A Greater Cleveland Regional Transit Authority Blue Line train coasts into the Warrensville Station in Shaker Heights at the east end of the line where the $100 million first phase of the Van Aken District was under construction in 2018. Phase two is now under way and will deliver two high-rise apartments just one block away (AAO). CLICK IMAGES TO ENLARGE THEM

Transit-oriented development effort gets under way

A new initiative has started that, if successful, could reverse decades of urban sprawl, a hollowing out of Greater Cleveland’s urban core and an erosion of its transit system. It would also address a wide variety of problems that hurt the region’s environment, safety, economy and human health. The new initiative would accomplish that by encouraging more accessible, pedestrian-friendly, mixed-use developments along high-frequency transit corridors in Cleveland and Cuyahoga County.

The Cuyahoga County Planning Commission, Cleveland City Planning Commission and the Greater Cleveland Regional Transit Authority (GCRTA) are leading an effort to support a return to how cities were designed for 5,000 years — a more pedestrian-oriented approach that the private and public sectors have already begun in piecemeal fashion. But most development that is pedestrian-oriented is also transit-oriented development, or TOD. If you’ve traveled around town in the last couple of years, you’ve probably seen examples of it. TOD includes a dense mix of commercial, residential, office and entertainment centered around or located near a transit station in a walkable setting.

A large-scale example is the INTRO development in Cleveland’s Ohio City neighborhood that could soon gain a second phase featuring a high-rise of up to 16 stories. Or, the Van Aken District in Shaker Heights whose second phase started last week featuring two high rises of 18- and 15 stories. A medium-sized TOD is Woodhill Station West in the Buckeye-Woodhill neighborhood that could see its second phase starting next year. There are many smaller-scale TOD-thematic developments such as Mayfield Station in Cleveland’s Little Italy, Aspen Place in the Detroit-Shoreway neighborhood, or the Northeast Ohio Regional Sewer District (NEORSD) headquarters on Euclid Avenue in MidTown.

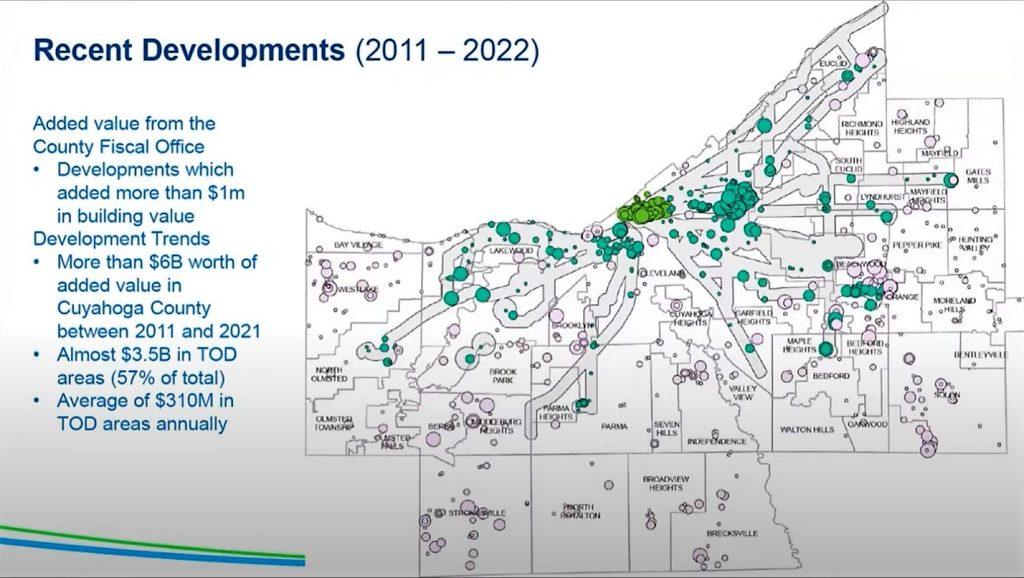

Shown here are circles representing real estate investments of more than $1 million in value occurring 2011-22. The larger the circle, the larger the investment. The bright-green circles are investments in downtown Cleveland that are accessible by frequent transit from multiple directions. The teal-colored circles are investments within the walkshed of high-frequency transit corridors. The pink circles are not accessible by frequent transit (CCPC).

As individually impressive as each project is, collectively they don’t tip the scale in favor of filling the doughnut hole that is left behind the wake of continuing urban-sprawl in a metro area that barely grew in population between 2010-2020. That exacerbates the worsening physical disconnect between jobs and job seekers, where in Greater Cleveland only 10 percent of available jobs are within a one-way, hour-long transit commute, according to the Cleveland Federal Reserve Bank. It creates car over-dependency that worsens human health with more air and noise pollution, sedentary lifestyles and more car crashes. And it imposes a more expensive transportation system especially for the poor who often spend as much or more on getting around than on housing.

A working group of 26 communities and associated agencies has been established to remove policy barriers to TOD and advance public sector incentives for it, said Mary Cierebiej, executive director of the Cuyahoga County Planning Commission during a TOD presentation last week at the Cleveland City Planning Commission. Now that the county, city and GCRTA have presented reports looking at TOD successes and how land is currently used along high-frequency bus and rail routes, they will now start looking at zoning to allow transit-supportive land uses near bus and train stops.

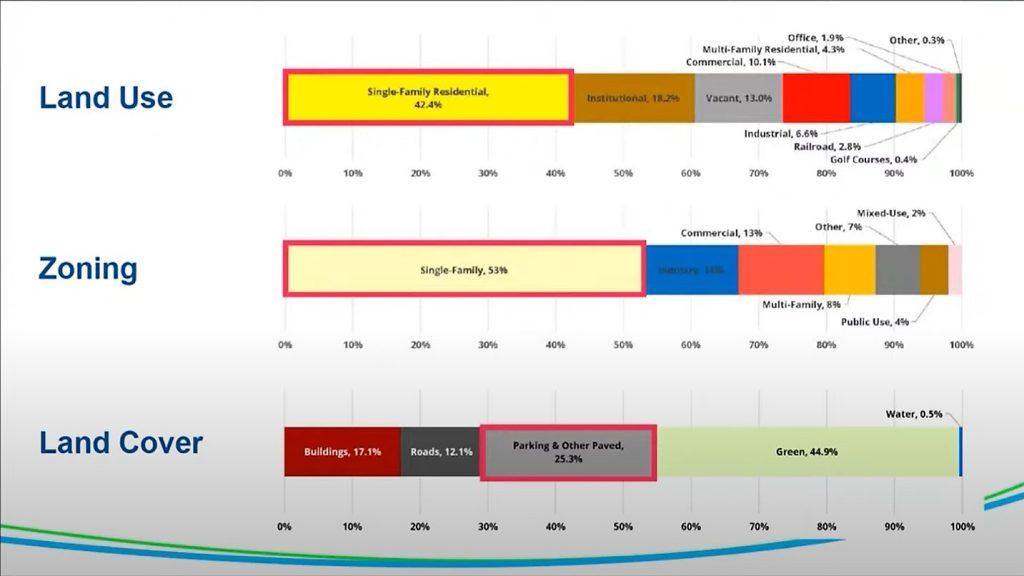

“We will be doing educational sessions in the coming weeks about our zoning analysis” of land along those high-frequency transit routes which comprises 19 percent of all land in Cuyahoga County, said Patrick Hewitt, planning manager strategy and development at the county’s planning commission. “There remains significant opportunities to add density and development along TOD corridors. More area is being used for parking than buildings in the corridors where we’ve invested in frequent and rapid transit.”

Numerous developments have popped up around GCRTA’s Little Italy-University Circle station since it opened in 2015. That includes the aptly named Mayfield Station Apartments, at right, that were still under construction in 2019. This building had to get a variance from the city to offer fewer parking spaces than the zoning code allows, even though it is steps away from a train station (KJP).

Consider that, within a quarter-mile “walkshed” of bus routes offering daytime departures every 15 minutes or better and within a half-mile walkshed of rail stations, only 17 percent of land in those areas is used for buildings; 25 percent is used for parking, according to a new report by the Cuyahoga County Planning Commission. And buildings — especially when designed with mixed uses and placed next to sidewalks — generate walking and transit use, Hewitt said. Another 45 percent of land is devoted to greenspace and 12 percent of land use near transit stops was identified as roads.

“We know, as we’ve been looking, just because there is investment doesn’t mean it is TOD,” Hewitt cautioned. “The design of new development heavily influences whether something conforms to the principals of TOD. That can go quite a bit with the zoning that communities have.”

Cleveland City Planning Manager Matt Moss said that Cleveland’s zoning makes most transit-supportive land uses illegal. In a new TOD report, he zeroed in on the city’s Detroit-Shoreway neighborhood for an example. Despite significant development since 2015 that added more than 1,200 housing units to this stable west-side neighborhood and that has 86 percent of its land area within a five-minute walk of a stop on a high-frequency bus and rail transit route, it still falls well short of being transit-supportive. He cited Federal Transit Administration data which considers a density of 25-35 housing units per acre as supportive of high-frequency transit. Cleveland uses 30 units per acres as its threshold.

This chart shows how land is used and zoned within the walksheds of high-frequency bus and rail transit corridors in Cuyahoga County. The land use, zoning and land cover is not transit-supportive and would need to be changed if the region wants to support its decades-long multi-billion-dollar investments in high-frequency bus and rail transit with ridership-productive land uses (CCPC).

“To achieve 30 units per acre, the (Detroit-Shoreway) area needs 24,476 housing units, or an addition of 18,314 more units within the (transit) walkshed to become transit supportive,” Moss said. “But in most of Detroit-Shoreway, as it is in most of the city, it is illegal to build more than three units of housing (per parcel). The city’s nascent form-based (zoning) code has a lot of features that can allow TOD to be built.”

He said that strategies for increasing density include adopting the form-based code, developing affordable housing and district parking on city-owned land, plus working with community development corporations and city council to engage property owners to promote TOD sites. Moss also said CDCs and council members need to engage existing residents on the benefits of TOD and a shift from auto dependency, tracking data on projects and units being delivered to the market to support forecasting and planning neighborhood development policies.

GCRTA officials note that two of Ohio’s four largest job hubs — downtown Cleveland and University Circle — are on multiple high-frequency transit corridors. But if more than two trips a day — to and from work — on transit is desired, then land use and transit needs to be better integrated to create a 15-minute city. That concept has grown in importance with remote work. A 15-minute city is actually the presence of numerous nodes within the larger city where human needs and desires are accessible within a 15-minute walk, bike ride or transit trip. The key to making that happen is to bring more housing as well as more retail, educational facilities, basic services and medical care to within a short walk of high-frequency transit routes.

“Some of our policies don’t support these goals, including zoning,” Moss said. “We have choked off the housing supply along our transit corridors. Permitting more housing units along these corridors is a necessary step to building a more transit-oriented city.”

City Planning Commission Chair Lillian Kuri said she welcomed the TOD initiative by the county, city and GCRTA but wanted to see an analysis of where public-sector job-creation incentives are being focused geographically. She said there’s a big misalignment between how the state, county and cities incentivize people to locate their businesses away from transit yet those businesses often have a difficult time attracting people to apply for their jobs.

The reason is a large labor pool is isolated from most available jobs. One-fourth of all Cleveland households have no car available whereas 10-20 percent of households in inner-ring suburbs are lacking cars, Census data shows. And many more households share just one car among more than one wage earner, according to All Aboard Ohio, a rail and transit advocacy association.

“There’s no correlation between either the size of that (job-creation) subsidy and the location along transit corridors or trunk lines, if you will, where we (the city) might control land,” Kuri said. “We need to think more about an alignment of the (incentive) tool kit. I want to see us say, somehow, that if you locate your business on a major trunk line of transit, that there are more incentives for you to do that.”

END

- Cleveland, Bedrock seek $1 billion for riverfront development

- CRE industry lauds Bibb’s construction permit overhaul

- Bridgeworks design evolves again – minus hotel

- Cleveland Kitchen wins $10M in tax credits

- Welleon gets an ‘A’ in testing Cleveland’s market

- EPA gives Greater Cleveland $129.4M for five solar arrays, reforestation