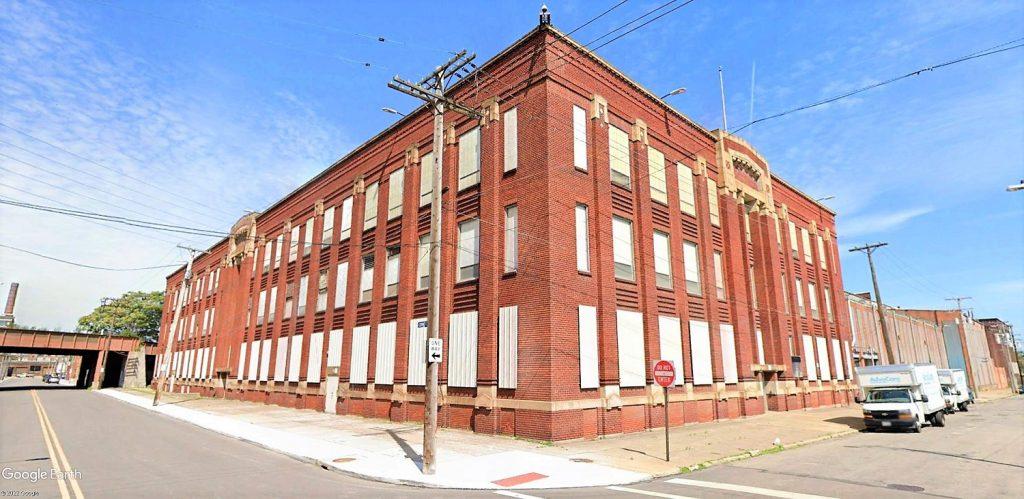

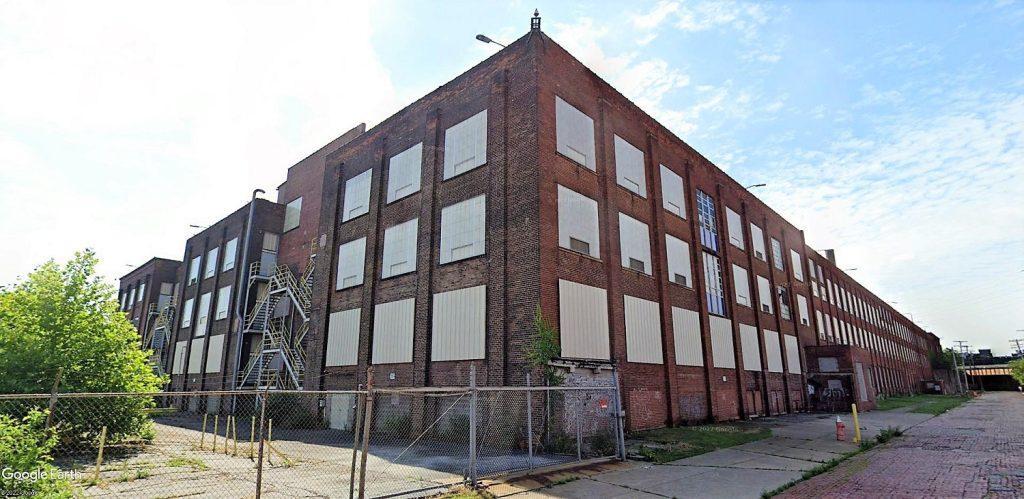

This substantial building at the corner of East 45th Street and Commerce Avenue, plus all of the structures in the background, are proposed to be demolished. They comprise the former General Electric Euclid Lamp Plant whose origins go back to 1880 when its first buildings were constructed for the Brush Electric Company (Google). CLICK IMAGES TO ENLARGE THEM

GE claims buildings are too polluted to save

A sprawling factory complex on Cleveland’s near-East Side that incubated many lighting, industrial and transportation innovations is proposed to be demolished by its owner of the last 130 years, General Electric (GE). The Design Review Committee of Cleveland’s City Planning Commission has scheduled a presentation this week by GE’s engineering consultant Stantec on why it should approve demolition of the factory, called the Euclid Lamp Plant, 1814 E. 45th St. But not everyone agrees the factory has to be razed before the property can be sold by GE.

The history of GE’s Euclid Lamp Plant goes back to before GE’s ownership. It traces back to 1879 when Cleveland inventor and industrialist Charles Brush placed 12 electric-arc lamps on downtown’s Public Square and made Cleveland the first city in the USA to have electric street lights. Each one of Brush’s carbon arc lamps had the intensity of 4,000 candles and was said to turn night into day. They apparently were brighter than those which illuminated Paris a year earlier, and was the first city in the world to have electric streetlights.

The year 1879 was also when Thomas Edison invented the incandescent electric light bulb for use indoors. Brush’s feat was no less of a sensation around the world and it won for him business from many cities. It led to the sudden growth of the Brush Electric Co. and the construction in 1880 of a 200,000-square-foot lighting plant at the corner of Mason Street (now Commerce Avenue) and Belden Street (today’s East 45th) with McHenry Street (now East 43rd Street) forming the new factory’s western boundary.

Even though a GE predecessor bought the plant in 1889, some Clevelanders still called the plant “Brush Electric” more than a century later. The plant was the first home of a research consortium called the National Electric Lamp Association (NELA) in 1901, before GE relocated it to the headquarters for its lighting division in East Cleveland a dozen years later, called Nela Park.

The Euclid Lamp Plant was closed by GE in 2008 — a victim of global economics and a shift in technology. For years, GE had been shipping good-paying American jobs overseas to countries with cheap labor and fewer environmental regulations, namely China and Hungary. And the technology shift was from 19th-century incandescent light bulbs to spiral-shaped compact fluorescent lamps or CFLs. The cost to retrofit the Euclid Lamp Plant to make CFLs was estimated at $40 million and yet it still wouldn’t be able to compete with cheap overseas labor.

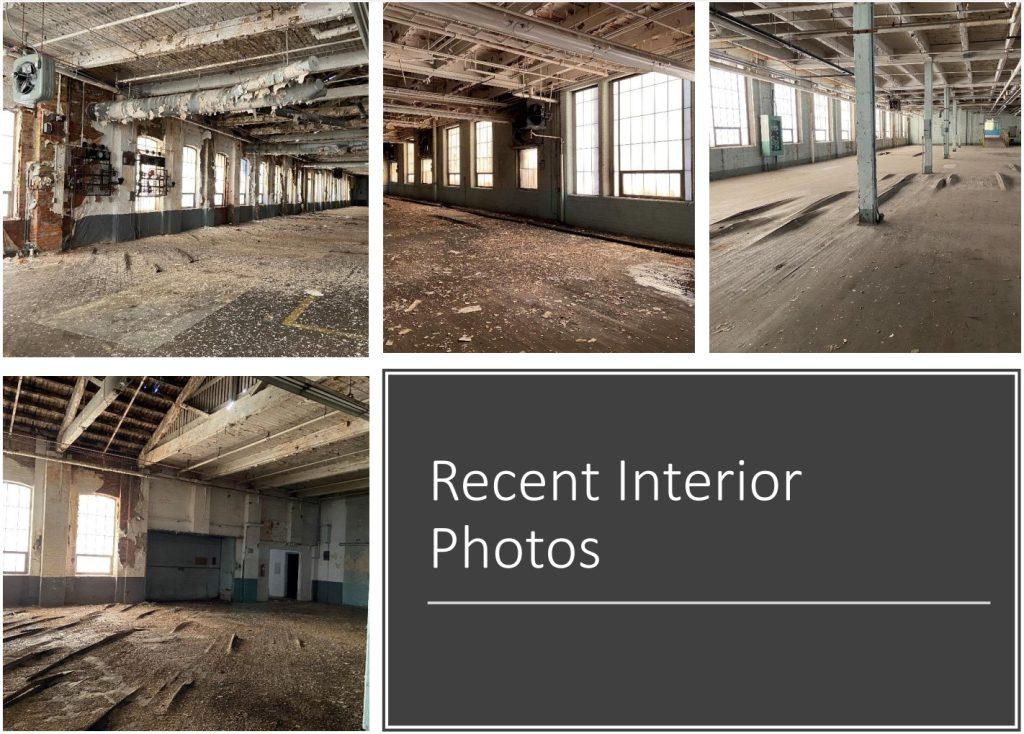

The plant has sat vacant ever since with all of its windows and doors covered over. The 16 interconnected brick-and-mortar buildings with wood floors appear to be in good structural condition despite that the newest buildings on the site were built in 1920. Those additions expanded the factory to 423,000 square feet. Other structures date back to when Brush first opened the plant 142 years ago.

NEOtrans secured a copy of Stantec’s presentation to the city, requesting the factory’s demolition. It acknowledges that “the buildings are generally structurally sound with localized structural issues due to roof leaks and lack of climate control.” Those issues include rotted and buckled floors, flaking paint and deteriorating asbestos, Stantec’s report said.

“During incandescent bulb manufacturing, certain bulb-making machines contained several 1-liter mercury reservoirs that were used to create a vacuum within the bulbs,” the report continued. “Other machines relied on large mercury vacuum pumps that operated across the facility similarly to evacuate the bulbs. Mercury releases were common throughout the buildings from both types of machines. These releases caused elemental mercury to be present in many building locations between wood floor layers and in floor drains.

In the center of the former Brush Electric plant is a yard where Edward Bentley and Walter Knight in 1883 built and tested what would become America’s first commercial electric railway. And in a corner of this factory in 1898, Alexander Winton built the first commercially manufactured automobile (Stantec).

“GE has determined that it is not feasible fully to remove all of this elemental mercury from the buildings without demolishing building infrastructure. Despite several attempts at non-destructive mercury removal, mercury vapor assessments in the building continue to detect mercury vapor at concentrations that exceed standards for residential and commercial uses according to guidance from the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry.

“GE’s experience at similar facilities confirms that mercury remediation without demolition is infeasible. In several cases after the passage of many years, GE has had to step in to demolish similar mercury-impacted facilities that had been sold and redeveloped. GE is unwilling to risk a similar outcome in this case. Other environmental building issues include the presence of asbestos, lead-based paint, and metals-impacted dusts,” Stantec’s report concluded.

But Steve McQuillin, an historic preservation consultant, said that there are ways of safely renovating structures that were contaminated with mercury. He worked with GE when its lighting division was headquartered at Nela Park in East Cleveland and continues to work with the new owners of the facility. In March of this year, GE Lighting sold Nela Park to Phoenix Investors, an affiliate of a Milwaukee-based real estate firm. GE Lighting was acquired by Savant Systems Inc. in 2020. Savant has maintained partial tenancy at Nela Park after Phoenix’s acquisition.

“Back in the late 1980s I started working as a preservation consultant to GE Lighting at Nela Park,” he said. “The first tax-credit project was the rehabilitation of Cuyahoga Lamp Building 328. That supposedly had mercury contamination due to the lamp-making process. It was solved there by encapsulation, adding a subfloor over the original. That would seem possible here (at the Euclid Lamp Plant) as well.”

At the corner of Commerce Avenue and East 43rd Street, the Euclid Lamp Plant comes within feet of the former Cleveland & Pittsburgh Railroad (built in 1852 and elevated 59 years later), now Norfolk Southern. Concrete supports remain from an elevated railroad siding that was built in 1911 to serve the lighting plant (Google).

Cuyahoga Lamp Building 328 measures 107,951 square feet and currently has Savant as its primary tenant. It is one of 20 buildings totaling 1 million square feet that are available for lease at Nela Park, according to a brochure published by Phoenix Investors and made available on the real estate listings site LoopNet. Cuyahoga Lamp Building 328 fronts Noble Road and is to the right of Nela Park’s main entrance. There are no plans to demolish it or other buildings at Nela Park.

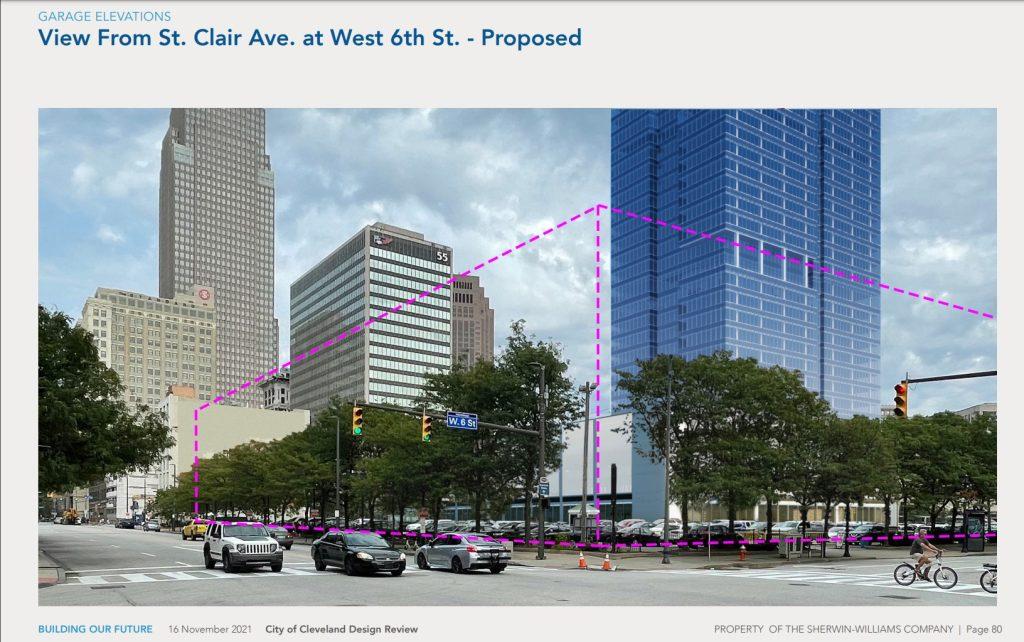

GE said it would demolish all buildings at the Euclid Lamp Plant, remove all foundations, fill building footprints with gravel and retain existing asphalt coverings left from the factory. A fence would be placed around the perimeter of the site and the property put up for sale. The site measures 7.1 acres. Stantec says that air, water and land at the property, outside the buildings, have been thoroughly sampled and did not identify any environmental concerns that would interfere with the vacated property’s reuse.

Richard Barga, managing director of Cleveland MidTown Inc., a community development corporation, said the CDC is meeting with GE representatives this week about their plans to demolish the factory. Thus he did not have any comment at this time.

The scale of the Euclid Lamp Plant, still referred to as Brush Electric by some of Cleveland’s more senior citizens, is best appreciated along the East 43rd Street side of the property. East 43rd is also one of two brick streets remaining in the immediate area with East 41st Street being the other (Google).

McQuillin would not comment on whether GE was primarily concerned with being sued by a future user of any of the Euclid Lamp Plant’s buildings, if one or more them was preserved and repurposed. However, he said the buildings appeared to be in good condition and potentially suitable for reuse as commercial, residential or live-work lofts, similar to other former industrial buildings in Cleveland.

A spokeswoman for The Cleveland Restoration Society was more cautious. She said they had not undertaken any feasibility studies or seen any studies by others to determine the feasibility of preserving and restoring the Euclid Lamp Plant for new uses.

“From a quick visual inspection it certainly has integrity to be considered for (a preservation) designation,” said Margaret Lann, director of preservation services at the Cleveland Restoration Society. “But I understand that there’s also challenges with the mercury and moving forward with that probably depends on how much hazardous material there is. From an historic standpoint it certainly would be (eligible for designation) as it retains its (architectural) significance. It could be a local landmark and make a great adaptive reuse. But commenting on how much is feasible (to redevelop) is outside of what we know at this time.”

In its early years, Brush Electric hosted entrepreneurs seeking to make their mark on the world. In 1883, two of the factory’s most notable guests were Edward Bentley and Walter Knight. On the shop floor they built electric motors, conduits and other equipment, and in the factory yards outside they laid a common railway track but with an electrical conduit between the rails. Along it they tested a streetcar but without a horse pulling it. Instead, an electric motor with a plow-like extension collected the electricity from the conduit. That ultimately led to the electrification of a one-mile stretch of the East Cleveland Street Railway which became America’s first commercial electric railway. Their system was adopted by multiple cities in the late-19th century.

Eleven years after Charles Brush illuminated Public Square with man-made electricity, the first time a U.S. city street had been illuminated with electric lights, this replica of Brush’s electric arc lamp was built into Cleveland’s first skyscraper — the 1890-built Society For Savings Building. This was the scene in 1965 (Library of Congress).

In addition to making headlights and other lighting for cars, the Euclid Lamp Plant has another link to the automobile industry. The first commercially manufactured automobile was built in a corner of the factory in 1898, in space rented by Alexander Winton, for his Winton Motor Carriage Company. There, the company was incubated until it was making dozens of cars per week by hand. The company relocated four years later to a new factory that still stands at 10601 Berea Rd. on the city’s west side. Winton was one of the world’s largest automakers in the 1910s until Ford’s assembly line made its cars more affordable. Winton continued to make truck engines under General Motors’ ownership.

A decade after Brush illuminated an American city’s streets with electricity for the first time, his feat was still fresh in people’s minds. So a Brush arc-lamp set in decorative wrought-iron was installed on the corner of the city’s first skyscraper — the Society for Savings Building on Public Square — where it remains today. Brush was responsible for 50 patents in his career, including predecessors of the modern electric generator and the modern wind turbine.

Brush Electric was acquired in 1889 by the Thomson Houston Electric Co. which merged two years later with the Edison General Electric Co. to become GE. The East 45th plant also became the home of NELA in 1901 to support and share among member companies research and development into better lighting technologies, according to the Encylopedia of Cleveland History.

GE owned 75 percent of NELA and moved the headquarters of its lighting division in 1913 to Nela Park in East Cleveland, considered by some to be the nation’s first industrial park. But the Euclid Lamp Plant continued to be the region’s largest lighting manufacturing facility, despite the opening of other plants later on at East 152nd Street in East Cleveland, plus in Austintown, Conneaut, Niles, Ravenna and Willoughby.

In 1980, 650 people worked at the Euclid Lamp Plant, more than at any of the other GE plants in the area. But by then, the region’s lighting industry was already in decline. During the 1970s, GE closed three of its facilities in Greater Cleveland as America began to deindustrialize and ship more jobs overseas. More layoffs came, reducing the staffing at its Northeast Ohio lighting plants to just 425 people total — 125 of them at the Euclid Lamp Plant, making incandescent and halogen bulbs, according to media reports.

END

- Cleveland, Bedrock seek $1 billion for riverfront development

- CRE industry lauds Bibb’s construction permit overhaul

- Bridgeworks design evolves again – minus hotel

- Cleveland Kitchen wins $10M in tax credits

- Welleon gets an ‘A’ in testing Cleveland’s market

- EPA gives Greater Cleveland $129.4M for five solar arrays, reforestation