Safety, not development, drives demo

A row of buildings along Columbus Road in the Flats is due to be razed in the coming weeks by an active, local real estate developer. But there is no plan to replace buildings, including two from the 19th century that stand in a nationally registered historic district. Instead, according to a partner at the property’s owner, Integrity Realty Group (IRG) of Beachwood, the contiguous buildings would be demolished to keep them from falling down on innocent passersby. No structural analysis was included in the owner’s demolition requests to the city.

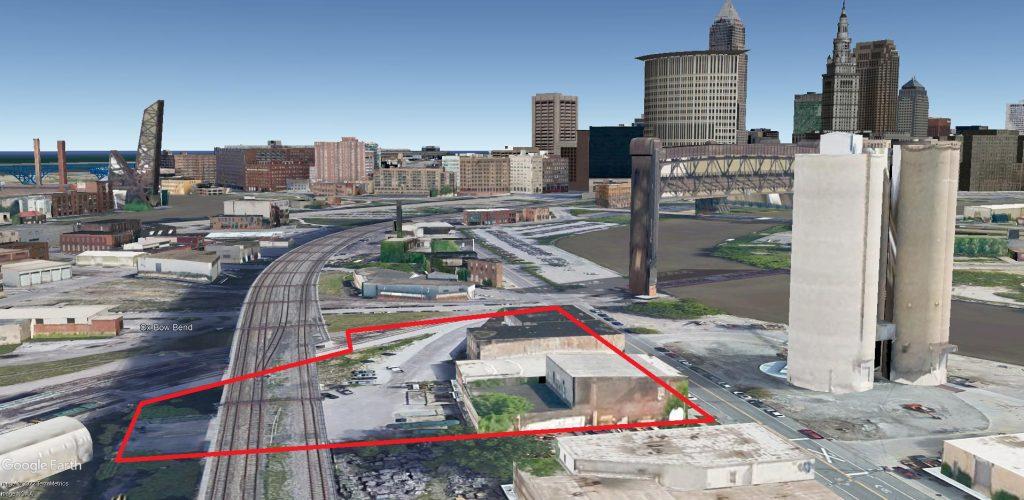

The three buildings are located at 1772-1800 Columbus and were acquired by IRG in early 2021 for $650,000, according to Cuyahoga County property records. That also included vacant land below the Cuyahoga Viaduct that’s owned and used by the Greater Cleveland Regional Transit Authority for its Red Line rail rapid transit. Then, in May of this year, IRG bought a triangle-shaped parcel measuring only 0.078 acres from Flats Industrial Railroad for $70,000. That increased the site’s total size to about 1.6 acres, which is identical to the developable area for the proposed 15-story Bridgeworks apartments and hotel over retail nearby at Superior Viaduct and West 25th Street.

Last week, IRG’s demolition contractor Terence R. Wilson, doing business as TRW Construction, LLC of Richfield, submitted applications to the city to raze three buildings — 1772, 1790 and 1800 Columbus Rd. Estimated cost for the demolition work according to the applications is $24,000. That includes removing all foundations, discontinuing and capping utilities, hauling away debris and backfilling the building sites with clean fill. The owner contact listed on the applications was IRG Partner Richard Brown.

“We are taking down buildings for safety reasons,” Brown said in an e-mail exchange with NEOtrans. “We have no current plans for the land due to the high interest rate and elevated material / labor cost environment.”

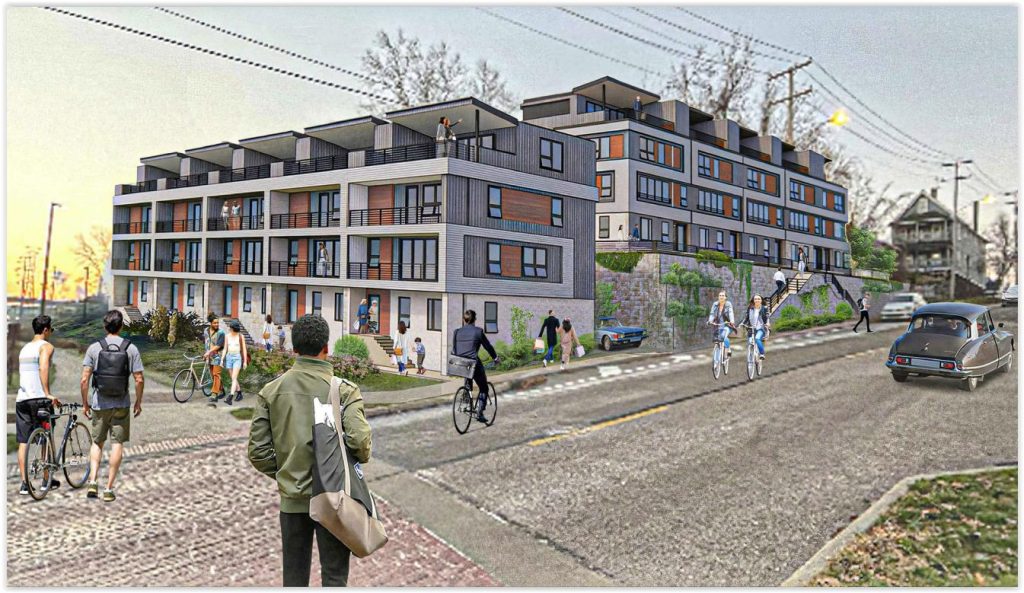

This development site is not to be confused with another one proposed nearby called The Pine, announced in March by Reallife Real Estate Group of Cleveland. That 0.42-acre site is at 1720-1736 Columbus. It involves a mix of renovating two mid-19th century buildings, demolishing another and adding new construction to offer 45 mostly one-bedroom market-rate apartments. Unfortunately, there’s been no visible progress on the project since its announcement. This project, like IRG’s property, is located in a federal Opportunity Zone, making it eligible for preferential tax incentives to attract private financing.

According to signs on IRG’s buildings and tenant Web sites, the buildings have or recently had as tenants a Cleveland Metroparks’ service center, Argonaut, a nonprofit organization providing marine training and safety to underprivileged youths, and the offices of the now-defunct Lolly The Trolley. The latter provided guided tours and charter trips around town for 37 years until it closed its doors in May. Jim Haviland, executive director of Flats Forward, a community development corporation, said he was not aware of any plans by the owner to do anything with the site after the demolitions.

“I was working with the developer last year, but I understand the plan has changed,” Haviland said. “We were aware of the demolition plans and have worked with the tenants on their relocation.”

Typically the city likes to see at least a conceptual plan for the future use of a property after its buildings are demolished, but no such plans were attached to their permit applications and the city’s chief building official Tom Vanover said none was submitted. A post-demolition site plan may be required when the buildings are located in an historic district as are IRG’s structures. In 2014, the National Park Service registered the entire Columbus Road Peninsula as a federally designated historic landmark district called Cleveland Centre. It isn’t clear who built the three endangered buildings or when.

“Nothing historic about those structures, which are on the verge of falling down,” Brown said.

Although he said he wasn’t familiar with the buildings’ internal structural conditions, historic preservation consultant Steven McQuillin disputed the assertion that the buildings aren’t historic. However, since the district was designated as historic but not these specific buildings, he said that doesn’t necessarily provide them with protections from demolition.

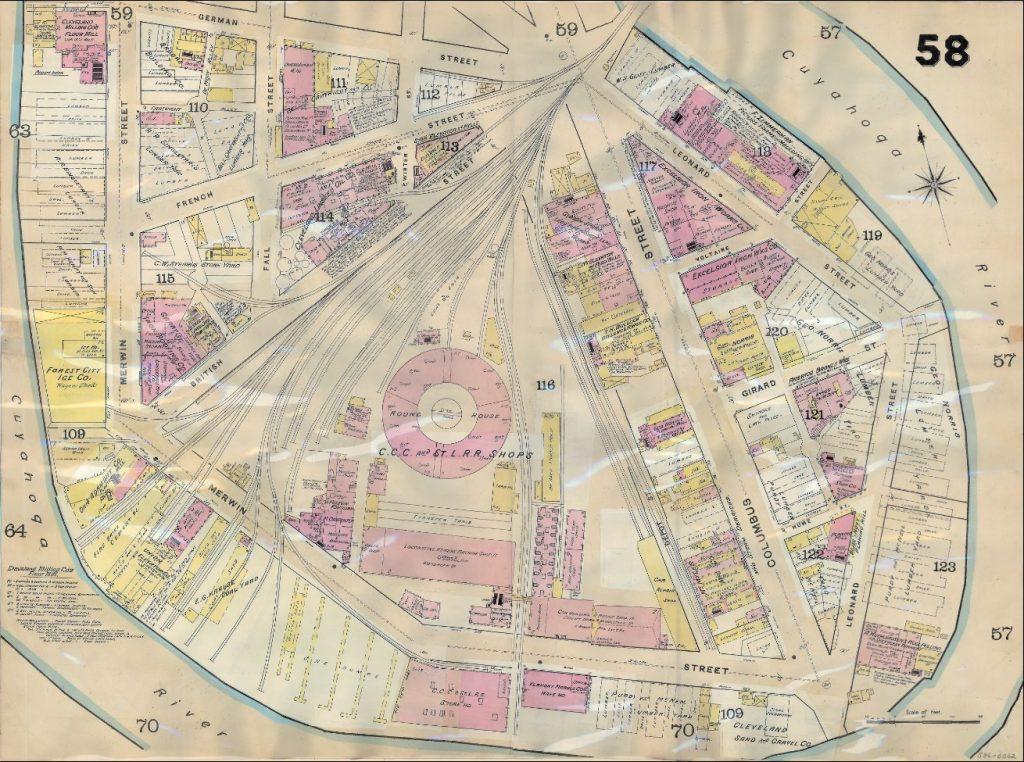

He said 50 acres on the Columbus Road peninsula were proposed to be developed starting in 1833 as an international trading and commercial district to capitalize on the 1825 opening of the Ohio & Erie Canal, which is why it was originally laid out with street names like British, French, German, China and Russia radiating outward like spokes on a wheel from a market center called Gravity Place. The buildings to be demolished are near Gravity Place.

“There’s a lot of early history in that area, Gravity Place,” McQuillin said.

Development of Cleveland Centre started fast in the 1830s with most of the 700 lots measuring 25-by-80 feet to 25-by-100 feet and selling for from $1,000 to $2,500 each, county records show. But sales were stunted by the Panic of 1837 that endured for nearly a decade and then by the development of servicing facilities for Cleveland’s first railroad, the Cleveland, Columbus & Cincinnati (CC&C) Railroad Co., historian James Dubelko wrote in this summary.

Cleveland Centre’s real estate partnership included James S. Clarke, a former Cuyahoga County Sheriff of Cuyahoga County, insurance agent and banker Edmund Clark, plus Richard Hilliard, a wealthy dry goods merchant. Clarke was financially ruined by the Panic of 1837 but Clark and Hilliard were more diversified in their interests. They continued on with their development of the peninsula including becoming directors of the CC&C and selling 12 acres of Cleveland Centre’s land to the fledgling railroad, according to Dubelko.

In 1848, Hilliard was a charter member of The Board of Trade of the City of Cleveland, the city’s first chamber of commerce, according to the book A History of the City of Cleveland, Its Settlement, Rise and Progress, 1796-1896, by James Harrison Kennedy. In 1849, Hilliard served on the first board of trustees of the Homeopathic Hospital College, Cleveland’s second medical institution. Its first building at Prospect and Ontario streets was heavily damaged by a mob of several thousand people incited by stories of stolen bodies traced to the college’s dissecting room.

As a founder of Cleveland Centre’s original plat, Hilliard held title to a number of properties although some of the partners traded the lots amongst each other in the 1830s and 1840s, county property records show. Clarke and Hilliard owned most of the parcels that would later be consolidated into a large property that IRG would acquire. Ironically, in June 1921, a William H. R. Hilliard sold land that would eventually become IRG’s property.

At the request of NEOtrans, Dubelko researched both Hilliards but said he could not find a familial connection between the two men. Richard Hilliard lived from 1800-1856. William Hilliard (1859-1930) had his estate handled by his son T.J. Hilliard of Pittsburgh, property records show. William H.R. Williard’s father, William H. Hilliard (1838-1865), is listed in the 1850 census living with his brother Newton in what appears to be an orphanage in Painesville.

One of the oldest uses of the buildings on the site, 1786-1802 Columbus, was the Gibson & Price Iron Works, according to an 1886 Sanborn Fire Insurance Map. The firm, which made lead pipe and sheet lead using lead melting kettles and a rolling mill on site, dated to at least 1880. The Cleveland 1880 Manufacturing Census shows Gibson & Price had only six workers then, with skilled laborers paid $6 per day and $1.50 for unskilled. Gibson & Price was incorporated in 1889, Ohio Secretary of State records show. Sanborn’s 1912 map displayed the addition of a two-story building at 1776 Columbus with lead paint cans stored on the first floor and offices on the second.

This Sanborn Fire Insurance map from 1886 shows at least two of the buildings that are proposed to be demolished stood 136 years ago in the Cleveland Centre allotment and were used by the Gibson & Price Load Works. Those are just south of the railroad crossing of Columbus Road/Street. The same property was recently noted in a US EPA assessment of buildings that have had lead smelters on site (Cleveland Public Library).

A recent U.S. Environmental Protection Agency assessment of historic lead smelters included the Gibson & Price Works, 1786 Columbus. Lead is a naturally occurring but toxic metal. The assessment said the site does not qualify for the EPA Superfund’s National Priorities List for site cleanup “based on existing information.” The EPA identified the site with a “No Further Remedial Action Planned” designation.

In 1921, when William H. R. Hilliard sold the property, it was the United Lead Co. which acquired it. But they didn’t retain it for long. It was sold again, this time in 1944, to the National Lead Co. of New Jersey. Sometime after Pipe Line Development Co. was founded in 1949 but before a vending machine lease was recorded for the site in 1976, the Pipe Line Development Co. acquired the buildings at 1772-1800 Columbus. After Pipe Line Development moved in 2014 to Westlake and later to Strongsville, the property was sold again, this time to Columbus Road Foundry LLC, which also bought land across its namesake street for an indoor rowing facility.

Real estate investors have been attracted to the Columbus Road and Scranton peninsulas in the Flats due to the planned, underway or completed additions of nearby active sports, recreational facilities and parks. Those include The Foundry rowing and sailing facility; Rivergate Park’s Marina, Crooked River Skatepark and Merwin’s Wharf; Irishtown Bend, Heritage Park, Canal Basin Park, plus several new all-purpose trails like the Towpath Trail, the Cleveland Foundation Centennial Lake Link Trail and the Red Line Greenway. Both peninsulas also are the beneficiaries of a new Urban Form Overlay zoning district enacted by the city to support if not encourage higher density, walkable mixed-use developments while still being compatible with existing land uses.

On Scranton Peninsula, site preparations have started for two developments — the 300-unit Silverhills at Thunderbird apartments on the river side of Carter Road and a new production facility for Great Lakes Brewing Co. on the hill side of Carter. Meanwhile a tax-increment financing deal is pending before City Council to support NRP Group’s $100 million The Peninsula that will offer 316 apartments. Those developments will top out at five stories although the zoning allows buildings as tall as 15-16 stories, as it does on the Columbus Road Peninsula.

END