Sources say the clock is ticking on a deal with the city of Cleveland, Cuyahoga County and others on renovating Cleveland Browns Stadium, the cost of which could approach $1 billion. If there’s no deal by this time next year, the Browns could start talks with a suburban municipality for a new stadium whose price tag would likely exceed $2 billion (Google). CLICK IMAGES TO ENLARGE THEM.

City: no money for stadium renovations

Two sources, one a city of Cleveland source and the other a Cleveland Browns source, acknowledge that the clock is ticking down to a deadline that the Browns source termed as “a matter of months, certainly less than a year” for working out a deal that will keep the Browns in the city rather than turning to the suburbs for a new football stadium location. And they both acknowledge the city is offering no direct financial assistance to make major renovations to the city-owned stadium

The city source noted that Mayor Justin Bibb’s Administration does not want to see the Browns leave the city again, even if it is to the suburbs, at the end of their 30-year lease with the city after the 2028 football season. Former Browns owner Art Modell took the city’s football franchise to Baltimore after the 1995 season but the Browns’ name, colors and history remained here.

The city of Cleveland is under pressure by constituents to invest more in public safety, infrastructure, housing and other neighborhood quality-of-life issues and to share the cost burden of a rebuilt Browns stadium with more of Northeast Ohio’s political jurisdictions. A recent Scene Magazine article noted that only 15 percent of Browns game attendees reside in the city of Cleveland and only 31 percent live in Cuyahoga County. A real estate insider who may become involved in a Browns move to the suburbs wondered what would be the loss to the city if the team built a stadium in the suburbs for 10 home games a year plus other major events like concerts, conventions or visiting college sporting events.

“The city could instead spend money on fighting crime and improving services and infrastructure,” said the insider. “Considering how few city of Cleveland residents attend Browns games, letting the Browns go to the suburbs might actually improve Bibb’s re-election chances.”

But the Browns source countered that losing the team again would be an emotional issue for Cleveland residents and a loss of prestige for the city, regardless of any positive fiscal impact on the city. The source said it would be a black eye for Cleveland, even though 12 of 32 National Football League teams already play their home games in suburban municipalities. That number is expected to grow soon to 13 when the Chicago Bears move from downtown to Arlington Heights. Several other teams play within the city limits of their metro area’s “mother city” but not downtown, such as the Tampa Bay Buccaneers, Philadelphia Eagles and Green Bay Packers.

“Talks between the city and Browns organization continue,” said city of Cleveland Press Secretary Marie Zickefoose. “We have no further updates at this time.”

“We’re still researching all of this,” said City Council President Blaine Griffin. “The (Bibb) Administration has not sent any proposals to council yet.”

Peter John-Baptiste, senior vice president of communications for team owner Haslam Sports Group and the Cleveland Browns, did not respond to a e-mail from NEOtrans.

“There is going to be a public-private partnership and getting that right is not easy,” said Browns owner Jimmy Haslam in July. “We do have experience from having done it down in Columbus. We did it quickly but that was not easy during COVID. The only thing (wife) Dee and I would say for sure is we’re not leaving Northeast Ohio. That’s for sure. Our preference is for us to be on the lakefront. But we’ve got to see how things play out. It will be fluid. There will be bumps in the road and it may be different in three months than it is now.”

Ironically, while Browns ownership Jimmy and Dee Haslam pointed to the city of Columbus for an example of a productive partnership regarding stadium investment, the city of Columbus also provided no direct financial investment into building the $313.9 million, 20,000-seat Lower.com Field, home of the Haslams’ Columbus Crew Major League Soccer team. That stadium opened in 2021 just west of downtown Columbus as part of an overall real estate development called Astor Park, developed by the Haslams. The Haslams are capturing revenue from up to 270,000 square feet of commercial and office space along with new luxury and affordable housing to help finance the stadium.

A similar approach is desired by the city of Cleveland — funding development around Cleveland Browns Stadium and capturing revenues from that development for stadium renovations. In Columbus, private funding of Lower.com Field amounted to $217.5 million with another $20 million from the state, $25 million from a state-funded loan and $51.3 million in bonds paid for by Franklin County. The city of Columbus’ share amounted to $63 million for developing the mixed-use Astor Park development and pledged another $50 million to turn the Crew’s previous stadium site into the team’s training center and a community sports park.

The Browns’ training center is in the Cleveland suburb of Berea and the subject of potential redevelopment and expansion in that suburb. So the city of Cleveland reportedly views its own potential direct financial contribution to a renovated stadium as limited to the stadium-area development. The city on Aug. 25 filed articles of incorporation with the Ohio Secretary of State’s office for a North Coast Waterfront Development Corp. and registered North Coast Development Corp. as a tradename of the new company under which it would do business.

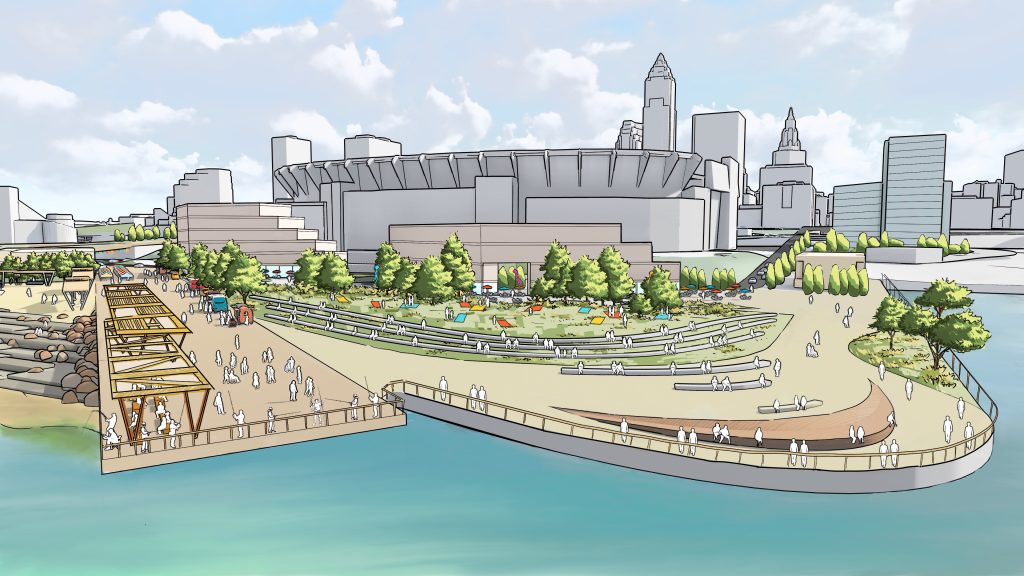

The new company was created by the city as a nonprofit charitable organization for purposes of “organizing and executing on the equitable development of the Cleveland lakefront as a destination for residents, business, and recreation,” according to its articles of incorporation. The city intends to use this corporation to capture revenues from lakefront development and secure government grants plus private donations to fund public infrastructure near the lakefront — whether the Browns’ stadium is nearby or not.

In late July, the city of Cleveland revealed its vision for redeveloping the lakefront with many recreational uses and few residential or commercial uses that would produce revenues for rebuilding the stadium. The stadium was included in the plan but as a largely featureless box, like a player to be named later in a trade among teams. A key feature of the plan is a $200+ million land bridge from downtown, over the lakefront railroad tracks and possibly the Shoreway, that would extend the park-like downtown malls to the water’s edge.

“The lakefront was seen as a place for rich, white folks,” said Mayor Bibb. “This (lakefront) plan wasn’t formed in a board room. It was formed with input of the people who would use it. Cleveland is one of the most segregated cities in the country. The river and the lake were part of that as dividing lines. We’re proposing a lakefront that is a place of healing.”

Cost of renovating the 67,431-seat stadium when the Browns’ lease with the city ends after the 2028 season could reach nearly $1 billion, or half the cost of building a new, comparably sized, open-air stadium, according to real estate sources. Adding a fixed roof could cost upwards of $2.5 million and a retractable roof at least $3.5 billion. The team source said the Browns wanted a new stadium on the northeast side of downtown but the cost and lack of city support for it doomed the idea.

Real estate insiders said two potential suburban stadium locations could meet the Browns’ needs by offering a mostly vacant, 100-plus-acre site with as few different owners as possible, that’s close to Interstate highways and accessible to public transit, possibly by extending rail transit to it. One is on the east side — the 330-acre Highland Hills Golf Course in Highland Hills owned by the city of Cleveland between Harvard Road, Chagrin Boulevard, Northfield Road and South Green Road. The other is on the west side — a 175-acre site in Brook Park owned by a three-company joint venture called DROF BP I LLC (“Ford” backwards, “BP” for Brook Park) which was the Ford Motor Co.’s engine and casting plants at Snow and Engle roads.

END