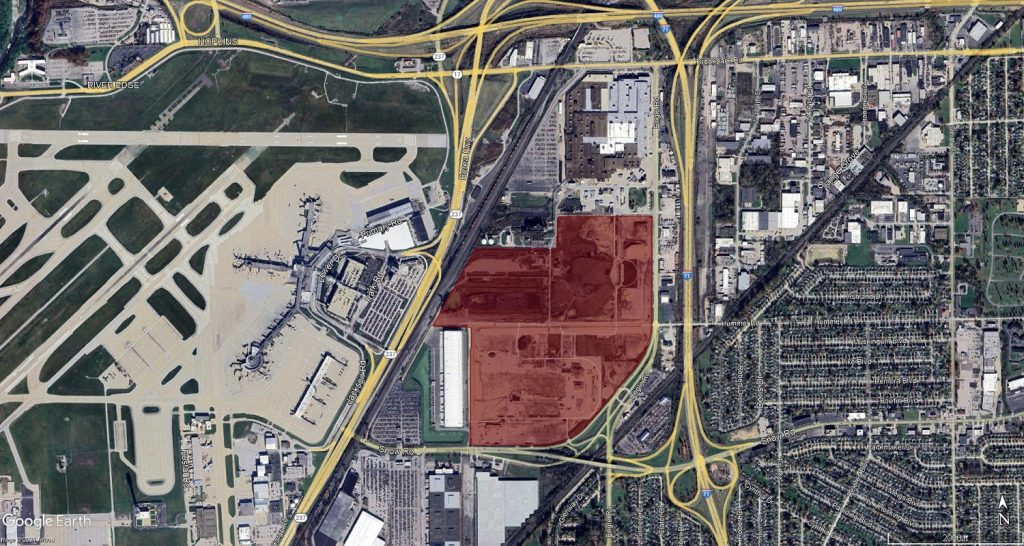

This is the 210-acre Forward Innovation Center-West in the Cleveland suburb of Brook Park, next to Cleveland Hopkins International Airport. Several sources say the owners of the Cleveland Browns are acquiring most of this property, leading to speculation that this site could be the location of a new football stadium and supportive development, absent an intensified effort by the city of Cleveland to retain them (Weston). CLICK IMAGES TO ENLARGE THEM.

Airport-adjacent site is under contract

ARTICLE UPDATED FEB. 9, 2024

The owners of the Cleveland Browns football team have reportedly reached a purchase agreement to acquire a large piece of land in the Cleveland suburb of Brook Park, leading to speculation that the Browns could leave the city of Cleveland for the second time in the team’s 78-year history.

According to three sources who spoke to the breaking news real estate blog NEOtrans (North East Ohio transformation) on the condition of anonymity, the Haslam Sports Group has a contract to buy a 176-acre parcel that’s 9 miles southwest of Downtown Cleveland. It is about 1,000 feet from Cleveland Hopkins International Airport, located on the other side of Ohio Route 237 and the Norfolk Southern railroad tracks.

It remains to be seen what is the purpose of the reported Brook Park purchase agreement. It may be a genuine attempt by the Haslam Sports Group to build a football stadium in Cleveland’s suburbs. It could also be an insurance policy by the Haslams in case talks with city of Cleveland officials fail to produce a deal very soon for the renovation of the city-owned Cleveland Browns Stadium on downtown’s lakefront. The Browns’ lease at the stadium expires after the 2028 football season.

In fact, the sources did not even say if the property is for a new stadium, but it is big enough that it certainly meets the criteria for one. That criteria is a level, 100-plus-acre site with good transportation access. This site exceeds those requirements as it is within walking distance of the airport, accessible to Route 237, Interstates 71 and 480 plus the Greater Cleveland Regional Transit Authority’s Red Line rail rapid transit.

Formerly the site of two Ford Motor Company plants, and next to a third Ford plant that remains active, the nearly 210-acre property is being redeveloped by a mostly local consortium as the Forward Innovation Center-West, 18300 Snow Rd. A 33-acre parcel was carved out for the first tenant of the business park — a roughly 370,000-square-foot Amazon distribution center that opened about one year ago.

Developing the Forward Innovation Center-West is a partnership of Weston, Inc. of Warrensville Heights, the DiGeronimo Cos. of Independence and Scannell Properties of Indianapolis, IN. They created a joint venture called DROF BP I LLC (spells “Ford” backwards and “BP” referring to Brook Park) which purchased the land in April 2021 for $31.5 million, according to county records.

“We’ve been clear on how complex future stadium planning can be,” said Cleveland Browns Senior Vice President of Communications Peter John-Baptiste in a written statement. “One certainty is our commitment to greatly improving our fan experience while also creating a transformative and lasting impact to benefit all of Northeast Ohio. We understand the magnitude of opportunity with a stadium project intent on driving more large-scale events to our region and are methodically looking at every possibility.”

“We appreciate the collaborative process with the city of Cleveland and the leadership of Mayor Bibb in analyzing the land bridge and renovating the current stadium,” John-Baptiste added. “At the same time, as part of our comprehensive planning efforts, we are also studying other potential stadium options in Northeast Ohio at various additional sites. There is still plenty of work to do and diligence to process before a long-term stadium solution is determined and will share further updates at the appropriate time.”

In a NEOtrans interview, a real estate insider speculated last summer that the Brook Park site would be among several considered by the Browns if negotiations with the city of Cleveland failed to produce a cost-sharing deal in a timely manner for a nearly $1 billion renovation of the 1999-built, 67,431-seat stadium.

City of Cleveland officials were apparently unaware of the pending purchase, with Cleveland Press Secretary Marie Zickefoose telling NEOtrans earlier this week that “It is my understanding that we continue to have positive and productive talks with HSG/Browns. That’s all I am aware of.”

“Keeping the Browns at home on the downtown Cleveland lakefront is a priority for Mayor (Justin) Bibb and city leadership,” said city of Cleveland Chief of Staff Bradford Davy later added. “We understand and respect how complex this process is and appreciate the partnership we’ve had and will continue to have with the Browns and Haslam Sports Group (HSG). The administration has developed a strong, thoughtful and comprehensive package that we believe respects taxpayers and protects the city’s general revenue fund while meeting the needs expressed by the team.”

Davy explained that this has been shared with the HSG team during the city’s “extensive negotiations” over the last eight months. The city said they continue to meet with HSG to refine their terms and come to “a shared vision and acceptable deal for both parties” that improves the experience for residents, sports fans and visitors, he said.

A city of Cleveland source said that it’s unlikely the Haslams would secure a purchase agreement merely to motivate Cleveland city officials to move faster or to pursue a better deal for the Haslams. The reason is that city officials didn’t seem to know about the Brook Park agreement. Leverage works only if the target is made aware of it.

An overhead view from Nov. 5, 2023 of the site on which a professional football stadium, parking and supportive developments like hotels and shops could easily fit. That 176-acre site is shown in red. Three highways and two busy railroads surround the site, which is also next an international airport and a rapid transit line into the city (Google).

“No one is scrambling” to respond to any purchase agreement, the source said. He assured NEOtrans that city officials want to keep the Browns in Cleveland. Losing the team again, even if to a suburb, would be an emotional issue for Cleveland residents and a loss of prestige for the city, regardless of any positive or negative fiscal impact on the city.

Interestingly, 12 of 32 NFL teams already play their home games in suburban municipalities. That number would grow to 13 if the Chicago Bears follow through in possibly moving from downtown to Arlington Heights. Several other teams play within the city limits of their metro area’s “mother city” but not downtown, such as the Tampa Bay Buccaneers, Philadelphia Eagles and Green Bay Packers.

NEOtrans sent e-mails seeking confirmation and comment to Brook Park Mayor Edward Orcutt and Weston’s President of Acquisitions & Development T.J. Asher. None have responded to the e-mails to dispute or confirm the information prior to publication of this article. NEOtrans’ tracking program shows that someone had opened each of those e-mails.

City, county and state officials have been engaged in negotiations with the Haslam Sports Group led by the husband-and-wife team Jimmy and Dee Haslam. The clock is ticking on the team’s 30-year lease with the city for use of the 25-year-old Cleveland Browns Stadium on the lakefront.

With the Browns’ lease due to expire after the 2028 football season, funding procurement for a new or renovated stadium and design work would have to begin soon. But that work would need to start sooner if the Browns have to build a new stadium.

Construction of a new stadium could take about three or four years while renovations might need two offseasons — after the 2027 and 2028 seasons. Typically, it can take up to a year for a purchase agreement to close and result in a deed transfer. It is not known when the the agreement was signed. And not all land contracts result in a purchase.

In July 2023 and again in September, NEOtrans reported stadium negotiations were faltering. NEOtrans shared insights from two sources, one a city of Cleveland source and the other a Browns source, who said a deal had to be done in “a matter of months, certainly less than a year” to keep the Browns in Cleveland.

“The only thing Dee and I would say for sure is we’re not leaving Northeast Ohio, that’s for sure,” Jimmy Haslam said in July 2023. “Our preference is for us to be on the lakefront. But we’ve got to see how things play out. It will be fluid. There will be bumps in the road and it may be different in three months than it is now.”

But Cleveland city officials are under pressure from constituents to invest more in public safety, infrastructure, housing and other neighborhood quality-of-life issues. If a football stadium is to be renovated, many residents said the city should share that cost burden with more of Northeast Ohio’s political jurisdictions. A recent Scene Magazine article noted that only 15 percent of Browns game attendees reside in the city of Cleveland and 31 percent live in Cuyahoga County.

In November 1995, a county-wide vote was held to extend by 10 years a “sin tax” on alcohol and tobacco products to pay for stadium renovations supported by then-Browns owner Art Modell. Instead, just days before that vote, he announced he would take the Cleveland football franchise to Baltimore after the 1995 season. The sin tax extension passed with 70 percent of voters in support. Lawsuits from the city and the fans forced the Browns’ name, colors and history to remain here.

The sin tax, generating about $14 million per year, was used by the county and city to build for the new Browns a new lakefront stadium that opened in 1999. That project also tapped parking tax revenues, state dollars and a funding contribution from the NFL. Those financial resources may be on the table again but another sin tax extension is more complicated.

With the sin tax due to expire, 56 percent of Cuyahoga County voters in 2014 extended the tax another 20 years to help the Cavs basketball and Guardians baseball teams fund their facilities’ improvements. If the Browns want to tap the sin tax again, it would have to be extended by voters before it expires in 2035. But the Haslams could provide a significant, private-sector contribution to any stadium project.

The Haslam family, including Jimmy and Dee Haslam, sold to Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway an 80 percent stake in Pilot Travel Centers, the largest U.S. truck stop chain, for $11 billion in two separate deals, in 2017 and 2023. Sale of the remaining 20 percent stake was cleared when a lawsuit was settled last month regarding the valuation of the remaining stake which was estimated at $3.2 billion.

A new, open-air, 60,000- to 70,000-seat stadium could cost up to $2 billion to build. Stadiums with a lid cost even more — $2.5 billion for a fixed-roof venue, or at least $3.5 billion for a stadium with a retractable roof.

NFL owners are extremely competitive with each other, not only with the teams they put in their stadiums but among the stadiums themselves. The backers of each new stadium try to outdo ones that came before in terms of design, technology, amenities for fan experiences and for attracting players.

Owners also are increasingly providing “ballpark villages” around their teams’ stadiums as well as their practice facilities, offering hotels, luxury apartments, shopping, wellness centers, digital gaming and other interactive, fan-friendly sports venues.

The stadium situation apparently does not affect the proposed expansion and development of the Browns’ practice facilities in Berea, called the CrossCountry Mortgage Campus. It is less than two miles from the Forward Innovation Center-West site in Brook Park. The area for the expanded practice facilities and potential supportive mixed-use developments grew to 34 acres last fall and could grow further.

The Brook Park site’s proximity to Cleveland’s airport, if developed with a football stadium, could provide the Browns with an amenity that no other NFL team could match. By constructing a new long-term airport parking garage with a 1,000-foot-long enclosed walkway extending over Route 237 and the railroad, it could connect the city of Cleveland-owned airport with a new football stadium’s facilities.

In other words, someone could walk from their airplane seat to their stadium seat and without ever going outside. This year, the city of Cleveland is about begin design work for Cleveland Hopkins International Airport’s $3 billion Terminal Modernization Development Program that could including new roadways, walkways, parking and rental car areas, better transit access, hotels and, of course, terminal facilities.

Previously, the Forward Innovation Center-West was home to Ford Motor Company’s 1.7-million-square-foot Ford Engine Plant No. 2 and its neighboring Cleveland Casting Plant. The casting plant was demolished in 2013 and Engine Plant No. 2 was razed in 2021. Both are just south of a remaining Ford factory, Engine Plant No. 1. Forward Innovation Center-East, another former Ford auto plant but in the southeast suburb of Walton Hills, is also being marketed by the same partnership.

In Downtown Cleveland, Mayor Justin Bibb’s administration has been pursuing a redevelopment of the Lake Erie waterfront with recreational facilities, housing and shops. It would be connected to the central business district and the riverfront via pedestrian accessway called the North Coast Connector over the Shoreway highway.

The Shoreway is proposed to be downgraded from a highway into a boulevard. The connector would cross the roadway and the lakefront railroad and light-rail transit tracks. And it could link up with a multimodal transportation center served by Greater Cleveland Regional Transit Authority light rail trains and buses plus Amtrak trains. Final designs for the “Shore to Core to Shore” vision are to be released early this year.

Conceptual lakefront plans released in October showed a renovated football stadium but offered little detail about it. On Feb. 1, city and county officials were in Washington DC to lobby the departments of Commerce and Transportation for hundreds of millions of federal dollars for lakefront infrastructure investments. County Executive Chris Ronayne was among those on the trip.

“The city of Cleveland requested that Cuyahoga County join them in Washington, D.C. to make a presentation on the Shore to Core to Shore Vision, which the county supports,” said county Director of Communications Kelly Woodard. She said county officials are unaware of the Haslam’s reported Brook Park land purchase agreement.

The state of Ohio’s draft capital budget also has $20 million in it for the Shore to Core to Shore plan, including the North Coast Connector. When addressing the difficulties in the stadium negotiations with the city last year, Dee Haslam said the lakefront improvements are needed with or without the football stadium — seemingly setting the stage for what appears to be happening now.

“Outside of us (the Haslam Sports Group/Browns), the lakefront in Cleveland has to be developed,” she said. “You need a vibrant city. That’s a really important part of who Cleveland should be. We think the connection bridge has to happen regardless of what happens with our stadium.”

Davy credited the city’s collaborative effort with the Haslams is what produced the $20 million earmark for improving lakefront access.

“The experience of Cleveland residents and visitors to our city is top of mind for us and we are committed to developing our North Coast Lakefront into a world-class, well-programmed, people-focused space and we see the activation of Browns Stadium as a key part of that vision,” Davy said. “The mayor’s commitment to a vibrant shore-to-core-to-shore plan for Cleveland is steadfast and gaining momentum. Downtown Cleveland is such an integral part of the game day experience and the transformational changes on the horizon promise to make that experience even better.”

Dick Clough, executive board chairman of the lakefront advocacy group Green Ribbon Coalition, said the lakefront would be better off with year-round uses like recreation, residences, hotels and shops rather than the seldom-used football stadium dominating it.

“I never liked the stadium on the lakefront,” Clough said. “It ruins the scale of everything else down there. It’s just a huge rectangular thing that dwarfs everything else nearby including the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and the Great Lakes Science Center. If you’re going to lose a team to the ‘burbs, the Browns would be the one to lose. It’s only 10 games (per year) and maybe a concert or two.”

END