Downtown is a canvas for Cavs, Browns, Guardians

All three major league sports teams in Cleveland have real estate development plans for downtown Cleveland. They are some of the grandest visions that have been put out there. And while some of those plans have been made public, most remain a secret because they’re still in the process of refining those plans. Some details are unknown because they depend on the resolution of significant infrastructure investments.

The reason for each plan is, of course, money. But it’s not just money that’s being sought for the pockets of each team’s billionaire owners. The money from each team’s real estate developments will also help to offset and reduce the amount of public financing to be sought for a new or improved stadium, arena and ballpark.

But suffice it to say — if each plan is implemented as it appears they could, these real estate developments would dramatically alter the face of downtown Cleveland, especially from the Cavaliers’ and Browns’ plans for the city’s two waterfronts. And there was news on both of those waterfront plans in this past week.

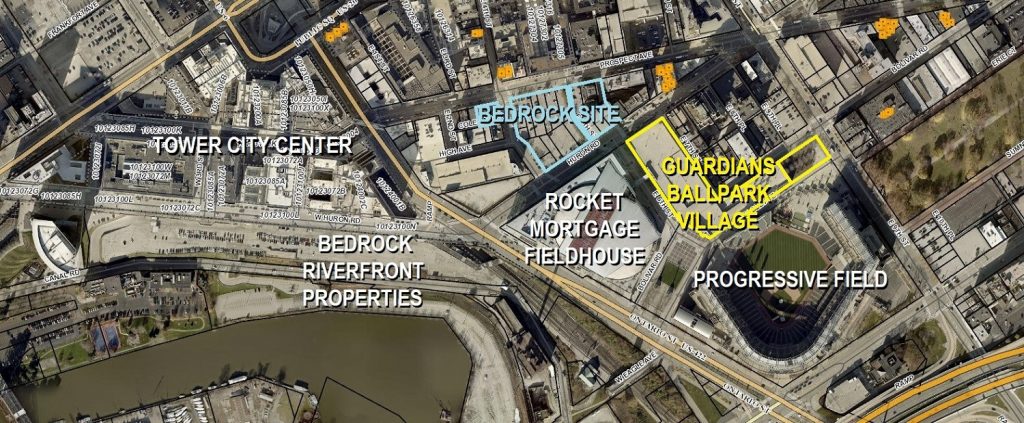

A rough sketch of a portion of Bedrock Real Estate’s riverfront plans between Huron Road and the Cuyahoga River. Bedrock was founded by Dan Gilbert, owner of the of the Cleveland Cavaliers who play at Rocket Mortgage FieldHouse, seen at right. All of the owners of Cleveland’s sports teams are planning real estate developments next to their sporting venues (DCA).

Cleveland Cavaliers–Dan Gilbert

Earlier this week, NEOtrans reported on news that Detroit-based Bedrock Real Estate has a purchase agreement to acquire Sherwin-Williams’ (SHW) soon-to-be-vacated Breen Technology Center, 601 Canal Rd. Bedrock was founded by Dan Gilbert, majority owner of the Cleveland Cavaliers basketball team. It plays at Rocket Mortgage FieldHouse, a 1994-built arena across Ontario Street from the Cuyahoga River valley.

SHW is relocating its research and development activities to suburban Brecksville at the end of 2024. Sources familiar with the pending transaction say Bedrock would demolish the research facilities and further open up land along the Cuyahoga River to achieve its portion of the city of Cleveland’s Vision for the Valley.

Bedrock’s pending purchase of 9 acres of SHW-owned land would add to the real estate firm’s 20 acres of riverfront land used primarily as surface parking lots. This is the closest riverfront to downtown’s Public Square and to the Cavs’ arena, yet is largely undeveloped. Gilbert wants to change that, and has changed Bedrock’s leadership to help make it happen. He hired Bedrock CEO Kofi Bonner, plus Christopher Noble, senior vice president of commercial real estate development and Deb Janik, senior vice president of business development.

For a Detroit company, the Cleveland connections are ubiquitous. Bonner is a former Cleveland Browns executive. Noble is a former chief of development at two Cleveland-based firms — Forest City Enterprises, previous owners of Tower City Center, and Stark Enterprises which is reportedly selling its nuCLEus properties in the Gateway District to Bedrock. Prior to January, Janik worked for 17 years as senior vice president, business growth and development services at the Greater Cleveland Partnership.

While Cleveland’s other sports teams appear to be investing in real estate to support new or renovated sports venues, the Cavs’ owner isn’t — at least not in the near term. Gilbert interest in real estate shouldn’t be a surprise. It’s nothing new — he practically owns half of downtown Detroit. In fact his primary source of wealth has been in mortgage companies including Quicken Loans, the nation’s largest mortgage lender. His internet-based Rocket Mortgage is growing fast and has a significant office presence in downtown Cleveland; its lease at the Higbee Building is due to run out Dec. 31, 2026.

With more than 1,400 jobs locally, look for Rocket Mortgage to be a major tenant in whatever and wherever Bedrock builds. Law firm Benesch was also considered. Now that Benesch is moving to Key Tower, look for Bedrock to zero in on another growing office tenants and headquarters to add to its downtown tenant mix.

A potential candidate may be steelmaker-shipping giant Cleveland-Cliffs which has a longstanding partnership with Gilbert’s Cavs that only grew more visible in the past week. Cliffs has been rumored to be in the market for a new HQ site despite investing in improved offices for its CEO Lourenco Goncalves at 200 Public Square.

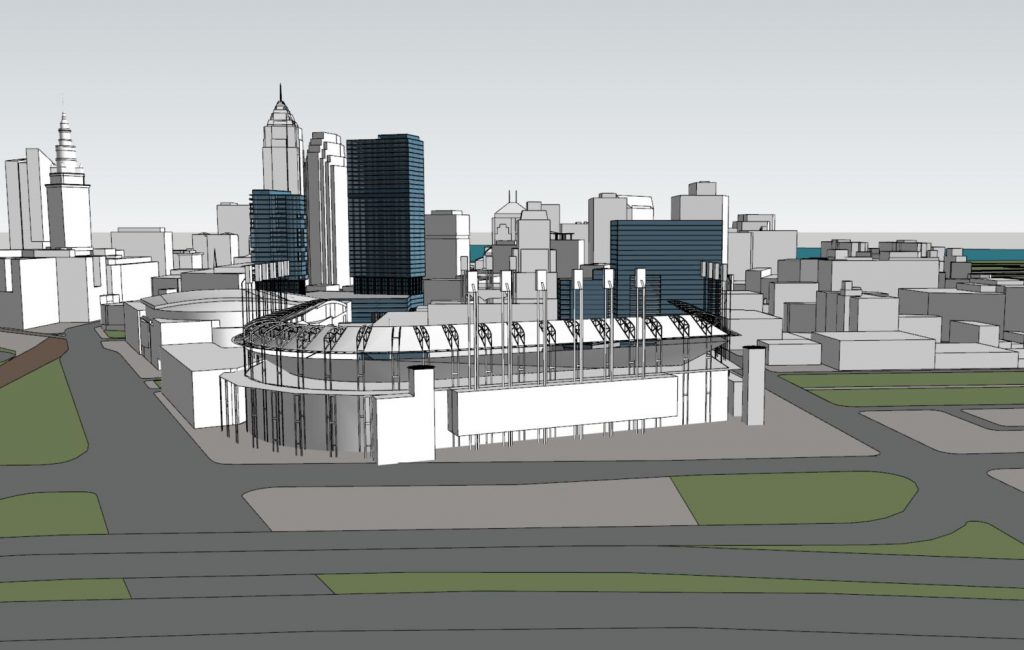

Rocket Mortgage FieldHouse underwent $185 million in renovations in 2019. It should be in good shape for a while, but could use further renovations or a possible replacement in another decade or two, which is the approximate timeline that Bedrock sketched out for achieving its grand riverfront development vision last fall.

But real estate industry sources are giving mixed messages on whether that’s truly the case. Some say Bedrock’s plans for realizing its riverfront dreams could be achieved sooner. They point to Bedrock’s pending deal with Sherwin-Williams for the Breen property, its creation of a new real estate entity called Huron Holdings to which the Tower City parking lot between Huron and Canal roads was transferred last December, and its reported plans to rebuild its parking garage below Tower City Center.

But Gilbert is facing an 18-month timeline (from November 2021) just to determine infrastructure costs and to finalize a development agreement with the city. It will be years more before streets and riverside infrastructure can be altered. That’s why others say Gilbert’s first new-construction investment will instead occur up the hill in the heart of the Gateway District, on 2.85 acres of land currently owned by Stark Enterprises. Several sources say Bedrock is buying that land, a claim denied by Ezra Stark, chief operating officer of Stark Enterprises.

In December, Stark directed its law firm Thompson Hine LLP to get certificates of disclosure from the city’s building and housing department for all of its Gateway properties that have structures on them. Stark said the certificates had nothing to do with a pending sale. Normally, certificates of disclosure are secured as part of research into properties that are subject to a sale and transfer to a new owner.

When asked about the accuracy of reports that Bedrock was seeking to buy the Stark properties, Lora Brand at Bedrock’s PR firm Falls & Co. gave the same answer she gave to NEOtrans when asked about the pending sale of the Breen Technology Center to Bedrock. “If Bedrock has any news on any developments to share, we will let you know,” she said.

NEOtrans also received information that CBRE was hired to handle Bedrock’s commercial leasing for its Cleveland developments. When NEOtrans sent an e-mail to Keith Brandt, managing director of CBRE’s Cleveland office, to confirm or deny the accuracy of that information, he immediately opened the e-mail but did not answer it.

One year ago, sources said Bedrock extended an agreement to retain Cleveland architectural firm Vocon to conduct programming for a new mixed-use development. Bedrock also hired design and engineering firm IBI Group of Toronto to provide construction and engineering services, but limited the work to geotechnical and environmental analyses of Bedrock’s riverfront properties. IBI Group staff was to start collecting soil samples from Bedrock’s riverfront properties next to Tower City Center a year ago but that work never happened, sources said.

While the information is confusing and contradictory as to where Bedrock will strike first with its first new-construction development in downtown Cleveland, there is one thing that the sources agree on — it will be big. Some say it will be as big as Bedrock’s Hudson’s Site in downtown Detroit. That’s a $1 billion, 1.4-million-square-foot development whose tower will peak at 48 stories and 685 feet when construction is done next year. Like Detroit’s, Cleveland’s will reportedly mix retail, parking, housing, hotel and office uses in the same structure.

Equally intriguing is that Gilbert’s real estate dreams for Cleveland are reportedly being pursued in coordination with the Cavs’ neighbors in the Gateway Sports and Entertainment complex. Why? Because they pretty much have to.

Cleveland Guardians–HBSE

Yes, the Dolan Family led here by Paul Dolan is the current majority owner of the Cleveland Guardians, nee Indians. But that’s probably not going to be the case in a few years. According to published reports, David Blitzer and Josh Harris are near to acquiring for about $400 million a 35 percent ownership stake in the Guardians that would also put them on a path to acquire a majority stake from the Dolans in 2026.

Blitzer and Harris are a couple of East Coast billionaires who are partners in Harris-Blitzer Sports & Entertainment (HBSE). Multiple sources close to Gilbert’s Bedrock Real Estate and to HBSE say the two groups are coordinating their efforts to deliver a mixed-use complex that activates on a year-round-basis more economic benefits from the sport facilities.

Why does HBSE want to get involved in real estate in Cleveland? For two reasons — that’s what they do in cities where they have majority ownership stakes in sports teams — Philadelphia 76ers basketball, the New Jersey Devils hockey plus their minor league teams, the Delaware Blue Coats basketball and the Binghamton Devils hockey. Second, Major League Baseball is encourage team owners to create ballpark villages around stadiums to diversify revenue sources and provide value-capture financing for stadium improvements and replacements.

A significant attraction to HBSE is the recently approved $435 million renovation package for Progressive Field and a 15-year lease extension for the Guardians that started Jan. 1. There are also two five-year extensions. The city and county agreed to financially support Progressive Field’s renovations and the Gateway Economic Development Corp. of Greater Cleveland extended the Guardians’ lease. Another element in the lease agreement proved attractive as well.

Per that agreement, for the next two years the city of Cleveland will make the Gateway East Garage, 650 Huron Rd., and its 3.3 acres of land available for the Guardians to purchase for $25 million. In the event the team purchases the Gateway East Garage, the city will use the sale proceeds to fund the city’s annual $2 million commitment towards the Public’s Ballpark Contributions and shall assign future naming rights sale proceeds to the team.

Furthermore, the lease extension agreement says Gateway agrees to convey or cause to be conveyed the half-acre Gateway Development Parcel at East 9th Street and Bolivar Road to the team in exchange for a $2 million purchase price. Gateway or its transferee will then convey its entire share of the sale proceeds into the Ballpark Improvement Fund.

Combined, a 3.8-acre plot of land in the heart of a major-city downtown and next to major-league sports facilities is a large canvas for future development. Demolishing some or all of the 1,650-space Gateway East Garage means another parking garage will have to take up the slack for it during demolition and construction of a ballpark village that may or may not include a redesigned parking garage as part of it.

That’s where the partnership with Bedrock would come into play. Sources say construction of a large parking garage will be part of whatever Bedrock has in mind for its Gateway and/or riverfront developments. The added parking would support not only Bedrock’s developments but also a proposed ballpark village and the sporting and entertainment events at Rocket Mortgage FieldHouse and Progressive Field.

What might the ballpark village look like? Sources pointed to St. Louis and its ballpark village for a possible glimpse. It features year-round food and entertainment venues, hotel and a high-rise apartment building. All of those things could be accommodated on the 3.8-acre plot of land to the north of Progressive Field.

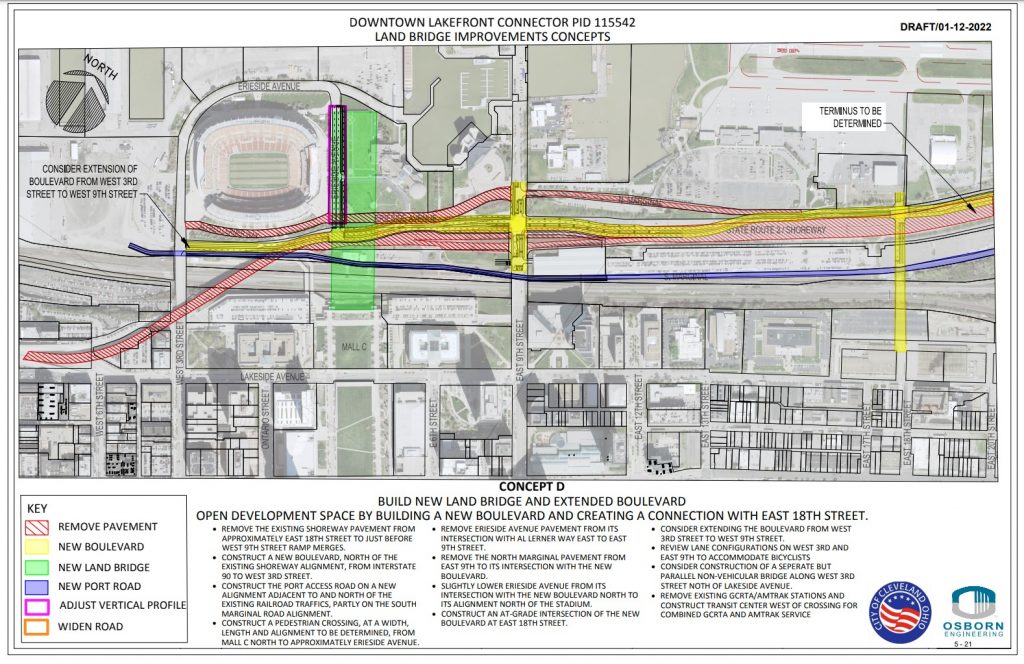

A key to developing the lakefront is to create more seamless pedestrian linkages between downtown and the water’s edge. That means constructing this $230 million land bridge that descends gently from the downtown malls, over the railroad tracks and lands next to North Coast Harbor. But since the Shoreway is elevated and rising to the west here, the highway is in the way of this progress (AoDK).

Cleveland Browns–Haslam family

For the first time, the owners of the Cleveland Browns are starting to talk openly about a new stadium for the football team and possibly for other large events such as concerts, professional soccer games and more. And, like their basketball and baseball counterparts, having new, large steady revenue streams coming in from developed lakefront real estate to retire bonds would be preferable to what Buffalo just did in asking the public to pay $850 million for its new $1.4 billion football stadium.

Cleveland has a football-only stadium on its underutilized lakefront because, when Art Modell took his football team to Baltimore in 1995, Cleveland Mayor Mike White said he wanted a new Browns team playing before the end of the century. That meant there was only place where a modern football stadium could be built so quickly — where the old municipal stadium stood. All of the water and sewer infrastructure for a 70,000-plus-seat stadium was already there.

The new stadium opened in time for the Browns to return to the field in 1999. But not everyone was happy. Many civic leaders, from Mayor White’s Planning Director Hunter Morrison to Gateway Sports and Entertainment Corp. Executive Director Tom Chema during the arena’s and ballpark’s early-1990s construction, were disappointed that such a large, lightly used football stadium was returned to the lakefront to take up so much space.

For the Browns, their stadium lease with the city will expire at the end of 2028. By then, the stadium will be 30 years old and one of the oldest in the National Football League. That alone isn’t a reason to replace it, even though FirstEnergy Stadium does need more than a new coat of paint since its $120 million update in 2014.

Whether the Haslams and Greater Cleveland can afford a new football stadium will depend on many things. One of those things is the fate of the Shoreway highway past the existing lakefront stadium. The reason is that a proposed land bridge over the railroad tracks to connect downtown and the lakefront needs the elevated Shoreway removed or lowered.

This design alternative, called Concept D, proposes constructing a landbridge across the railroad tracks, removing the Shoreway downtown, constructing a port access road, combining Amtrak and light-rail services in a new station, building a new boulevard and extending East 18th Street north to the new boulevard to ease traffic and develop the Campus District (Osborne).

A study now underway by the Ohio Department of Transportation (ODOT) to determine traffic impacts from several options of redesigning the Shoreway or replacing it with a boulevard through downtown will determine whether funding from ODOT and the Federal Highway Administration can be used and, if so, which pots of money.

If traffic is slowed down through downtown, traditional ODOT and federal dollars can’t be used. However, there are new pots of ODOT and federal funds for transportation projects whose goals aren’t for putting more cars through cities at higher speeds. They include ODOT’s Jobs & Commerce Economic Development (JCED) program and the new federal Reconnecting Communities pilot program (Sec. 11509) for removing highways and viaducts that divide cities.

If the Shoreway isn’t removed, the lakefront will remain severed from downtown and a less extensive redevelopment of the downtown lakefront will only be possible. Under that scenario, a limited amount of revenues from a lakefront development can be generated for the football stadium. That means the lakefront stadium will probably remain where it is, albeit renovated.

But if the Shoreway is replaced with a boulevard, it could allow the restoration of a street grid and pedestrian connections across buried railroad and transit tracks, creating a unified downtown community from the central business district to the water’s edge. More residents, workers, offices, shops and recreation can be added. Under that scenario, more lease and tax revenues could be generated to afford removing the existing football stadium and building a new one someplace else.

Two relocation options appear under consideration, according to real estate industry sources. One is the Plan B site from the 1990s that was widely favored by almost everyone except the mayor — the former intermodal rail yards. Located on the other side of Interstate 90 from the Gateway complex, the site would be easily accessible by highways and all rapid transit lines which share the same tracks below the site. The property is owned by ODOT, thus potentially reducing site acquisition costs. The transaction could even be used as ODOT’s share of converting the Shoreway into a boulevard.

The former intermodal yards site on the south side of Interstate 90 from Progressive Field (top-center) could accommodate a football facility the size of FirstEnergy Stadium with room left over for a plaza (shown in green), two parking decks (in black) and a rapid transit station (in red) near downtown Cleveland (KJP/Google).

But the site is constrained from offering much spin-off development. The nearest potential development area is the Flats South District but is mostly on the other side of I-90. Another possibility might be the redevelopment of some or all of the 35-acre main post office property which doesn’t need as much space as it once did. But considering how seldom a football stadium is used, perhaps spin-off development isn’t as important unless it can be it own attraction as is the Patriot Place lifestyle center in Foxborough, MA.

The other site alternative reportedly in the conversation is the northeast side of downtown, north of St. Clair Avenue and in the East 20s. While this would give the Haslams the ability to develop around a new football stadium and expand downtown along Davenport Bluffs, there are more than 100 small properties that would have to be acquired.

The site would be accessible from I-90, a proposed new East 18th Street extension to/from the Shoreway and bolster the Campus District’s call for extending the light-rail Waterfront Line as a loop via the east side of downtown to also serve Cleveland State University, Tri-C Metro and the growing St. Vincent Hospital. But absent land use regulations and an emphasis on use of the existing Muny Parking lots along the Shoreway, it also risks turning the area between downtown and Asiatown into a sea of surface parking lots. Of course, that assumes the Browns go the new-stadium route.

“The city and the (Greater) Cleveland Partnership have taken over the waterfront development piece, and we have committees working on that,” said Dee Haslam in a written statement. “Our part now is how we bring the stadium up to a better standard, so I think we’ve started interviewing and thinking about architects and consultants. We’re kind of in that very beginning stage and can start having those conversations, and hopefully marry it with the work that the city and partnerships are doing on the waterfront development.”

Timing

While the All-Star Game in Cleveland in mid-February seemed like an opportune occasion for Gilbert to announce his big surprise, it was not to be. The last of the certificates of disclosure were gathered for the Gateway properties only one month earlier. When Sherwin-Williams gathered the certificates for its new headquarters west of Public Square, three more months passed before it made its HQ site selection official.

It often takes a year for the buyer of a major property acquisition to go through its due diligence, including geotechnical analysis. However, Stark already gathered geotechnical data for the Gateway properties prior to making construction-ready plans for the shorter nuCLEus. Bedrock was about to conduct similar core drilling for the riverfront properties but told its geotech firm to stand down in April 2021. If a purchase agreement for Stark’s properties was the reason, then one would think an announcement from Bedrock is coming soon.

The Guardians’ plans would follow Bedrock’s, if for no other reason that a major new parking facility will need to be provided first before the Guardians acquire from the city the Gateway East Garage for possible demolition. Purchasing the parking garage and the development parcel at East 9th and Bolivar would need to occur sometime in the next two years, per the new lease with Gateway. The garage’s partial or full demolition would follow to create a ballpark village development site.

The Browns’ decision making depends on the outcome of a federally compliant project development process for redesigning or downgrading the Shoreway as a boulevard. Some answers from that process should come by the end of this year when a locally preferred alternative for a transportation investment is chosen. The Browns will be in a position to decide whether it may pursue a stadium renovation or a new stadium — and where.

Then detailed design and engineering of the transportation improvements for the chosen alternative will be carried out in the following two years along with funding procurement. Assuming all of the construction funding for the Shoreway redesign/removal can be found in a timely manner, shovels could start turning dirt for it as early as 2026 — three years before the Browns’ stadium lease runs out.

END

- Haslam email preempts City, County at stadium debate

- NE Ohio projects get historic wins from tax credits

- Haslams announce Brook Park stadium-area development partner, updated plans

- Old Brooklyn structures OK’d for demolition

- Shoreway Tower has construction in view for 2025

- North Collinwood ‘historic’ modular townhomes OK’d

Comments are closed.