It may look like a new building but it’s not. As part of Cleveland State University’s desire to add more dorms, the 1971-built Rhodes Tower may be converted to housing and get a new exterior. This is just one example of how it could look. Another is to add glass curtain walls to protect the precast concrete façade from moisture and better insulate the building (CSU). CLICK IMAGES TO ENLARGE THEM

There’s more to the plan than meets the eye

When Cleveland State University (CSU) formally released its downtown campus master plan to the public last week, a few things were left out. Their exclusion wasn’t because of some devious intent to deceive the public. Rather, it was because CSU officials and those at the Boston-based planning firm Sasaki Associates CSU hired to develop the master plan hadn’t yet made decisions on the omitted elements.

There is one element to the master plan that was omitted and NEOtrans isn’t sure of the reason why. That omission is an extra digit in the price tag for realizing this ambitious master plan at a time of high construction costs — i.e.: a digit placed to the left of a newly added comma. CSU and Sasaki officials said the cost of building out the master plan, as proposed, would be about $650 million.

NEOtrans spoke to several local real estate and construction industry insiders about that cost estimate and got a variety of responses, but almost all of them began the same way — an expression of disbelief. Some said that $650,000,000 figure should be doubled. Others said it should be tripled. Either way, we’re talking a sizable distance north of $1 billion, or $1,000,000,000.

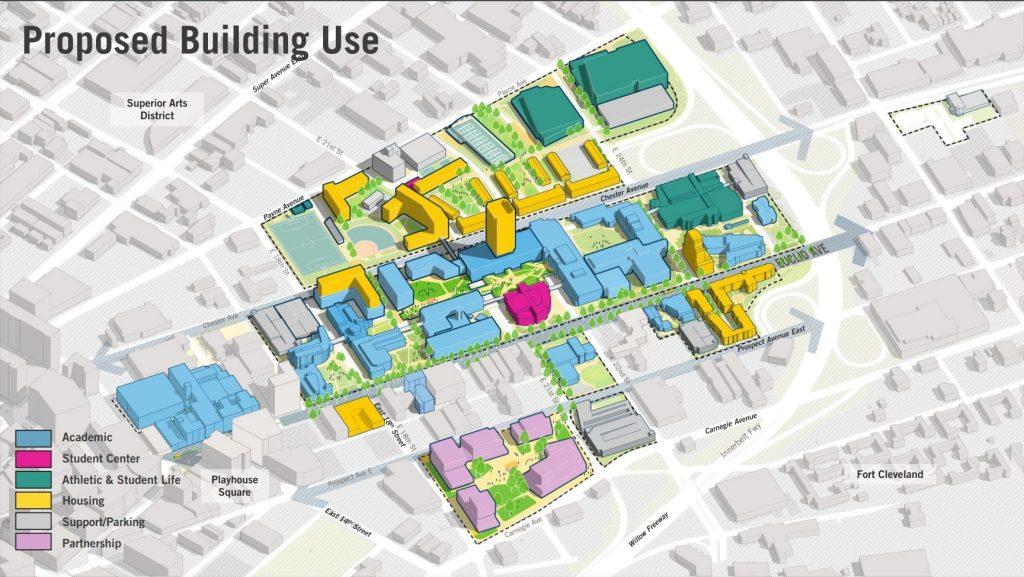

The reason? Let’s start with the probable cost of a new arena. There are two new college arenas in the USA that are of a similar scale to what CSU proposes — a 5,000- to 7,000-seat arena between Chester and Payne avenues, providing a commanding presence over Interstate 90 in downtown Cleveland’s Campus District. One new, comparable arena is just starting construction. The other just finished construction.

Opening this fall was Arizona State University’s new 5,000-seat Mullett Arena in Tempe. It cost $136 million — a price tag that kept going up as it was being built to reflect the rising costs of construction. Also out west, Baylor University in Waco, TX started construction last summer on the $185 million Foster Pavilion. The 7,000-seat all-purpose facility will replace the larger, 10,400-seat Ferrell Center. The 34-year-old Ferrell Center will be demolished for future development.

While the size of CSU’s new arena hasn’t been decided, the situation at Baylor is familiar. Baylor has an enrollment (about 14,000) similar to CSU’s Fall 2022 total (14,579). Like Baylor, CSU is also seeking to get out of a larger arena and into a smaller arena. CSU’s 13,610-seat, 1991-built Wolstein Center is slightly larger and newer than Ferrell Center, but by the time CSU is ready to raze Wolstein Center, it may be as old or older. Demolishing a facility of Wolstein Center’s size won’t be cheap, either. Consider that the cost to demolish the 20,000-seat Joe Louis Arena in Detroit two years ago was $12 million.

And, like Baylor, CSU proposes to redevelop the 10-acre site where Wolstein Center now stands. Providing a 10-acre development site in a downtown setting should be a boon for development. But will it? There are already 11 acres of surface parking lots west of the Wolstein Center, east of the Gateway Sports & Entertainment Complex, north of the Central Interchange and south of Bolivar Road/Prospect Avenue that have sat underutilized for decades.

Granted, not all of the owners of these properties want to develop them. Others have tried and haven’t succeeded for various reasons, including their own shortcomings. And a few others have the wherewithal to pull off their intriguing development plans that are in the works. Still, 11 acres is a lot of under-developed land. Nearly doubling it by opening up the Wolstein Center site would expand a surplus of developable land. A bright side is that a surplus may lower land prices to the point that properties start to change hands to those seeking a return on a costly development investment.

The fate of all this land depends on what CSU has in mind for the Wolstein Center site. In looking at the university’s new master plan, it’s not clear what that is. The site is called by the plan as “The Partnership District” but precious little is said about it. Proposed is “nearly 800,000 square feet of mixed-use development designed to drive economic development in the area and connect partners to the university.” That 800,000 square feet of space would cost about $300 million to build at current construction costs. Who knows how much that cost will rise to in five-plus years after a new arena is designed and built and the old Wolstein Center is razed.

David Jewell, CSU’s senior vice president of business affairs and chief financial officer, said The Partnership District will provide a clean slate for anyone and everyone to suggest some ideas on what to do with it. Jewell names city, county, education, corporate and health care partners to offer their thoughts on what to build on what he calls “10 acres of prime, downtown real estate next to a major RTA (Greater Cleveland Regional Transit Authority) hub and a parking garage.”

Two underutilized facilities sitting side-by-side on state-owned land for Cleveland State University. At right is the Wolstein Center arena which has never sold out in its 31-year history, according to CSU data. At left is the Greater Cleveland Regional Transit Authority’s 12-year-old Stephanie Tubbs Jones Transit Center which is used as the endpoint of only one surviving bus route out of many that once served it (Google).

CSU’s South Garage, 2101 E. 21st St., has 611 parking spaces and is an important facility. The RTA hub isn’t anymore. The Stephanie Tubbs Jones Transportation Center (STJ) was a busy place when it first opened in 2010 at a cost of $9.6 million, mostly from federal stimulus funds. In the early 2010s, RTA carried nearly 50 million riders per year. Multiple bus routes converged here, including those of the growing intercity operator Megabus.

Now the only route still serving it is the No. 55, called the Cleveland State Line by sponsorship from CSU, to the West Shore suburbs. Today, the only people getting on and off buses at the STJ are the drivers to use the facility’s bathroom. Last year, RTA had just 15.9 million riders. The 1.3-acre site of the STJ is a sizeable piece of urban land owned by CSU and should be repurposed from a dormant transit center to something more useful. Yet it was not mentioned in CSU’s master plan as a developable site within The Partnership District.

One possible use for the partnership district would be to greatly expand its medical school and research facilities and programs. In recent years, CSU seemed like it was on a fast track to become a bigger and better medical and health innovation university to support the expansion of the Cleveland Clinic, University Hospitals and MetroHealth systems, plus the region’s growing biotechnology scene. CSU had joined with Northeast Ohio Medical University (NEOMED) to create the NEOMED-CSU Partnership for Urban Health, which has its physical presence in the 2015-built, $48 million Center for Innovations in Medical Professions Building at the southwest corner of Euclid Avenue and East 22nd Street.

Then, in 2020, CSU hired Rocky River native Forrest Faison III, former U.S. Navy Vice Admiral and served as the 38th Surgeon General, as its senior vice president for research and innovation/chief healthcare strategy officer. Faison was to oversee a broad effort to unify and expand the university’s educational, outreach and scholarship efforts in all aspects of health care, while spurring the continued growth of Cleveland as a center for medical innovation.

Unfortunately, those goals have yet to be achieved. Faison left after less than two years on the job. Then-CSU President Harlan Sands, who hired Faison, left in April in a less-than-amicable separation. CSU still hopes to boost its research, medical and technology transfer programs with the resultant workforce housed in its future Partnership District.

“The possible collaborations and benefits to the university and the community are only limited by our imagination,” Jewell said in a press release.

Aside from the Wolstein Center’s demolition and a new arena overlooking Interstate 90, one of the biggest changes is the activation of Chester Avenue. Several significant new residential buildings are planned here including a vertically stacked residential-academic facility across from Krenzler Field (CSU/Sasaki).

In other words, CSU doesn’t appear to have a definitive plan with end-users in mind for the Wolstein Center site, assuming it is demolished. In 2014, the last time CSU updated its campus master plan, it also proposed demolishing the Wolstein Center. But that master plan wasn’t clear on where a new arena should be built. One suggestion was to build a new but smaller arena on the same site, possibly surrounding it with student housing.

Instead, the site for the new arena is on CSU-owned land next to the Superior Arts District. That neighboring district is being acquired by a new Cleveland development partnership called TurnDev financed by a new capitalization partnership called TurnCap. It is comprised of several local heavy hitters including CrossCountry Mortgage CEO Ron Leonhardt Jr. whose mortgage firm is moving its headquarters and 600 jobs from Brecksville to Superior Avenue at East 22nd Street. On Nov. 23, the partnership completed a chain-of-title property transfer via the city of Cleveland to create a tax-increment financing district for 5.4 acres of land. That site, bounded by East 21st and 22nd streets, Superior and Payne avenues, is for CrossCountry’s new headquarters and apartments in six connected, historic buildings comprising a $100 million redevelopment.

As TurnCap/TurnDev continues to acquire and develop this district with corporate offices and multi-family residential, it’s going to need structured parking. CSU is also going to need structured parking for the new arena. But does each need to be build their own parking decks for daytime office users and evening/weekend arena visitors? Probably not, which is why the development partnership and CSU have discussed jointly constructing shared parking facilities along Payne. The absence of any arena parking structure in the master plan suggests that no deal has been reached yet on this joint effort.

Just south of the Superior Arts District, CSU’s master plan aims to reactivate Chester with multiple new structures, including a large, vertically stacked residential-over-academic structure across Chester from Krenzler Field. Despite the ambitions in the master plan, this soccer/lacross field appears to be left pretty much untouched. One wonders why, with CSU soccer drawing capacity crowds and a new effort to bring professional outdoor soccer to Cleveland. However, options for expanding Krenzler are limited. One option might be to shift Krenzler and Viking (softball) fields to the east by about 50 feet each to avail space for bleachers along East 18th Street. That would shrink the footprint for proposed housing along the west side of East 21st from about 3.5 acres to 3.2 acres.

The first piece of CSU’s master plan to show up on the landscape will likely be the proposed $21 million Corporate Connector building. Serving as a workforce development center, the five-story building could see construction by the end of next year in the 2300 block of Euclid Avenue, developing a pretty but unused greenspace in front of the to-be renovated Science Research Center. The Corporate Connector won’t be the last new academic building added. The master plan shows a roughly four- to five-story academic building built on another pointless patch of urban grass at the northwest corner of Euclid and East 21st but offers no timeline for it.

A conceptual rendering of new housing planned between Chester Avenue at right and Payne Avenue at left, with East 21st Street just beyond the proposed nine-story dorm. Viking Field is visible as is a portion of Krenzler Field at the bottom. CSU’s master plan offers no significant changes to either Krenzler or Viking fields. A pedestrian walkway over Chester is shown linking the new dorms to the academic core including Rhodes Tower converted to housing (CSU/Sasaki).

Last but certainly not least is campus housing. If CSU is going to rekindle its pre-pandemic growth, attract more international students and continue to transition from predominantly a commuter school to one with a vibrant residential campus, it needs a lot more housing than the four residence halls it has. NEOtrans was first to report more than a year ago that CSU was seeking to acquire the Langston Apartments on Chester and The Edge on Euclid Avenue that doubled its dorm building count from two to four.

Combined, those two added complexes contain 1,164 beds. They were already used by students but because they were privately owned, CSU couldn’t market them as part of its scholarship offerings and in its meal/housing plans, especially to international students. Previously, CSU had only two on-campus housing properties — the Euclid Commons with 601 beds and the 22-story Fenn Tower with 438 beds.

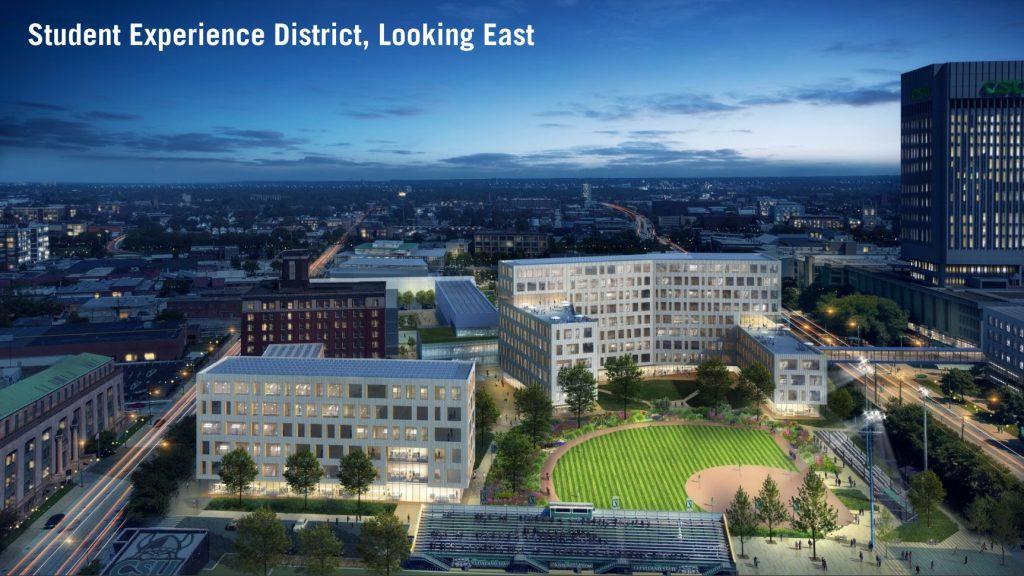

That’s still not enough and CSU knows it. In 2017, prior to the pandemic, CSU admitted its first-ever freshman class with 2,000-plus students. Overall enrollment has dipped since with smaller families and the rising cost of college. International enrollment also fell until this year when it made a “significant” jump, according to CSU officials. If CSU is going to grow, it needs international students to achieve it. That means more on-campus residence halls. CSU is proposing to add another 1,000 beds in at least two new large dorms north of Chester at East 21st in an area called the Student Residential Experience District.

But CSU’s tallest dorm won’t involve new construction. CSU plans to convert the partially vacant Rhodes Tower, the fourth-tallest educational-purposed building in the USA at 363 feet. The 21-story tower has the same floor count as CSU’s shorter and older Fenn Tower, also a student dorm. Above the five-floor podium, the 52-year-old Rhodes will be converted to dorms offering roughly 400 beds and be thoroughly renovated inside and out. Its exterior, built with precast concrete walls, offers little insulation from cold winds or protection from moisture and must be addressed.

According to sources familiar with the university’s plans, the tower’s exterior will be re-clad which will make it look like a new tower in the skyline. But that won’t be cheap regardless of whether the exterior is replaced or if it is covered by a glass curtain wall system. Either way, CSU will enjoy improved energy efficiency and related operational cost savings from the tower’s new exterior that could help finance renovation costs likely to exceed $100 million, according to some industry insiders.

Despite the imposing price tags of some of these items in CSU’s master plan, they must be done if CSU is going to take an even larger role in energizing Cleveland’s urban core. One only needs to look nearby at the economic impact of Ohio State University (2022 total enrollment of 65,795), University of Michigan (51,225) or University of Pittsburgh (28,234) on an urban setting. And while CSU is unlikely to grow as large as them, even a 35 percent rate of growth over the next decade, from 14,579 students to near 20,000 enrollment would attract more retailers, restaurants, hotels, conferences, innovative companies and employment growth that benefit students and non-students alike.

END

Our latest Greater Cleveland development news

- Michael Symon joins River Roots’ move to Flats

- Tenant ID’d for big new industrial development near Hopkins airport

- $119M Lakewood Common project goes vertical

- CWRU to renovate, expand one of its most historic buildings

- Master Chrome coming down, cleaning up

- Familiar Ohio City buildings go on sale for the first time in 143 years