Sometimes living in Cleveland is a walk in the park. And Census data shows more adults are choosing to live here as its economy is producing more output per capita than the average among 106 of America’s largest cities studied in a recent analysis. And Clevelanders’ wealth grew by $2.1 billion between 2017 and 2019 but dipped during the pandemic (KJP).

CLICK ON IMAGES TO ENLARGE THEM

In the simpler days of Census data, population numbers for a given metro area either went up or down in lockstep with that region’s economic output. There were few wrinkles in the data to pull apart and analyze. Now, there’s tons of data to grapple with, offering multiple story lines.

The local media has looked at several of those story lines. One of them is Greater Cleveland’s growing diversity and an increase in occupied housing units in the city of Cleveland, even though its population went down.

Here’s another story line — the city of Cleveland and Cuyahoga County are growing and shrinking at the same time.

Urban planning consultant Pete Saunders wrote for Bloomberg News a syndicated opinion piece titled “The ‘best places to live’ may not be the best places to live” noting that long-booming Sun Belt cities are running low on economic fuel. The subhead read “The link between the popularity of cities and economic growth has been severed. Some of the most vibrant metropolises in the U.S. are actually shedding people.”

Care to guess which urban areas he counted among the most economically vibrant – as measured by rates of per-capita Gross Domestic Product (GDP) growth above the national average – that were also losing population?

“Most surprisingly, a handful of Rust Belt metros — Chicago, Detroit, Cleveland and Pittsburgh, among others — outpaced the average per capita GDP gains yet actually lost population,” he wrote.

A minor correction — the five-county Cleveland metro area actually grew in population, adding 11,000 people over the past decade. As recently as 2019, the U.S. Census Bureau was estimating that Greater Cleveland would lose 25,000 people between 2010 and 2020.

How could Cleveland and Cuyahoga County be producing more economic output while still losing population?

Easy. Look at where we’re growing — and shrinking.

Cuyahoga County saw its 18-and-older population — aka the adult working population — grow 2 percent from 989,534 people in 2010 to 1,008,892 people in 2020. Yet, total population in the county fell 1.2 percent from 1,280,122 to 1,264,817.

The same thing likely happened in the city of Cleveland too, based on the increased number of occupied housing units but with a 6 percent decrease in population since 2010. Look at downtown, for example. When it comes to demand for apartments in Greater Cleveland, downtown was king. After a hiatus in 2020, downtown was back in power in 2021, accounting for one-third of all apartment demand in Greater Cleveland.

Joanna Ganning, associate dean and associate professor of urban planning at Cleveland State University, noted the growth-decline paradox in a recent tweet. She said the number of households in the city increased 6.3 percent just in the six most recent years of available data, from 2012-18, even as population fell.

“So much subtext to those simple stats,” she wrote.

One takeaway of course is there’s been a decrease in household size — a trend that’s been continuing in the USA for hundreds of years. And it has taken a sharper turn since our parents and grandparents were raising families of three, four, five or more children per household. Not anymore. In 2010, 77.3 percent of Cuyahoga County residents were 18 years and older. Last, year that number jumped to 79.8 percent.

Increasingly, Americans aren’t getting married until later in life and we aren’t having as many kids as our parents or grandparents did. In fact, we aren’t having enough babies to replace deaths of older Americans. The only reason why America is gaining population anymore is because of immigration.

One reason why Cleveland and Cuyahoga County aren’t growing in population is because they aren’t attracting families and immigrants like they did decades ago. But they are still becoming more diverse. Cuyahoga County’s number of Latinos more than tripled, the multi-racial population nearly tripled and the population of Asians grew by one-third, according to a recent report.

Census data also shows a new phenomenon — the number of white people increased in Cleveland, now comprising nearly 40 percent of the city’s population, up from 37 percent. Meanwhile, the black population dropped, falling from 53 percent of the city’s share to below 49 percent. Latino residents grew from 10 percent to just shy of 12 percent of Cleveland’s population.

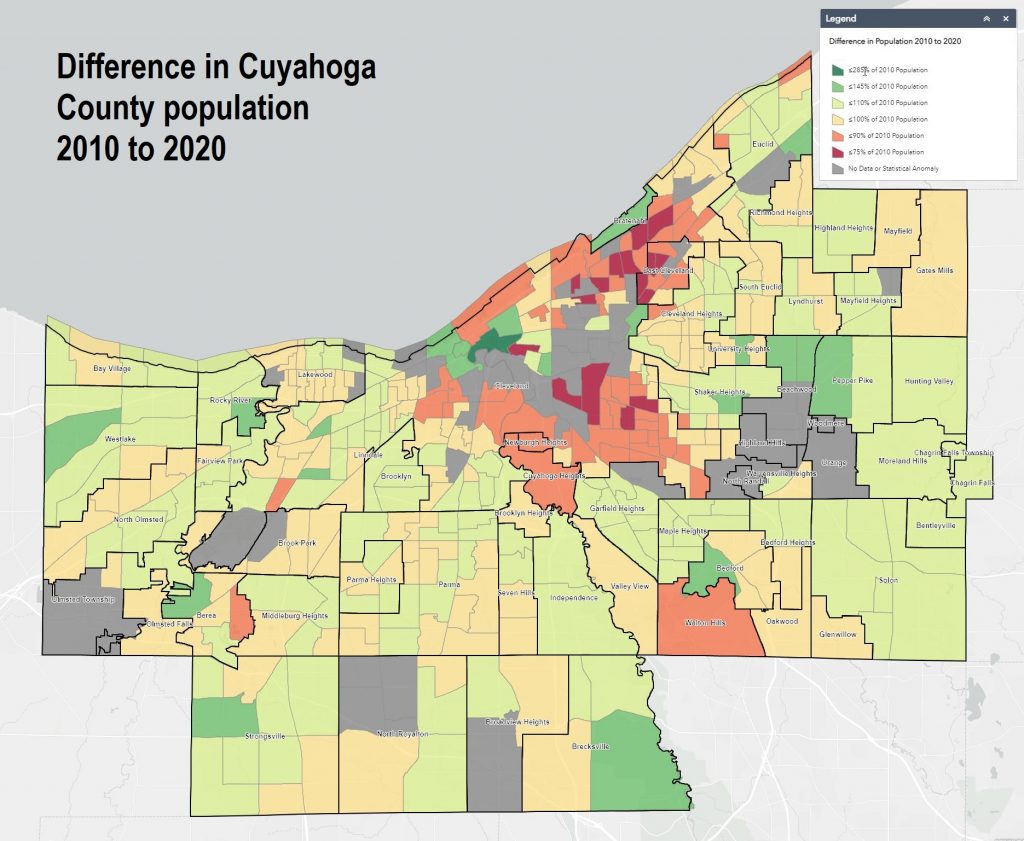

Those are reflective of Cleveland in general — where it was the best and worst of times. No city in Cuyahoga County saw census tracts with more growth and decline than those in Cleveland. In and near downtown, population grew 45 to 185 percent in eight Census tracts since 2010. There were only 13 other Census tracts in the rest of the entire county achieving such population increases of more than 45 percent.

At the same time, there were 12 Census tracts in Cleveland that lost 25 percent of more their population since 2010. All of them were on the city’s East Side. In the suburbs — actually only one suburb, East Cleveland — had any Census tracts losing 25 percent or more of their population. That city had four of those big-loser tracts.

While the percentage of black residents dropped in Cleveland, it increased in 28 out of 37 municipalities in Cuyahoga County. The data strongly suggests black people, probably with children, moved out of Cleveland — especially from the troubled East Side — and moved to the suburbs or elsewhere.

As for Cleveland’s average GDP gains per capita, Saunders noted that Rust Belt cities have stopped focusing on saving their old-school manufacturing jobs and instead are diversifying their economies. In the 1950s, shortly after Cleveland’s population peaked, one-third of its jobs were in manufacturing. Now it’s just 11 percent.

Since then, Cleveland and other cities are “investing in knowledge sectors such as tech, finance, and ‘eds and meds’ to match today’s economic landscape. That’s led to productivity gains even without adding more people,” Saunders wrote.

Today, the eds and meds sector comprises 20 percent of Cleveland’s employment. The epicenter of that sector is in and near Cleveland’s University Circle. There, developers are estimating that there’s a demand for up to 10,000 housing units in the next 5-10 years that would require at least several dozen large apartment buildings plus hundreds of townhomes to satisfy that demand.

And while lower-income and working-class families are moving out of Cleveland, they appear to be replaced by professional singles and couples. Those middle- to upper-class arrivals are usually without children, as noted in this NEOtrans analysis from late-2019. This gentrification is reflected in city income tax data.

Even before a 2016 income tax rate increase, Cleveland was getting wealthier from the back-to-the-city movement. It continued unabated until the start of the pandemic in early 2020. For people living and working in Cleveland, their wealth grew by $2.1 billion, or 13.6 percent from the start of 2017 to the end of 2019, based on city of Cleveland income tax collections.

City of Cleveland income tax revenues grew from $389 million in 2017 to nearly $442 million in 2019. It dropped in 2020 to $410 million due to the pandemic. Revenues aren’t expected to recover to pre-pandemic levels until 2023, according to conservative city estimates. Even last year’s numbers, albeit unaudited, were far higher than 2017’s.

So while Cleveland and other large, affordable Rust Belt cities were diversifying their economies with wealthier economic activities, Saunders said popular Sun Belt cities like Orlando, Tampa/St. Petersburg, Dallas, Las Vegas and Phoenix saw their average per capita GDP gains rise less than the overall average for the 106 largest metros he studied.

“The places we’ve traditionally thought of as ‘winners’ — the big coastal cities (New York, Los Angeles, etc) and Sun Belt metros — may soon face problems,” Saunders wrote. “The former are rapidly becoming unaffordable and driving out middle-class families. The latter could suffer from a glut of under-skilled workers in an environment that increasingly demands high-skilled labor.”

By contrast, he said Cleveland and other cities in the middle of the country are beginning to generate real economic opportunity while remaining affordable and livable, he said. Cities like Buffalo and Cincinnati saw their first population gains since 1950.

Cleveland, while losing population overall, saw a moral victory in the growth of its working population. And its better-than-average growth in GDP per capita is real and important, even though it won’t be captured in Census data. It could be just what’s needed to draw more new arrivals seeking a high quality of life at an affordable price.

“If they (Rust Belt metros) haven’t started drawing new residents yet, they will soon,” Saunders said.

END

- Michael Symon joins River Roots’ move to Flats

- Tenant ID’d for big new industrial development near Hopkins airport

- $119M Lakewood Common project goes vertical

- CWRU to renovate, expand one of its most historic buildings

- Master Chrome coming down, cleaning up

- Familiar Ohio City buildings go on sale for the first time in 143 years

Comments are closed.