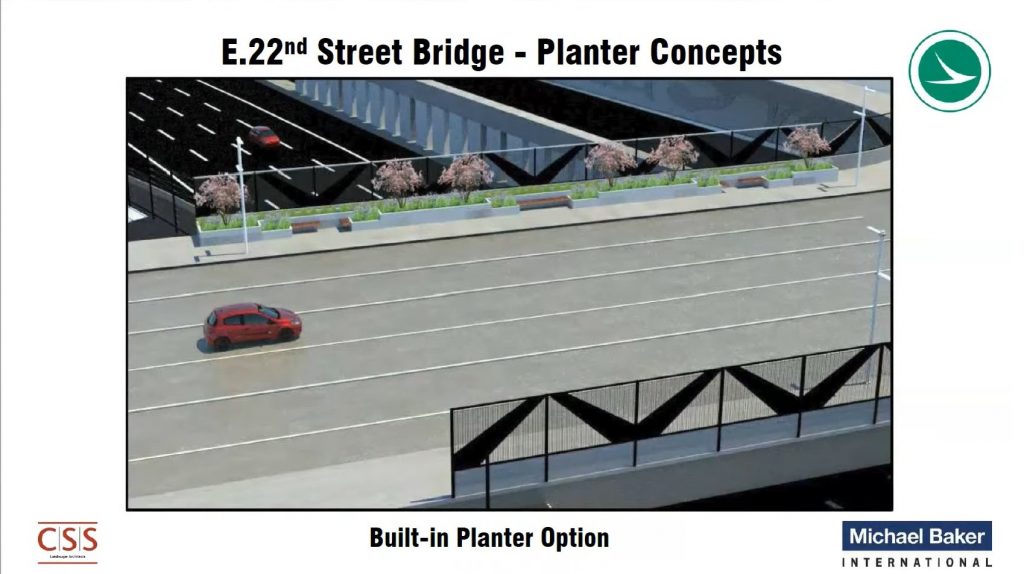

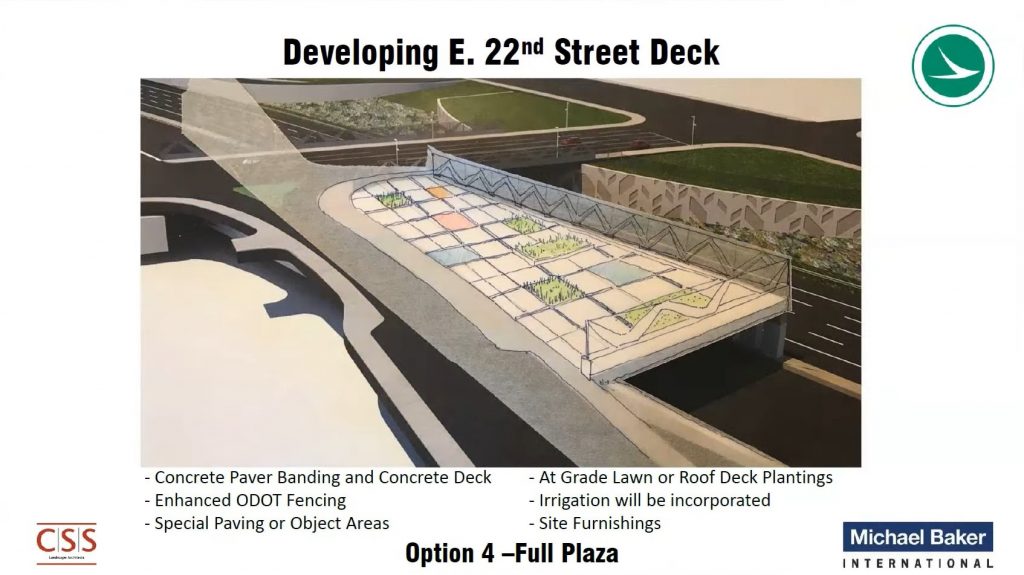

This view of the proposed East 22nd Street bridge deck over Interstate 90 shows the pedestrian enhancements on the east side of the bridge only. Beyond it is the highway including a structure to help support a connecting roadway to Cedar Avenue. That structure is also proposed to support a plaza over part of the highway (MBI).

Ward 17 Councilman Charles Slife, city council’s representative on the planning commission, said that while he was on his way to City Hall for the commission meeting, he was reminded of his belief that too much public money was going to highways while other modes of transportation that everyone can use are neglected.

He was delayed while on the Red Line rapid transit operated by the Greater Cleveland Regional Transit Authority (RTA) which can’t afford to replace its four-decade-old trains. Different trains had to be evacuated 18 times in 2021 due to smoky fires from aging electric motors, according to Clevelanders For Public Transit. In addition to the Red Line trains, railcars on the Blue/Green lines linking Shaker Heights and downtown are even older and break down frequently as well. Cost of replacing the entire rail fleet is $300 million and will take up to eight more years with known, limited resources.

And while on the Red Line, he was passed on the adjacent Norfolk Southern freight tracks by one of the Amtrak passenger trains from Chicago. It was running three hours late despite leaving Chicago on time, according to Amtrak’s Train Tracker, but soon encountered significant freight train traffic congestion across Indiana and Ohio. The Northeast Ohio Areawide Coordinating Agency is leading a multi-agency effort to find planning funds to determine how to reduce rail traffic congestion between Cleveland and Chicago to improve freight and passenger reliability and to expand rail services.

In the late 1950s, construction of the Central Interchange and related urban renewal projects swept away much of Cleveland’s largest African-American enclave, the Central neighborhood, which had a population of 100,000 in 1940 and just 10,000 by the end of the 20th century. Many relocated to the Hough and Glenville neighborhoods causing crowded housing, racial unrest, violence, white flight and economic isolation of the poor (KJP Collection).

“There’s so many transportation projects around the state,” Slife said. “It just seems that ODOT keeps coming forward with overbuilding our interstate system that has traffic for maybe five hours a week. I guess to me it feels like a waste of taxpayer dollars when there’s so much to be done and knowing that the next ask down the road is going to be to go back to the days of urban renewal and take out buildings so that we can mitigate Dead Man’s Curve when the truth is that it’s just an urban condition. You go to any other city and there’s more traffic, there’s tight ramps. Why do we keep designing everything so that we can go 80 mph? It’s just frustrating to me.”

Future phases of the Inner Belt program include easing Dead Man’s Curve for nearly $500 million, redesigning the Inner Belt trench between the Central Interchange and Dead Man’s Curve for about $400 million, and reconstructing I-71 north of West 25th Street for about $200 million, according to ODOT estimates. Total cost for all phases of the Inner Belt renewal program could amount to $1.8 billion.

A similar debate occurred in Milwaukee less than a decade ago when the Wisconsin Department of Transportation (WisDOT) funded a $1.7 billion expansion of the Zoo Interchange near downtown Milwaukee. Urban minority groups filed suit saying that their jobs-access needs were being neglected. WisDOT settled the lawsuit by providing $13.5 million to expand bus routes in Greater Milwaukee.

City Planning Commission Chair Lillian Kuri said she would feel different about the Central Interchange project if it did more than just pay attention to moving cars but also funded other modes of transportation. That included improved pedestrian access that reconnected parts of the city that were divided by the highway when it was built 60 years ago.

“As things come in the future, for me, if the leaders, the designers and those who are setting the charge of the projects do it from an opportunity to repair wrongs and to reconnect our cities then I think it’s a different story for me,” Kuri said. “That’s just not the charge of this project and the resources that have been allocated to it. So I think sometimes it matters how the projects are being designed and led and thought through and what the values are of what you’re trying to accomplish with them.”

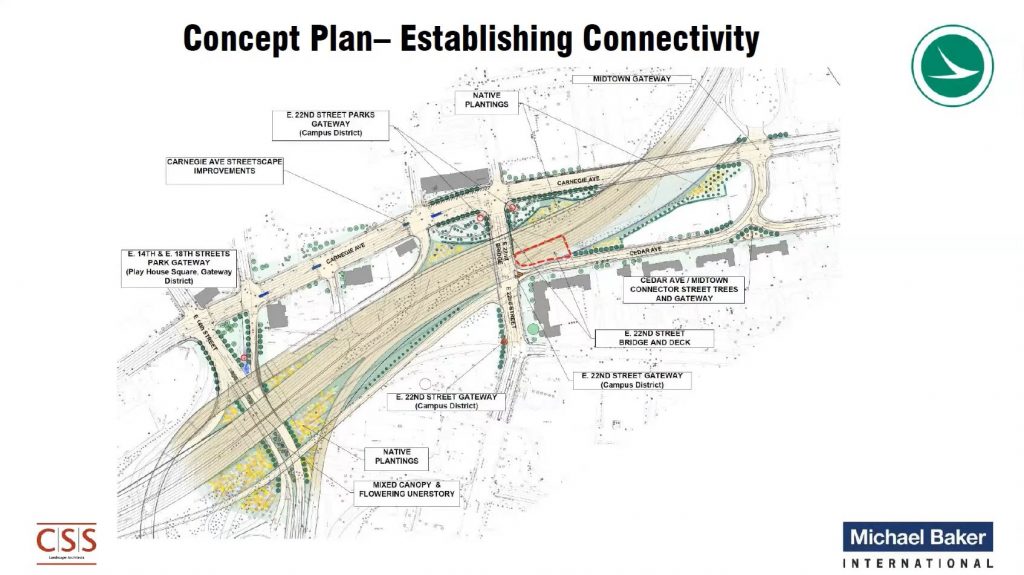

Derek Johnson, a project manager at ODOT consultant Michael Baker International, said meetings were held with community stakeholders from the city, county, institutions, community development corporations and others whose jurisdictions are near the affected highway project. He said the proposed redesign of the East 22nd bridge and its environs are a result of that input.

The new East 22nd bridge, after removing the Cedar highway overpass, would have a wider sidewalk with landscaping along it. On either side of East 22nd, between I-90 and Carnegie, a Gateway Park would be provided. And, if another agency funds its ongoing maintenance, ODOT would build a deck over the eastbound lanes of I-90 on top of which would be a public plaza. Last September, ODOT’s Transportation Review Advisory Council awarded the Central Interchange project $185.9 million.

The Central Interchange project is located almost wholly within the Campus District Inc.’s service area. Its Executive Director Mark Lammon said he was grateful for ODOT’s proposed improvements but urged it to do more including supporting more public transit. For example, Campus District has been pushing for the reactivation of a long-shelved project that would extend the Waterfront Line as a light-rail loop of downtown that also would serve the Central neighborhood.

“Campus District views the East 22nd Street bridge as a vital link to connect the Central neighborhood back into downtown and begin to mend the wounds that created by the highway,” Lammon said. “We are also supportive of helping rebuild and expand our public transit network. We hope both projects receive the attention they deserve.”

END

- Michael Symon joins River Roots’ move to Flats

- Tenant ID’d for big new industrial development near Hopkins airport

- $119M Lakewood Common project goes vertical

- CWRU to renovate, expand one of its most historic buildings

- Master Chrome coming down, cleaning up

- Familiar Ohio City buildings go on sale for the first time in 143 years