|

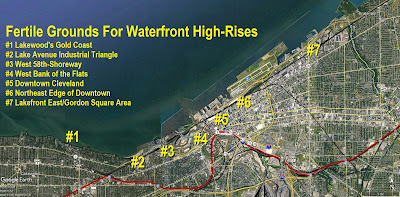

| The above map shows areas highlighted in this article about existing and proposed concentrations of waterfront high- rises in and near downtown Cleveland (Google). CLICK IMAGES TO ENLARGE THEM |

Coastal cities have one thing in common – a tendency to build more high-rise buildings along their waterfronts. In real estate, where location is all-important, few things attract investment more than an accessible waterfront. That’s true for shorelines on oceans, Great Lakes and major rivers.

But in Cleveland, which grew up in the 1800s as an industrial power, it turned its waterfronts over to industry, shipping and railroads. They were what drove Cleveland’s growth until the middle of the 20th century. The decision limited lake access to the public and thus the development of housing, especially the high-rise kind.

Now, in post-industrial Cleveland, everyone from politicians to developers to civic-minded activists to environmentalists are trying to claw back the city’s waterfronts from the relics of industry. That is sure to draw more housing investment to within an easy walk or bike ride of Cleveland’s waterways.

All of this is set against the backdrop of a sub-plot of climate change which could push some southern or eastern coastal residents to northern coastal refuges on the Great Lakes. And the Great Lakes themselves are affected by climate change. They are experiencing record high water levels, driven by increasing precipitation as measured over the decades.

Work by Cuyahoga County and affected communities has started on a 30-mile-long cross-county trail along Lake Erie’s shoreline. The trail’s goal is two-fold — to strengthen the shoreline thus protecting property owners from further erosion and to improve public access to Lake Erie. In other words, cities and the county are offering erosion protection in exchange for public access to the lake.

The work actually started several years ago in the City of Euclid where nearly 1 mile of lakefront trail and erosion control has been built or is under construction. The work will increase the amount of publicly accessible lakefront in Euclid from 5 percent to 30 percent, including the area below multiple high-rises in the vicinity of Kenneth J. Sims Park.

Lakewood also created a lakefront trail below Lakewood Park, highlighted by the Solstice Steps. The next section of lakefront trail and erosion control to see construction could be below Lakewood’s Gold Coast — Greater Cleveland’s largest collection of residential high-rises along the lakefront. But no high-rises have been built here since 1980. That could change with more lakefront access.

Several aging, non-descript buildings that are only 2-3 stories tall on the south side of Edgewater Drive in Lakewood could be replaced by taller buildings. Some of those properties have been eyed by real estate developers proposing high-rises that are taller than the shortest buildings on the north side of Edgewater or are positioned so that their residents could see between lakefront towers to view Lake Erie.

Not all lakefront land is fertile ground for high-rise development. For example, Cleveland’s Edgewater neighborhood just east of Lakewood’s Gold Coast is hostile to the development of more multi-family development. That is due to decades of efforts by the Edgewater Homeowners Association, some of whom have political connections. I wrote about those efforts for Sun Newspapers in 2013.

The neighborhood’s hostility toward high-rises goes back to 1979 when the association won a landmark court case in 1979 against Xen Zapis, developer of the West Chateau apartments, 10301 Lake Ave. The Edgewater Homeowners Association fought Zapis attempt to build more highrises along Lake Avenue, this time east of West 116th Street. The homeowners prevailed.

So finding a spread of land where there are few or no resident NIMBYs nearby might present more fertile ground for high-rises. There is such a place, between the stable Edgewater neighborhood to the west and the rapidly growing Gordon Square/Battery Park neighborhood to the east.

That place is just south of Cuyahoga County’s second-longest stretch of continuous publicly accessible shoreline — Edgewater Park (second only to East 55th Street Marina/Gordon Park/Cleveland Lakefront Nature Preserve). The Lake Avenue industrial triangle is one of the largest surviving industrial areas on the west-side lakefront.

The roughly 30-acre triangle is bounded by Lake Avenue, a busy railroad line and the Gordon Square/Battery Park area to the east. In it are viable industries like Alcon Industries, Universal Grinding, Lowe Chemical or Mid-American Construction. Some of these companies’ facilities are more than a century old, such as Lowe Chemical’s well-maintained, three-story, 112-year-old brick structure at 8400 Baker Ave.

But the triangle also has 20 houses, several small walk-up apartment buildings, and the 78th Street Studios — the largest fine arts complex in Northeast Ohio. It was built in 1905 as the Baker Electric Motor Vehicle Co. factory at 1300 W. 78th.

The Lake Avenue triangle is also one of three areas where the City of Cleveland will introduce its form-based zoning code pilot, NEOtrans reported. Form-based zoning is driven by an urban area’s physical form, not by its type of land use. So if industries want to stay, they can. If developers want to expand residential uses here, they can do that too.

Considering the potential high cost of acquiring, clearing and cleaning up the industrial triangle’s properties, only large-scale developments might be feasible here to generate enough to revenue to offset those costs. These factors, plus the site’s proximity to Lake Erie and Edgewater Park as well as its lack of NIMBYs, are why this site might be suited to high-rise development.

Moving farther east, the next fertile ground for high rises would probably be east of the already extensively developed Battery Park. It starts in the area of the former Westinghouse plant on West 58th Street. The plant itself features a mid-rise building — an eight-story structure that’s been considered for residential conversions.

But the high cost of redeveloping the site has stalled such plans. Like the industrial triangle to the west, a large-scale development here might generate enough revenue to overcome those costs. But so far, no one has put that ambitious project together.

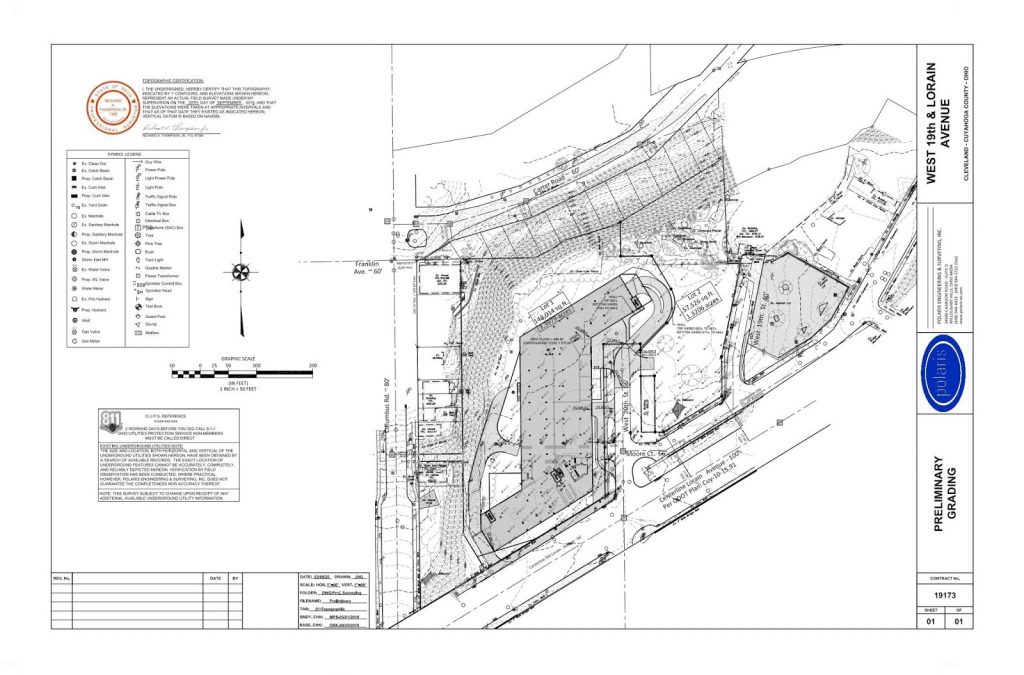

One that was rumored to be interested was Westlake-based Carnegie Management and Development Corp. But its attention instead turned to the other side of West 58th and acquired the 4.8-acre HKM Direct Market Communications Inc. property, 5501 Cass Ave.

According to an article in Crain’s Cleveland Business, Carnegie is making a long-term play here, possibly considering a mid- or high-rise residential development rising above the West Shoreway several years from now. To do so would require rezoning the site with either a form-based code or changing the height district to allow buildings taller than 35 feet.

Height districts along Detroit Avenue don’t increase from “two” (60 feet) to “three” (115 feet) until east of West 29th Street. That’s where Grammar Properties and Hemingway Development of Cleveland plus Cedar Street Development of Chicago joined forces to build Church+State, rising as tall as 11 stories with great views of the lake and downtown.

Some of the same players will build again, this time at a development called Bridgeworks on the northeast corner of West 25th Street and Detroit. From here all the way down to the Cuyaoga River, the height district is a lofty “five,” meaning buildings as tall as 250 feet can be built.

Although Bridgeworks isn’t likely to rise anywhere near that tall, another proposed development, this time on the north side of Superior Viaduct, intends to use every bit of the height limit. United Community Developers plans to build a 27-story apartment building called The Viaduct starting in mid-2021. It will have views of and access to both of Cleveland’s waterfronts — the lake and the river.

Just down the hill, along the West Bank of the Flats, more potentially vertical development is in the offing. Here, Columbus-based CASTO reportedly was seeking to acquire?5.6 acres of waterfront land. At $3 million per acre, the asking price would demand a large-scale, potentially high-rise development to offset the land acquisition costs. But CASTO and seller Jacobs Entertainment Inc. couldn’t finalize a deal. There are reportedly other interested parties, however.

|

| How might the Flats’ West Bank get developed in the near future is anyone’s guess. But it could follow this vision proposed recently for Jacobs Entertainment that is selling its riverfront land (AODK). |

Another development team, including Cleveland-based Paran Management, is interested in developing a riverfront property at 1250 Riverbed St., also reported only at NEOtrans. Sources say their residential development might also be a high-rise. According to recent reports, Paran and another developer are in conversations about building a shared parking garage on Elm Street the north side of the Superior Viaduct, as was previously noted in this May article as well as in this June article.

Yet another high-rise is in the works that could offer river and lake views, this time on the Flats East Bank. What is sometimes called Phase 3B (Phase 3A’s riverside restaurants/bars are under construction) would include a 12-story building featuring micro-unit apartments over commercial uses and possibly an adjoining theater.

Downtown has a growing number of high-rises, including 14 residential buildings of 15 stories or more. Nine of those residential towers were opened in the past decade either through new construction or by conversion of older commercial buildings.

More are coming, including the 23-story City Club Apartments at 720 Euclid Ave. It received final design approval by City Planning Commission last week and could see construction in November. Two more mostly residential high-rises are in the works, including a conversion of the historic 17-story Rockefeller Building as well as possibly a new-construction tower at the edge of the Warehouse District.

The last two would be spin-offs from the $300 million investment that Sherwin-Williams Corp. is making by building a new headquarters in downtown Cleveland. It’s main building on the west side of Public Square will reportedly rise to between 45-55 stories, potentially approaching the height of the city’s tallest — Key Tower.

More high-rise residential buildings might be built someday, just outside of downtown or along the lake. Near the East Shoreway and the Waterfront Line just northeast of downtown, buildings are limited by a “four” height district, maxing out at 175 feet. But south of the railroad tracks and the lake bluff and east to Interstate 90 is a “six” height district where buildings as tall as 600 feet could be built. East of there along the lakefront, 115 feet is the height limit.

The area northeast of downtown has no buildings of height nor are there any plans to construct any. That’s too bad, as downtown’s building heights drop off a cliff from the 20- to 40-story towers of the Erieview District west of East 12th Street to buildings of only a few stories east of there.

That could change depending on the outcome of new planning efforts underway by several public-sector entities: Cleveland State University (CSU), the Cleveland Metroparks and the Ohio Department of Transportation (ODOT).

As NEOtrans first reported in June, CSU is starting a new campus-wide masterplan. Among the facilities that CSU will reportedly look at is addressing a shortage of student housing. It may also focus on new efforts to dramatically increase its medical education offerings. It could even replace or renovate Rhodes Tower, CSU’s tallest building.

The Metroparks is conducting a land use plan for the lakefront east of Burke Lakefront Airport to Gordon Park. This is focused on recreational offerings and boosting public access to the lake from the neighborhoods to the south. A similar effort to improve access to Edgewater Park on the West Side helped boost real estate investment in areas south of the of the Shoreway (Interstate 90 here) and lakefront railroad tracks.

A similar outcome could occur on the East Side and create an “Edgewater East” as some real estate developers described it. Much of the area south of the lakefront railroad tracks is still industrial, but there is more developable land north of tracks on the East Side vs. the West Side. That’s especially true after FirstEnergy demolished its Lake Shore Power Station in 2017.

And that leads us to ODOT’s lakefront plans. It is looking at how to protect Interstate 90 from Lake Erie’s rising water levels and wave action. The highway is only a few feet from the lake at the location where the road went around the former power station.

ODOT will look at better protecting the highway at its current location or possibly rerouting away from the lake through the former FirstEnergy property. The city has urged FirstEnergy and ODOT to consider rerouting the highway with the power station no longer there. It could open up significantly more lakefront land to restore Gordon Park nearer its original, pre-highway size. And it could make land more accessible to residential development south of the highway.

Each of these public-sector planning efforts could foster more fertile sites for more lakefront high-rises east of downtown. They could help create more quality housing, boost retail offerings and improve lake access on the East Side. And it would create a more impressive entrance to Cleveland’s urban core on I-90 from the east — the kind that every big coastal city should have.

END

- Haslams announce Brook Park stadium-area development partner, updated plans

- Old Brooklyn structures OK’d for demolition

- Shoreway Tower has construction in view for 2025

- North Collinwood ‘historic’ modular townhomes OK’d

- Tick Tock Tavern closing after 75+ years

- Gordon Square development wins approval

Comments are closed.