Although University Circle is Greater Cleveland’s fastest growing employment district and one of its fastest growing residential areas, its transit offerings haven’t changed much in decades. The HealthLine offers less frequent and slower buses than before 2008 and has only one rail line which skirts the district (NEOtrans). CLICK IMAGES TO ENLARGE THEM.

50-year-old agency may cut itself to irrelevance

A COMMENTARY

If the Greater Cleveland Regional Transit Authority (GCRTA) was a human being, it might look like the Black Knight from the 1975 movie “Monty Python and The Holy Grail” after being confronted by King Arthur. In the British comedy, the king had hacked off the knight’s arms and legs, yet the knight continued to fight, claiming “It’s just a flesh wound.”

But the difference in reality is that GCRTA isn’t fighting back. The reason? It’s GCRTA doing the amputations of itself in the face of attacks by depopulation, deindustrialization, urban sprawl, and loss of downtown employment, to name a few.

GCRTA appears to be in desperate need of structural changes, long overdue in this 50th anniversary year. But the creation of fact-finding panels or even board-level discussions aren’t happening to consider those changes. Yet.

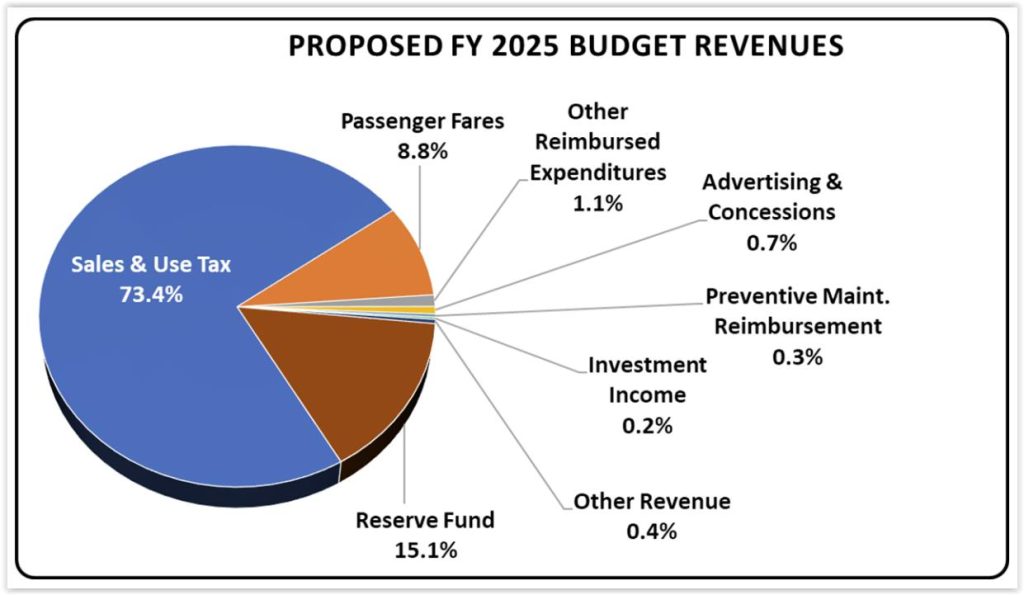

Instead, the transit agency seems ready to prune itself again in the face of those threats, as its primary source of funding, the 1 percent countywide sales and use tax, has seen its revenues plunge over the decades.

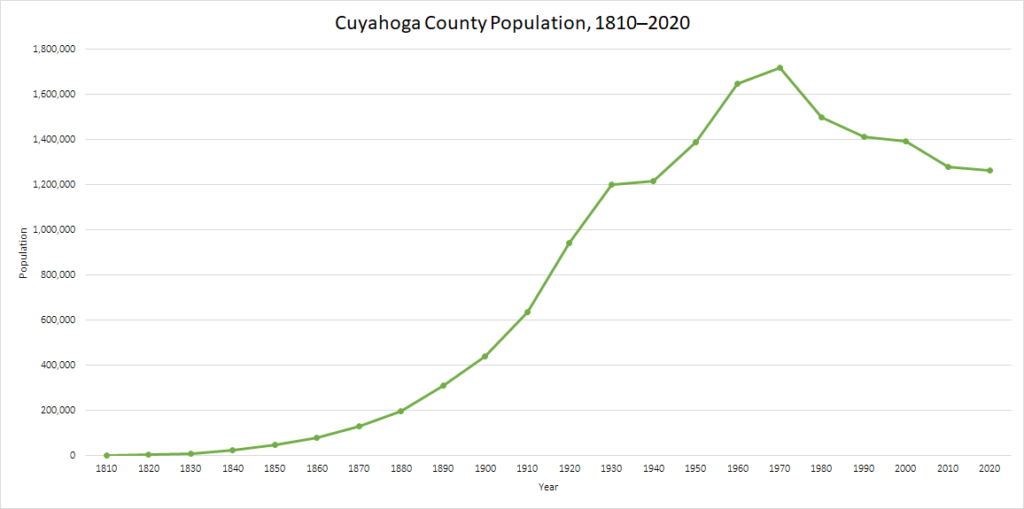

GCRTA and its sales tax were established in 1975 when the last census data point, from 1970, showed Cuyahoga County’s population at its peak of 1.72 million people. Cuyahoga County had never lost population in any decade going back to its founding in 1807.

An ongoing, sustainable subsidy was sought to reduce fares which, for much of GCRTA’s history, covered less than one-fourth of the cost of public transportation. Today, it’s less than 10 percent.

The sales tax was chosen as GCRTA’s subsidy because it was assumed that sales tax revenues would keep rising with Cuyahoga County’s population. Instead, population has fallen every decade since then, to 1.26 million in 2020.

The sales tax has fallen ever since then, too — until recently. Like the county’s population, and even the City of Cleveland’s, the decades-long decline in revenues has virtually stopped. But that’s still of little help to a transit agency where inflation continues to eat into budgets.

And among transportation and infrastructure-related organizations, their inflationary costs grew much higher than in the rest of the economy due to supply chain issues, labor shortages and higher energy costs. Steady inflationary growth of 3-4 percent in the 2010s has given way to shocking double-digit increases in the 2020s.

Speaking of shocking, GCRTA this year experienced a sudden 34 percent spike in employee healthcare and prescription costs to more than $45 million, representing a big bite out of the authority’s $365 million budget. The average annual healthcare increase over the prior six years was 3.8 percent.

All those cost increases mean that GCRTA’s $55 million funding reserve with which it started 2025 is likely to be gone before the end of 2026. After that, the only place GCRTA can go to protect its budget is to cut — jobs, frequency of services, and possibly even entire routes. Or so GCRTA believes.

For some of the veterans at GCRTA, many of which are in top managerial positions, their experience with Cleveland and Cuyahoga County is that of decline. That’s all that they have known. Over decades, a victim mentality has been ingrained in them.

So is the notion of cutting GCRTA services in the face of that decline. It does make sense. If your population is declining, it seems reasonable that the amount of service you offer should diminish as well.

But transportation is different. It need not be a victim. It can be a solution to reversing negative economic forces if properly engaged as more than just a social safety net.

The mere presence of transportation can induce economic growth, not just react to it. Ports, canals, railroads, roads, aviation and, yes, transit can accelerate commerce while reducing the cost of it. When transit-friendly zoning, financial incentives and programs exist to aid it, transit draws more economic activity.

The 512,000-square-foot, mixed-use Intro development next to the Ohio City Red Line station had its origins in a thought exercise by GCRTA staff. They proposed demolishing an existing, suburban-style strip shopping center with a large, multi-story development to stir developer interest in the site (NEOtrans).

Investing in public transportation and transit-oriented development (TOD) makes a city more marketable to two groups of people who were and are responsible for innovation, new businesses and population growth in American cities — immigrants and young adults.

Today, with remote working, that’s even more true. I can manage this blog from anywhere on Earth that has WiFi. Increasing numbers of people and their jobs are also similarly unconstrained.

Cleveland’s ability to market itself as a low-cost city to live-work-play is hurt by its car dependency — the second-largest personal expense after housing. More housing, jobs, shopping and services near transit offer a low-mileage, low-cost lifestyle which Cleveland can market to the world.

Adding more housing and jobs within a comfortable walking distance of high-frequency transit also offers ladders of success to reduce poverty among Greater Cleveland’s existing populations. But not if you’re continually cutting service.

To its credit, GCRTA created its first TOD reserve fund to aid TOD projects, but it did so only last month. TOD is a long-term, structural revenue additive to transit agencies although it takes a long time to add enough of it to make a difference to the bottom line.

Sadly, GCRTA has extended that timeline by being slow to embrace it. In a defeatist mindset, some at GCRTA claim it’s because Cleveland isn’t growing. That’s only partly true.

Cleveland saw a record $3.11 billion in commercial construction permits issued in 2024, nearly doubling 2023’s total. TOD activity also reached a record high in 2024 in Cuyahoga County, although 92 percent of it happened in the City of Cleveland.

In University Circle, one of Ohio’s fastest growing and vibrant job centers, GCRTA routes and service levels are relatively unchanged in the past 20 years. If anything, there’s less of it.

And if the budget cutters get their way in the coming months as the best way to address GCRTA’s financial woes, the transit agency will make itself even less relevant as Cleveland Clinic cringes in dropping $100 million for the next 1-million-square-foot parking garage.

Service cuts will stunt city efforts to redevelop The TOD Zone — land located within a 5-minute walk of a high-frequency transit stop offering a bus or train every 15 minutes or better.

The Cleveland Planning Commission reports that over 200,000 jobs and nearly half of the city’s total population are in The TOD Zone. This zone has 78 percent of the city’s jobs but only 23 percent of its housing.

There are 17,000 vacant lots totaling over 2,800 acres in this footprint. There are also hundreds of acres of parking lots. GCRTA controls nearly 80 acres of that next to stations which should be made available to investors and developers, with conditions on ensuring transit access, customer parking and transit-friendly land use, via requests for proposals.

But that’s a long-term answer to a long-standing problem that has to be addressed immediately. There are no easy answers in the short term. In the past, raising fares hasn’t generated revenues. It merely discouraged ridership. GCRTA says it is not considering a fare increase.

To save money without service cuts, the City of Cleveland and GCRTA should work together to identify new revenue sources that can be implemented in the short term.

One is to ensure all city employees are enrolled in GCRTA’s Commuter Advantage program. Same for all downtown employers as is done in Columbus. Both can supply an immediate cash infusion.

Starting next year, GCRTA will begin taking delivery of its first new trains in 40 years. It will also have a potential public relations bonanza at which time the public will want to capitalize on the ability of these new trains to travel on any route, and possibly some new ones that could offer stakeholders more economic development opportunities (Siemens).

Another near-term option that was suggested by Mayor Justin Bibb was to tap Cleveland’s $100,000 to $150,000 per month in smart parking meter revenue. But city officials are now proposing using the added revenues to fund more street lighting, crosswalks and speed tables to improve pedestrian safety.

Yet another is redirecting $15 million in city funds allocated for annual maintenance of Huntington Bank Field. But that option likely won’t be available until after the Cleveland Browns leave for Brook Park in 2029.

Clevelanders for Public Transit has urged closing the $19 million-per-year GCRTA police department and replacing its 128 full-time officers with ambassadors who ride the buses and trains. Downtown Cleveland Inc. pays $4 million per year to Block by Block Inc. to run its 50-person Clean and Safe ambassador program.

The advocacy group also has urged increasing the county sales tax by a one-half of a percent. But that’s a tough sell if it’s only to maintain the status quo.

Instead, use it to expand service. The perfect time to seek this is in 2027 when GCRTA rolls out the first trains in its $450 million order of new railcars. These are GCRTA’s first new trains in more than four decades. It is a significant public relations opportunity.

GCRTA buses go slow by design to keep buses on schedule and to provide more jobs to drivers. But there’s a lot of fat in the budget that could be eliminated by tightening up bus schedules — especially with the long-awaited introduction of contactless fare payment and giving buses and light-rail trains signal prioritization at intersections (NEOtrans).

GCRTA can market this sales tax hike as allowing it to maximize the potential usage of its new trains which will be able to operate on any rail line. In addition to adding several bus rapid routes, two new rail extensions should be sought — completion of the Waterfront Line as a Downtown Loop and a rerouting of the Blue Line from Shaker Square to Cleveland Clinic.

There are operational savings to be had, too, according to GCRTA insiders. The agency spends a lot of money to pay its drivers to go slow or be stopped, they said.

Bus schedules are not as aggressive as they could be, and slower service requires more buses and drivers. They can be sped up with more aggressive schedules aided by new policies and capital investment.

Regular bus, bus rapid transit and light-rail services are slowed by GCRTA’s reliance on cash fares. Slow boarding and waiting for passengers to pay fares are one of the biggest sources of vehicle stoppage times.

Its ever-elusive contactless smart card fare system has been talked about for years and was finally approved in March but has yet roll out. Technology installations started last month. There is no first start date yet. That’s one operational goal.

Traffic signals are also another cause of slow travel for transit vehicles. On high-frequency bus routes and light-rail lines, transit vehicles should be able to preempt traffic signals in the same way emergency vehicles do.

One problem is that GCRTA vehicles lack the transponders to trigger traffic signals to be all-red in all directions as they approach and pass. Another is that not all Cuyahoga County communities have the same signal pre-emption system.

Standardizing it would support mutual aid emergency services, not just improve transit services that reduce operating costs and grow revenues. Cumulatively, faster passenger boarding and signal preemption will save hours per day per high-frequency route. Faster transit service is more attractive to more riders.

There are options for GCRTA to save money that don’t involve cutting services. But GCRTA isn’t going to find them if it doesn’t look for them. Start by organizing a fact-finding panel with the realization that long-term structural changes may be needed on top of near-term efficiencies.

You’re not the victim, unless you want to be. And you’re not the solution either, if you don’t want to be. The difference is that being a victim finds you without any effort.

END