Downtown Cleveland catches the evening light on a muggy June 11, 2022, as seen from Voinovich Park and North Coast Harbor. Downtown continues to struggle to fill offices and retail spaces although hotels and especially residential buildings are performing much better since the depths of the global pandemic two years ago. Helping downtown climb out of those depths is the responsibility of many, including the Downtown Cleveland Alliance (KJP). CLICK IMAGES TO ENLARGE THEM

Like others, our downtown faces ‘uncertainty’

In the late 20th century, downtown Cleveland rolled up its sidewalks after 5 p.m. Now, on some weekdays, it seems like downtown doesn’t roll out its sidewalks until after 5 p.m. That shows how much downtown has changed in the post-pandemic world from a commercial district to a residential, entertainment and tourism center.

And it’s not just Cleveland’s urban core. Downtowns in many other cities large and small are facing challenges following the pandemic with remote work, loss of retailers and the demise of some restaurants. That challenge is now complicated by supply chain disruptions, inflation and rising interest rates. All those factors when taken together mean new office building projects natiowide are getting shelved unless one company is occupying the whole thing, as is the case with Sherwin-Williams’ new headquarters tower.

Even before the pandemic, the number of office jobs in downtown Cleveland was on a slow decline. Perhaps few people noticed because those losses were offset by a 31 percent increase in the number of residents from 2010-20. And private sector jobs grew 13.8 percent in the same period but that was offset by a decrease in public sector office jobs, according to Michael Deemer, president and CEO of the Downtown Cleveland Alliance, in an interview with NEOtrans last week.

When Deemer was a presenter on a panel discussion at the International Downtown Association’s (IDA) 2022 Annual Conference in September in Vancouver, BC, he heard from other cities facing similar post-pandemic struggles. But he also heard praise from other cities who admired Cleveland’s efforts in converting 7 million square feet of obsolete downtown office buildings into residential, hotel and mixed-use structures. In 2013, downtown Cleveland had half of Greater Cleveland’s leasable office space, or 23.7 million square feet. Today, it has just under 44 percent of the region’s office space or 16.56 million square feet, according to real estate analytics and listings firm Newmark. These adaptive reuses are why Cleveland’s downtown is doing better than some cities.

Of course, not every downtown is hurting. The site of the IDA meeting, downtown Vancouver, has less office space — 13 million square feet — than does downtown Cleveland, according to Statista.com. Yet Vancouver office spaces command nearly double Cleveland’s rents — C$51.50 or $37.50 US per square foot compared to downtown Cleveland’s $19.56 per square foot. Statista.com also reports that downtown Vancouver has a population of 60,000 people versus downtown Cleveland’s 20,000 population. Vancouver has more high-rise buildings per capita than most North American cities.

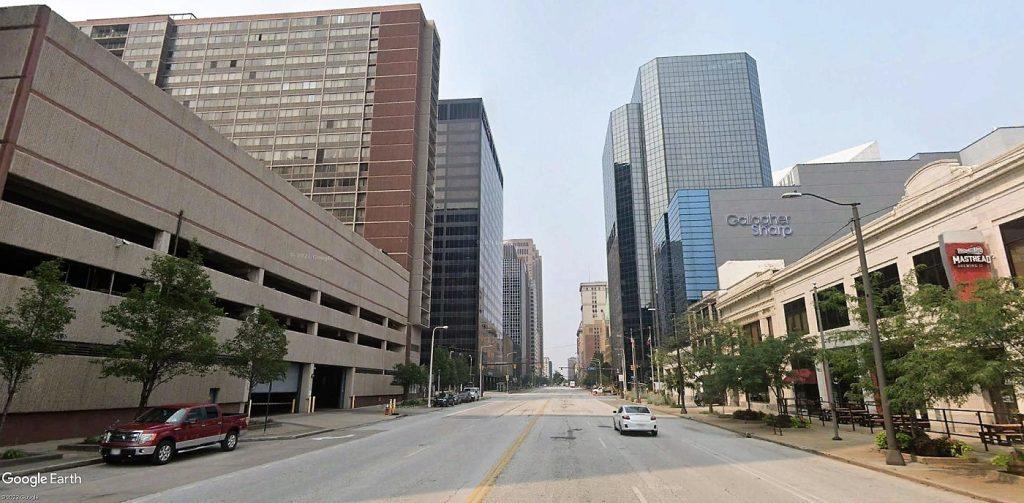

This Google Streetview image taken in July 2021 shows a part of downtown Cleveland — the office-heavy Nine-Twelve District — that hasn’t recovered from the depths of the pandemic. But most challenges offer opportunities. This empty Superior Avenue is due to be rebuilt as Superior Midway — a landscape-protected bikeway from downtown, through the Campus District, to East 55th Street (Google).

But Deemer, a self-described optimist, said he’s the first to admit that downtown faces a level of uncertainty not seen in decades. Downtown’s office workforce is 60 percent of what it was before the pandemic. Many downtown restaurants are closed for lunch on Mondays and Fridays, days when many hybrid workers are working from home. At the Greater Cleveland Regional Transit Authority’s main downtown rapid transit station at Tower City Center, ridership has collapsed on the east-west Red Line from about 2 million boardings per year prior to the pandemic to a mere 352,088 in 2021 — an 84 percent drop.

And this week, Medical Mutual of Ohio announced that it will not be bringing back its 1,000-strong headquarters workforce to downtown and will instead move them to its suburban operations center in Brooklyn. It turned downtown’s gain of CrossCountry Mortgage’s headquarters and its 1,000 employees from suburban Brecksville from a win into a draw.

Reacting to problems doesn’t produce long-term results, Deemer said. So he pointed to DCA’s Downtown Now strategic plan for the next five years. The plan was produced with the assistance of Denver-based Progressive Urban Management Associates, a real estate economics firm, which focused on how to attract more people, jobs and investment to downtown Cleveland. One of the big takeaways from that plan was to improve the experiences of people inside and out of downtown buildings, he said.

“Downtown can go either way at this point,” Deemer says. “The daytime population is slow to return. We have a relatively strong housing market and people have returned to attend sporting events and Playhouse Square shows. But we need more and the way to get that is with place-based initiatives — better streetscapes, playgrounds and things for kids to climb on, and pedestrian, biking and transit infrastructure. This is an area where Cleveland has not done a great job historically. It was an area of focus we were starting to work on in 2020. Then the pandemic hit and we went into crisis mode. We need to create more experiences downtown so that workers have to choose to be a part of it. People have more choices now.”

This past summer, DCA led the start of Lunch In The Lane — closing off a different street for the lunch hour on Thursdays and turning it into a pedestrian setting with food trucks and other vendors. DCA measured the responses by people to see if it should continue next year and in what format. One of those responses was a bit more influential than the others. Mayor Justin Bibb strongly encouraged DCA to offer more Lunch In The Lane events next year, Deemer said

Trying to fill downtown Cleveland storefronts has been difficult for decades. But during and after the pandemic, it has proven nearly impossible what with the rise of e-commerce and remote working. But four of these retail spaces in Euclid Grand development the 1000 block of Euclid Avenue are to be filled by Five Iron Golf in the coming months (KJP).

But Cleveland doesn’t disappear in the winter, so neither should its offerings of things to do. Hotels and other businesses suggested that DCA offer some cold-weather events. To that end, WinterFest is being transformed into WinterLand to encourage more families to come downtown throughout the winter — not just during the holidays. Starting the Saturday after Thanksgiving, WinterLand will continue into February.

“The idea is to animate all of downtown with lighting and music, firepits, hot chocolate stands and more,” Deemer said. “The goal is to get people out of their cars. People drive around Public Square to look at the lights and then leave without ever getting out of their cars. We’re going to switch up the lighting after the holidays and offer more programming throughout the season, including Brite Winter which is returning to the West Bank of the Flats.”

He noted that DCA wants to have a more visible unarmed presence of downtown security, which meant increasing the staff of its downtown ambassadors from 75 to 100 people. To do that, Deemer increased starting wages of the ambassadors twice over last year from $12 per hour to $14 and then to $16. The ambassadors are now fully staffed, he said, to provide security, directions to visitors, clean up trash and report other problems.

“We’re looking to add more visibility over the next year,” Deemer explained. “Next month, we’re launching with the Cleveland Police Department a deployment center at Tower City, just inside the doors from Public Square so they have a street presence and a warm interior to take a break. They’ll work on criminal issues, identify people who need shelter or are facing a mental health crisis. It’s a pilot project for Public Square and something we’re looking to expand next year.”

He also said DCA began a pilot program of safety specialists who would provide assistance to people heading from work to home, their car or to a bus or train. The specialists are available from 7 a.m. to midnight seven days a week but were available until 3:30 a.m. this past summer. He said the program was well-received and will look to improve on it next year.

Picnic tables on Mall C seldom filled with fans during the National Football League Draft April 29-May 1, 2021. What was expected to be an event jammed with people from all over the country turned out to be less than hoped. Yet it still provided downtown Cleveland hospitality businesses with customers at a time when they were desperately needed (Iryna Tkachenko).

Another piece of DCA’s strategy, he said, is to work with the city to have strong economic development initiatives in place to promote investment in more modern, amenity-rich buildings. These would improve the experiences for people inside their downtown workplaces as well as at large indoor venues such as Tower City Center where its owner Bedrock is seeking to turn it into an indoor global marketplace, Deemer said.

“Office jobs are too important to downtown and a city’s economy to ignore,” he noted. “We need to have more incentives to modernize buildings and promote more investment downtown. We’re talking with the (Bibb) administration and council on what those programs could look like.”

Ideally, he said he would like to have a five-year job creation grant program for new office jobs in the city of Cleveland, a forgivable loan program for modernizing downtown tenants’ offices plus common areas of buildings, plus a new pilot program that offers some property tax abatement for the renovation and construction of commercial properties.

“This three-pronged strategy would be a good start,” Deemer said.

Since 2005, DCA has been supported by a downtown special improvement district in which all property owners are assessed a fee. The district was renewed in 2020 during very difficult times for downtown — the depths of the global pandemic and the nationwide riots following the death of George Floyd at the hands of Minneapolis police officers. Deemer said new revenue sources are something DCA might consider, especially from development as other community development corporations enjoy.

Playhouse Square Foundation, Historic Gateway Neighborhood Corp., Historic Warehouse District Development Corp. and University Circle Inc. (UCI) are directly involved in real estate development including owning buildings, sponsoring new construction projects, owning land on which for-profit buildings are built and providing financial assistance to developments. DCA doesn’t do that which Deemer said is a philosophical decision by the DCA board to not compete with the private sector.

In 2019, the most recent year in which IRS tax filings were available, DCA earned $8.97 million in revenues, a slight increase over the year before. That same year, UCI earned $18.5 million including $6.2 million in parking revenue, $2.85 million from public safety activities, and $2.2 million in property management revenue. UCI owned $141.8 million in assets including $95 million worth of buildings, land and equipment plus $43.6 million in investments compared to DCA owning $4.67 million worth of assets, mostly cash and securitized investments.

END

Our latest Greater Cleveland development news

- Warner & Swasey conversion funding not there yet

- St. Vincent hospital demo starts; What’s next?

- Will a Brook Park stadium hurt efforts to maintain Gateway? Apparently the Cavs think so.

- Glenville, Hough, Ohio City housing wins big

- Polling data shows voters oppose Browns move

- Regional chamber of commerce likes Browns’ move